The noted filmmaker, Mrinal Sen, reminded me of my ‘second-hand’ experience of a tragic episode in Bengal’s history. It was the early 1980s and I, along with a friend, was on my maiden interview which at that point I did not know would initiate me into a lifetime in journalism. At the end of our conversation on his cinema, when conversation turned to the personal, Sen learnt I was a probashi Bengali.

His words of advice turned into a continuous lesson – “try understanding Bengal’s three traumas and you will know more about your sub-conscious – Bengal partition, Bengal famine and turbulent Bengal of 1960s and 1970s or events following from the peasants’ uprising in Naxalbari.”

Since then, I never tired reading about these episodes and every time a ‘conclusion’ was reached, a new perspective would be discovered.

With time, as I discovered passion for history – a subject our school forced us to turn away from for offering only the science stream after middle school – I felt Sen would have made me wiser if he had added a fourth episode – the Battle of Plassey. I am sure readers would have their own takes and may suggest other essentials to better comprehend Bengali sub-national consciousness and identity. Other sub-nationalities too may look into their histories to bookmark watersheds from the past, specific to their states or regions.

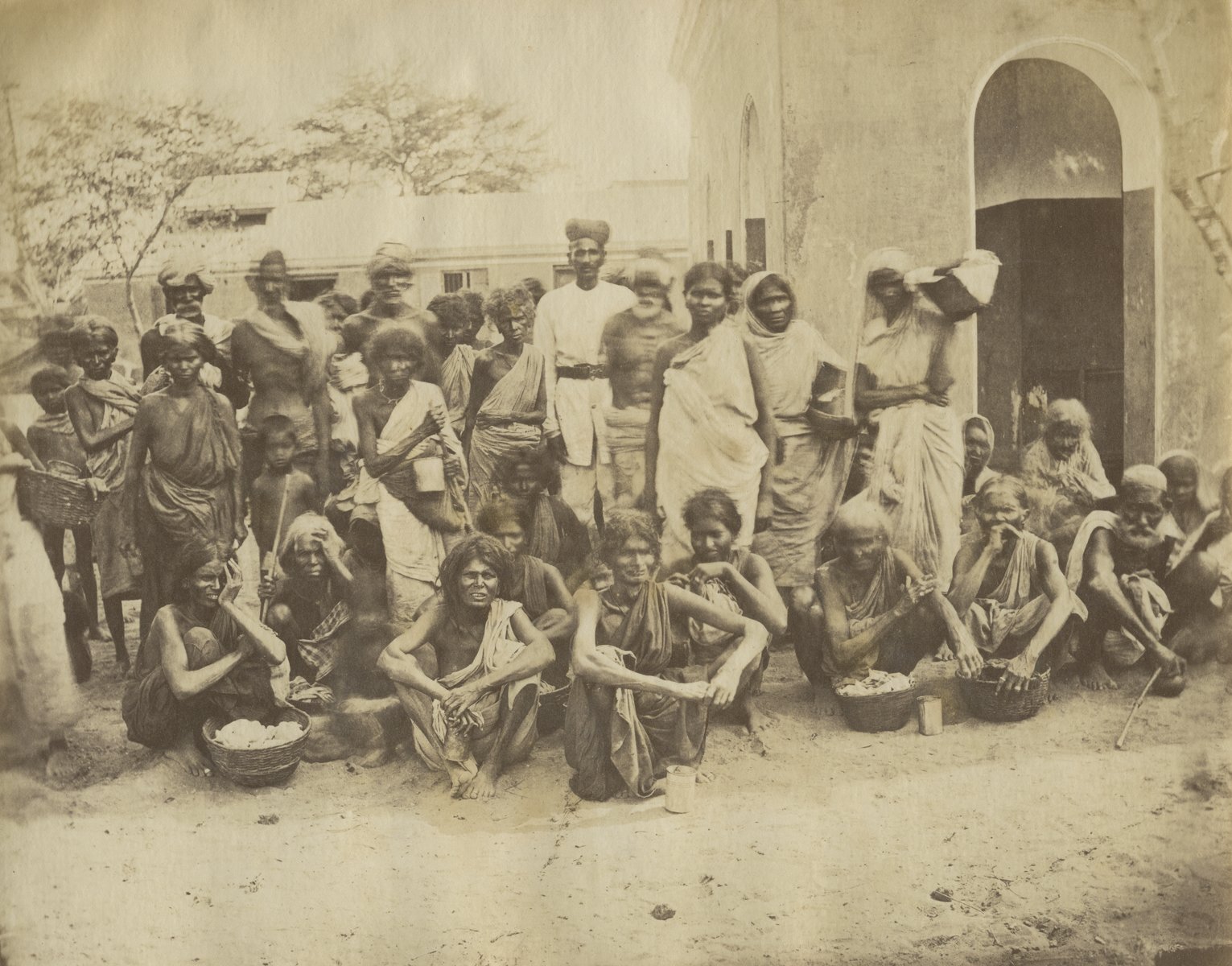

Although the Bengal famine wrought havoc on people of the province for three years beginning 1942, it is most commonly referred as the Bengal famine of 1943. This year then marks 75 years since the tragedy that killed an estimated three million people. The second-hand experience which I mentioned previously, stemmed from my father being a young boy at that time.

Although he was privileged enough to avoid being part of the hordes that thronged – bowl in hand, to government grain shops much before these opened, at an early age he learnt what scarcity was. My father’s privileges, however, were lesser than the other Sen who gets mentioned in this piece – the economist with the first name of Amartya, and the one who stood with cigarette tins filled with rice to hand over to the hungry when they lined past his grandfather’s house. But my father’s tales and lessons inculcated the lifetime habit of not wasting food, especially cereals or ann as they say in Hindi.

It is not that he unilaterally decided one day that it was time to ‘educate’ his only born. Instead, the question regarding this was posed by me when I returned one summer from a sojourn at grandparents’ in Varanasi. On a rare brawl I picked up during the visit with a neighbouring boy, I was called to shut up because I was a bhooka Bangali. Because my grandfather was rather non-communicative when I reported the incident, I waited to ask my father.

