My memories of Ramkinkar Baij, such as they are, are interlaced with two things that one rarely associates with an artist. The first, curiously, is kerosene. And the second, somewhat less oddly, is summer, or rather, a hot summer day.

One afternoon in the middle of April, in 1973, my friend and I were walking around Santiniketan’s quiet Ratan Pally on some errand, when my friend nudged me and pointed at someone who was coming from the opposite direction. He was a bare-bodied, bare-footed man in a short dhoti and a wide straw topi, and slung from his right arm by a piece of rope was a green bottle that smelt strongly of kerosene as he passed by us.

I gasped as my friend told me who he was, for only the previous day I had seen some of the Ramkinkar sculptures that dot the Santiniketan landscape. The only other time I saw him was in late May or early June of 1975, when another friend and I, on a rickshaw from the Bolpur station to Santiniketan, caught a glimpse of Ramkinkar on a bicycle, the bottle of what I thought was kerosene slung from the bike’s handlebar this time. It was a murderously hot day, but Ramkinkar seemed to me to be in perfect harmony with his surroundings, much as his sculptures had always appeared to do with theirs.

The truth, though, is that Santiniketan had always treated Ramkinkar as a bit of an oddball. Here was a true bohemian who set little store by convention, whether in his art or in his life, and genteel Santiniketan found it hard to come to terms with him. Indeed, it is a safe guess that, had Rabindranath Tagore not been alive when Ramkinkar first came to Santiniketan, he would have found the place far less welcoming. Great artist and peerless teacher that he was, Nandalal Bose was yet a traditionalist, and here was a student who not only had begun to work in oil since his early teens but also appeared to have evolved an idiom of his own already.

Extraordinarily talented people seldom fit smoothly into rigorously formal training systems, as Rabindranath had known from personal experience, and, but for the poet’s active encouragement, Ramkinkar would probably have found himself at a loose end early on.

‘Sujata’ (1935) – one of Ramkinkar’s earliest forays into alfresco sculpting. Photo: Biswarup Ganguly, CC BY 3.0/Wikimedia Commons

A callow 19-year-old from rural Bankura, Ramkinkar had arrived in Santiniketan in 1925, quite fortuitously. But since he had been recommended as a student of Santiniketan’s Kala Bhavan (the Art school) by Ramananda Chatterjee, the legendary editor of both The Modern Review and the Prabasi (‘The Expatriate’) magazines, Rabindranath himself kept an eye on the artistic development of this great idiosyncratic talent.

Also read: Cutting Through Mountains to Build a Statue

Ramkinkar pretty much sailed through Kala Bhavan’s academic programme and later joined the same school’s teaching faculty, becoming, in a few years’ time, the chair of the department of sculpture. He had grown up watching the local craftsmen and image-makers of Bankura at work, learning how to make small clay figures with the same felicity as drawing and painting with whatever resources that came his way. And now, with his intellectual horizons widened immeasurably and his artistic imagination allowed full play, he turned his attention to out-of-doors sculpture, something virtually unknown in India outside of religious and colonial-heritage installations dedicated to gods or rulers.

One of his early works was a representation of the Buddha, of course, but the themes he readily engaged with nearly always revolved around ordinary people living their quotidian lives in unremarkable circumstances, their daily struggles, joys and sorrows, disappointments and triumphs.

Indeed, his 1935 sculpture ‘Sujata’ was also conceived as only a portrait of a Kala Bhavan student, though the later addition, at Nandalal’s instance, of an above-the-head receptacle – presumably containing a devotional offering of payasam – transformed the portrait into one of the famous Buddha disciple’s. What is extraordinary about this early work, though, is that it was visualised not only as a work of art in and by itself: it was executed as verily a part of a eucalyptus grove inside the Santiniketan campus where the depicted human figure seemed to blend seamlessly with the slender tree-trunks crowding around it.

Rabindranath must have liked it greatly, because he is understood to have suggested to the young artist that he ‘fill the campus with sculptures’. If Ramkinkar needed any encouragement to press ahead with his alfresco projects, here it was.

