Somali-American activists recently scored a victory against Amazon and against colourism, which is prejudice based on preference for people with lighter skin tones. Members of the non-profit The Beautywell Project teamed up with the Sierra Club to convince the online retail giant to stop selling skin lightening products that contain mercury.

After more than a year of protests, this coalition of antiracist, health, and environmental activists persuaded Amazon to remove some 15 products containing toxic levels of mercury. This puts a small but noteworthy dent in the global trade in skin lighteners, estimated to reach $31.2 billion by 2024.

Amira Adawe, an activist with The Beautywell Project pickets outside Amazon. Photo: Amira Adawe

What are the roots of this sizeable trade? And how might its most toxic elements be curtailed?

The online sale of skin lighteners is relatively new, but the in-person traffic is very old. My new book explores this layered history from the vantage point of South Africa.

As in other parts of the world colonised by European powers, the politics of skin colour in South Africa have been importantly shaped by the history of white supremacy and institutions of racial slavery, colonialism, and segregation. My book examines that history.

Yet, racism alone cannot explain skin lightening practices. My book also attends to intersecting dynamics of class and gender, changing beauty ideals and the expansion of consumer capitalism.

A deep history of skin whitening and lightening

For centuries and even millennia, elites used paints and powders to create smoother, paler appearances, unblemished by illness and the sun’s darkening and roughening effects.

Cosmetic users in ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome created dramatic appearances by pairing skin whiteners containing lead or chalk with black eye makeup and red lip colourants. In China and Japan too, elite women and some men used white lead preparations and rice powder to achieve complexions resembling white jade or fresh lychee.

In this 1623 portrait by Anthony van Dyck, Elena Grimaldi’s regal whiteness is underscored by a dark-toned servant. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Skin lighteners generate a less painted look than skin whiteners by removing rather than concealing blemished or melanin-rich skin. Melanin is the biochemical compound that makes skin colourful.

Active ingredients in skin lighteners have ranged from acidic compounds like lemon juice and milk to harsher chemicals like sulfur, arsenic, and mercury. In parts of precolonial Southern Africa, some people used mineral and botanical preparations to brighten – rather than whiten or lighten – their skin and hair.

During the era of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, skin colour and associated physical difference were used to distinguish enslaved people from free, and to justify the former’s oppression. Colonisers cast melanin-rich hues as the embodiment of ugliness and inferiority. Within this racist political order, some sought to whiten and lighten their complexions.

By the twentieth century, mass-produced skin lightening creams ranked among the world’s most popular cosmetics. Consumers included white, black, and brown women.

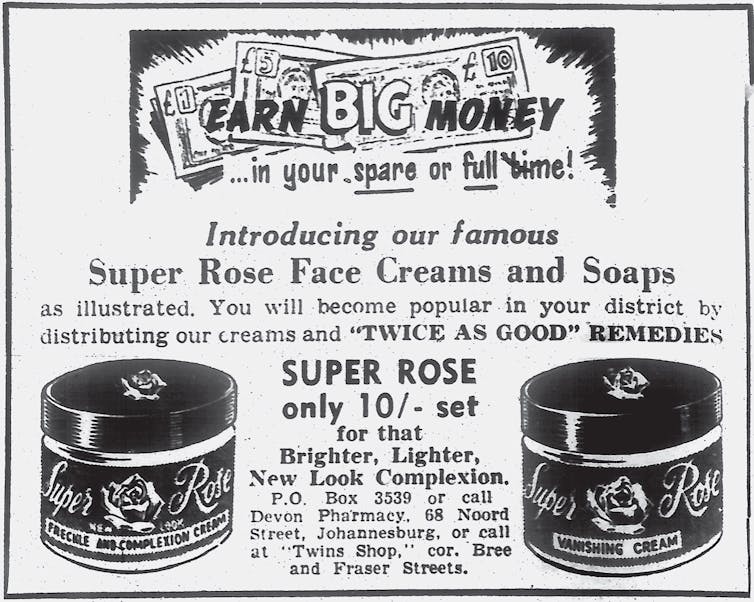

This ad appeared in an issue of the Central and East African edition of Drum magazine. Photo: Duke University Press

In the 1920s and 1930s, many white consumers swapped skin lighteners for tanning lotions as time spent sunbathing and playing outdoors became a sign of a healthy and leisured lifestyle. Seasonal tanning embodied new forms of white privilege.