He explained that possibly the slur had its origins in the famine – he provided in-depth account of this – when famished and skeletonous people fled Bengal in thousand. “Naturally, they were hungry,” he said and also detailed how the Indian People’s Theatre Association, with which he was associated briefly, had choreographed the famous musical composition – Bhooka Hai Bangal which found mention even when the government issued a commemorative postage stamp to mark IPTA’s golden jubilee. “Some people possibly still use the phrase as abuse because it remains in their collective memory just as this conversation will be remembered by you,” my father explained although using much simpler words and sans jargon.

Amartya Sen received his Nobel prize mainly on the strength of his work on famines and the book Poverty and Famines, which had a chapter on the ‘Great Bengal Famine’, began with the following premise:

“Starvation is the characteristic of some people not having enough food to eat. It is not the characteristic of there being not enough food to eat. While the latter can be a cause of the former, it is but one of many possible causes. Whether and how starvation relates to food supply is a matter for factual investigation.”

In several other papers, essays and books he reiterated that a majority of famines do not have cause and effect relationship with reduced availability of food due to drought and floods. Sen’s argument to the contrary, was that famines occur despite food being adequately available and because there is disbalance in the consumption pattern. More food, he argued, was available to one section – for a variety of reasons – and the other group is literally starved of supplies.

If the hypothesis is true, then it should be possible to prevent famines. Or even reverse these by a series of steps which could include seizing traders’ excess stocks, limiting supply to the rich and ensuring the poor get enough to eat. In today’s parlance, all this could have been done in 1943 by a series of what are now called ‘executive orders’. But these were not issued!

Sen argued in his other works that food availability in 1943 was “at least 11% higher than in 1941 when there was nothing remotely like a famine”. His theory was war economics was the principal reason behind the ‘man-made’ famine. The Second World War generated jobs in thousands and because they were well-paid, in their new-found affluence, the burgeoning middle-class consumed more than what was needed thereby raising demand by cutting into supply.

On the other hand, while this minuscule minority secured plush jobs, the multitudes who before the war earned only what was sufficient for bare survival, lost employment as nature of economy changed.

Even though there was enough food in the country, disaster struck because the poorest in Bengal could no longer buy food as they had no employment. Even those who retained jobs, could not purchase food as prices had soared and what was within reach previously was now beyond their ambit.