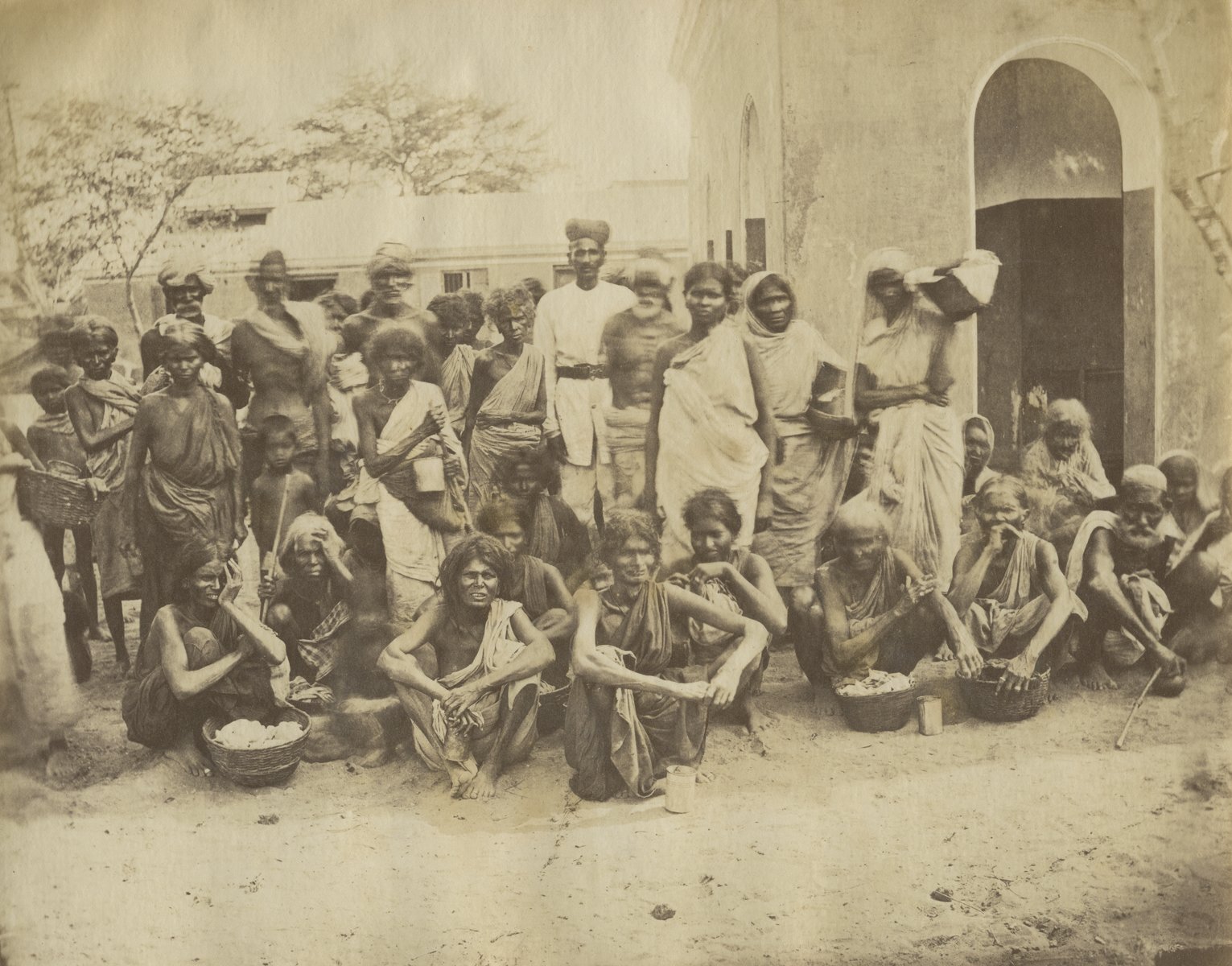

In turning determinedly away from mythological or religious subjects, Ramkinkar inevitably focussed on the community of Santhals inhabiting the villages around Santiniketan. Here was a community which had managed to preserve the integrity of its pre-modern lifestyle, though it was increasingly getting exposed to an industrial – or, at any rate, an industrialising – society. Ramkinkar once spelt out his admiration for the community with characteristic candour:

(If) I feel an attraction towards them, the main reason behind this is their life, (its) vigour and rhythm. Their movement and words are rhythmic. The same rhythmic quality is reflected in their households, their day-to-day activities. Their lives are not as coarse and dirty as our lives.

It is this ‘vigour and rhythm’, this conflation of easy grace and strong simplicity, that many of Ramkinkar’s sculptures so majestically capture. Two monumental creations – Santhal Family (1938) and Mill Call (1956) – stand out.

(From the left) Santhal Family and Mill Call. Photo: Wikipedia

Santhal Family (detail) Photo: Wikipedia

These are studies of human beings in motion – moving house with their meagre belongings in one case, and rushing to answer the call of the factory siren in the other. Acute observation, compassion, humour and a touch of pathos shape these creations, but the overriding sense is one of verve and sparkle, of grace and strength.

The idiom is uniquely Ramkinkar’s: it effortlessly melds modern western and pre-classical Indian sculptural values in equal measure. Of course, he had scarcely any option other than to strike out on his own, because there had been no significant Indian sculptural tradition before him – except the popular ones of memorial/religious sculptures – that he could have drawn upon with profit. And since he brought the first truly modern sensibility to Indian sculpture while still being firmly rooted in the soil he grew up on, he emerged as the first authentic exponent of modern Indian sculpture.

But while works like Santhal Family and Mill Call are invested with a strong lyrical content, Ramkinkar was equally adept in evoking a sense of wretchedness or stark hopelessness. The headless female nude in Thresher is captured in the act of harvesting corn – a potentially life-giving ritual whose purpose contrasts tellingly with the dreariness of the effort itself. The crippling human cost of the Bengal Famine of 1943 is adumbrated in this work. After all, hundreds of thousands of Bengal’s poor perished in that catastrophe – among them countless peasants who put food on privileged tables but starved to death themselves.

Also read: Man, Artist, Wound: Somnath Hore as I Knew Him

Few of Ramkinkar’s public sculptures were commissioned or sponsored work – except the Yaksha/Yakshi duo installed at the entrance to the Reserve Bank of India in New Delhi – and he had to make do with whatever resources he could mobilise locally through his personal efforts. This must have obliged him to use only inexpensive, locally available material, but his genius helped metamorphose this seeming handicap into an abiding strength.

Many of his sculptures were crafted with cement concrete – rather than stone or bronze or plaster of Paris, all expensive ingredients – combined with laterite pebbles, abundant quantities of which were available in and around Santiniketan then. His chosen medium gives his alfresco sculptures their distinctive texture and flavour. They look as though they have risen out of the ground, much like termite mounds seen growing out of Santinketan’s red soil. They are rugged, earthy, zestful – never unexciting or flat.

Ramkinkar built each sculpture around metal armatures – or bamboo-and-stick contraptions perhaps held together by a piece of rope – and threw clumps of the cement-laterite paste over them, which he shaped and chiselled away at as he went along. It was an extraordinarily demanding effort, for cement, unlike clay or plaster or wax, hardens quickly and is difficult to handle. And yet he fashioned out of this material numerous busts and portraits, often at incredible speed.

The Poet (1937). Photo: NGMA Delhi

Ramkinkar’s sculptures – much like his paintings – defy pigeonholing into a particular category: modernist, expressionist, cubist or abstract. He absorbed multiple influences, often many at the same time, and assimilated them so completely as to be able to fuse different approaches and styles effortlessly, often in the same work. Expressionism remains a strong undercurrent in his work, but his portraits and busts also reflect an abstraction of form accentuated by somewhat distorted anatomies, highlighting the essential characteristics that define the person being depicted.