Skin lighteners became primarily associated with people of colour. For black and brown consumers, living in places like the United States and South Africa where racism and colourism have flourished, even slight differences in skin colour could carry political and social consequences.

The mercury effect

Skin lighteners can be physically harmful. Mercury, one of their most common active ingredients, lightens skin in two ways. It inhibits the formation of melanin by rendering the enzyme tyrosinase inactive; and it exfoliates the tanned, outer layers of the skin through the production of hydrochloric acid.

By the early twentieth century, pharmaceutical and medical textbooks recommended mercury – usually in the form of ammoniated mercury – for treating skin infections and dark spots while often warning of its harmful effects. Cosmetic manufacturers marketed creams containing ammoniated mercury as “freckle removers” or “skin bleaches”.

When the US Congress passed the Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act in 1938, such creams were among the first to be regulated.

Part of Twins’s success lay in their recruitment of hawkers to sell their products in townships. Bona, May 1959. Photo: Duke University Press

After World War II, the negative environmental and health impact of mercury became more apparent. The devastating case of mercury poisoning caused by industrial wastewater in Minamata, Japan, prompted the Food and Drug Administration to take a closer look at mercury’s toxicity, including in cosmetics. Here was a visceral instance of what environmentalist Rachel Carson meant about small, domestic choices making the world uninhabitable.

In 1973, the administration banned all but trace amounts of mercury from cosmetics. Other countries followed suit. South Africa banned mercurial cosmetics in 1975, the European Economic Union in 1976, and Nigeria in 1982. The trade in skin lighteners, nonetheless, continued as other active ingredients – most notably hydroquinone – replaced ammoniated mercury.

Meanwhile in South Africa

Photo: Duke University Press

In the early 1960s, colour photography and printing saw skin lightener ads feature a range of light brown and reddish skintones.

In apartheid South Africa, the trade was especially robust. Skin lighteners ranked among the most commonly used personal products in black urban households. During the 1980s, activists inspired by Black Consciousness and the sentiment “Black is Beautiful” teamed up with concerned medical professionals to make opposition to skin lighteners part of the anti-apartheid movement.

In the early 1990s, activists convinced the government to ban all cosmetic skin lighteners containing known depigmenting agents – and to prohibit cosmetic advertisements from making any claims to “bleach”, “lighten” or “whiten” skin. This prohibition was the first of its kind and the regulations immediately shuttered the in-country manufacture of skin lighteners.

South Africa’s regulations testify to the broader antiracist political movement from which they emerged. Thirty years on, however, South Africa again possesses a robust – if now illicit – trade in skin lighteners. An especially disturbing element is the resurgence of mercurial products.

South African researchers have found that over 40% of skin lighteners sold in Durban and Cape Town contain mercury.

The activists’ recent victory against Amazon suggests one way forward. They took out a full-page ad in a local newspaper denouncing Amazon’s sale of mercurial skin lighteners as “dangerous, racist, and illegal.” A petition with 23,000 signatures was hand-delivered to the company’s Minnesota office.

By combining antiracist, health, and environmentalist arguments, activists held one of the world’s most powerful companies accountable. They also brought the toxic presence of mercurial skin lighteners to public awareness and made them more difficult to purchase.

Lynn M. Thomas’s latest book Beneath the Surface: A Transnational History of Skin Lighteners is available from Wits University Press and from Duke University Press.

Lynn M. Thomas, History Professor, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.