Sen also is known for possibly one of his most significant statements: “No famine has ever taken place in the history of the world in a functioning democracy” because political parties ”have to win elections and face public criticism, and have strong incentive to undertake measures to avert famines and other catastrophes.” He added that “famines are, in fact, so easy to prevent,” and going on to state “that it is amazing that they are allowed to occur at all.”

Despite his argumentative proposition, governments in independent India have continued to show a consistent preference to keep those at the bottom of the economic strata on the edge of malnutrition. P. Sainath’s Everybody Loves a Good Drought remains a lasting contribution deprivation and neglect live side by side.

But for every viewpoint there is also a counter to it and the same data set can be viewed alternately. Several years ago, Madhushree Mukherjee, who has a second-hand experience of the famine similar to mine, wrote the well received, albeit contentiously, Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India During World War II. Unlike Sen, who did not find a villainous character in any individual wielding power, she held just one person responsible for the famine: Winston Churchill.

He was, she argued, responsible for decision that “would tilt the balance between life and death for millions”. She argued her point from another perspective – “one primary cause”, she contended, was the British premier’s keenness “to use the resources of India to wage war against Germany and Japan”. Whatever else may have been her indiscretions, but the one that Mukherjee would find tough to live with was picking a quibble with the economist Sen.

Joseph Lelyveld, when reviewing the book in prestigious The New York Review of Books, refrained from demolishing the book because of her ‘blasphemous’ accusation, but nonetheless began with a simple argument:

‘One primary cause’ is not the same as ‘the primary cause’ but it comes close enough to provide scaffolding for her accusatory title. Probably it’s true that fewer Bengalis would have died had Churchill approved an emergency request from his own officials in India in July 1943 for shipments of 80,000 tons of wheat a month to Bengal for the rest of the year. Whether his failure to do so amounts to a “secret war” is another question.”

The review, sparked an intellectual tempest at the least, as Mukherjee responded to Lelyveld’s comment that she failed in discussing Sen’s claim that that Bengal had enough grain in 1943. Kolkata’s The Telegraph gleefully reported the exchange which was published in NYRB between Mukherjee and the reviewer on the one hand and the fact that Sen to had been drawn into the conflict, this time as an economist who “misquoted the government’s estimate of the rice shortfall as a mere 140,000 tons (instead of the 1.4 million tons stated in the document he cites) — which led him to mistakenly claim that the authorities could not have predicted famine.”

Eventually, the matter remained unsettled and The Telegraph let Ramchandra Guha have the last word in its story: “I think the Bengali intellectual never lost the appetite for debate or quibbling.” Mukherjee has however not given up. A new edition of her book is out to mark 75 years of the Bengal famine and she gets readers to see more of the ‘beastly’ Churchill.

An occasion like this has capacity to induce taking sides. Many have gone along with Mukherjee in vilifying Churchill while others have not – saying that one man cannot be blamed for three million deaths.

That debate apart, there is little denying the deep impact of the tragedy on the Indian psyche, whether they experienced the famine first-hand, second-hand or even have learnt about from remote sources. Mrinal Sen had briefly talked about his film Akaler Sandhane – in the genre of film within a film – and held forth on how even the making of a film on the famine could affect the previously unconcerned crew and cast.

Even Satyajit Ray made Asani Sanket, depicting the life of a young Brahmin couple in a village during the famine. The two films remain testimony to the profound influence of the events of 1942-44. In an iconic shot of Sen’s film, Smita Patil is shown staring into the blinding sky in search for a speck of cloud. But then, in his rush to make his film, Sen possibly stuck with traditional belief that a famine occurs when the rain gods turn disfavourable.

To go back to the point I made initially – every time a ‘conclusion’ is reached, please look for a new perspective. Seventy five years after the famine, it would be fitting for us to think of more ways to understand what happened, how and why. It is also time to write more stories and make more films, not just on this episode, but on all those that have contributed to the making of the contemporary Indian mind.

Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay is a Delhi-based writer and journalist, and the author of Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times and Sikhs: The Untold Agony of 1984. He tweets @NilanjanUdwin.