The 1937 image of Rabindranath Tagore (see above) is an outstanding example. The poet’s face is profoundly unlike its habitual image, and yet the narrow head with a significantly elongated nose, the penetrating eyes, the receding hair that curls inwards and a beard that pleats well beyond the chins together leave the viewer in no doubt about the subject or the power of his presence. This is perhaps one of the first post-cubist character portraits done by an Indian sculptor.

‘Famine’ (1943) Photo: National Gallery of Modern Art

The minimalist creation Famine, on the other hand, reproduces with a fine weave of expressionism and symbolism the horror of the Bengal Famine. Bulging eyes on a bloated head perched on top of an emaciated body and spindly fingers clasping at an empty begging bowl create an image that haunts the viewer well after she is done viewing.

I had begun by recalling my personal memories of Ramkinkar Baij. Let me end with two glimpses of what posterity, in India, has chosen to do to his legacy. In December 2015, on a day trip to Balaton from Budapest, I made what I then thought was a startling discovery but later realised was stale news. Balaton is central Europe’s largest freshwater lake and a splendid all-season tourist destination, but to me, an Indian, it recommended itself on another count – its association with Rabindranath Tagore. In a heart sanatorium in the charming lakeside town of Balatonfured, the poet had spent three weeks in October 1926, convalescing. He had been taken ill in course of a long and gruelling tour of Europe that covered Scandinavia to Italy to Hungary.

The rooms of the hospital the poet stayed in have been preserved as a memorial to Rabindranath, and there is a lovely ‘Tagore Promenade’ on the lake-front made up of two rows of linden trees, the first of those trees having been planted by the poet himself, as a tribute to Balaton, after he got back his health.

The Tagore bust that offended genteel sensibilities. Photo: National Gallery of Modern Art

I loved the place, but wondered why a very ordinary-looking Tagore bust had been placed in the middle of the promenade. Oddly, the bust sat on a pedestal that seemed to lean a little to the front. I forgot all about it, however, till I reached the sanatorium/museum when I found, sitting on a desk inside the room the poet had occupied, Ramkinkar’s magnificent 1940 study of Rabindranath.

It is a remarkable study, for it is the image of a pensive old man whose deeply-lined brow bears witness to tragedy and pain, not an image exuding Olympian equanimity. Why was this masterpiece lying cooped up in a room even as a perfect mediocrity stood outside in full public view, claiming to represent India’s greatest poet?

It turns out that it was, indeed, the Ramkinkar bust that had first adorned the promenade, and a slightly tilted pedestal had been chosen to accommodate its unusual bearing. However, sundry Indian VIPs (mainly politicians but also, sadly, some well-known Tagore aficionados) clamoured in later years for its banishment, averring that it was ugly, and by no means an ‘authentic’ image of the sage-like poet.

The controversy raged for many years before it finally smoothed the way, in 2005, for the non-descript academic sculpture to make its appearance, relegating a wonderful work of art to the obscurity of a closed room. I, an Indian, had to hang my head in shame in far-away Hungary that day.

Cut to Ramkinkar’s own Santiniketan, where, in January 2017, my wife and I were visiting after many years. One afternoon we were walking around the Kala Bhavan complex, trying to figure out how much the whole place had changed since we had been there last. It was then that our eyes fell upon an extraordinary scene: a portrait of Ramkinkar in a rubbish dump. The bust looked suspiciously like the copy of a famous study by a reputed artist, but that was hardly the most striking thing here.

Ramkinkar bust in a rubbish dump in Santiniketan. Photo: Author provided

What really stood out was the supreme unconcern with which Santiniketan had come to treat the memory of arguably its greatest plastic artist, a titan who, in his time, had spurned fame and lucre so that he could go on living, and working, in peace in the place he had made his home.

No question that India was well on its way to becoming the Vishwa Guru.

Anjan Basu can be reached at basuanjan52@gmail.com