This essay isn’t focused on a historical survey of colourism.

Even if, as Radhika Parameshwaran explains, “There is no established causal relationship or even correlation between skin color and caste. But here’s what I will tell you, there is a strong perception that skin color and caste are linked and as long as that perception lasts, it will matter a great deal. So, I would say there is a widespread and entrenched perception that lighter skin color equals higher caste.”

Instead, the intention is to demonstrate how yoga is employed and perceived to be an instrument to create lighter skin colouration through particular imagined yoga lifestyles. This adds an interesting blemish to the project of branding India through looking at how yoga’s role in soft power strategies is applied via the cosmetic or beauty industry and the unrelenting obsession with fair skin.

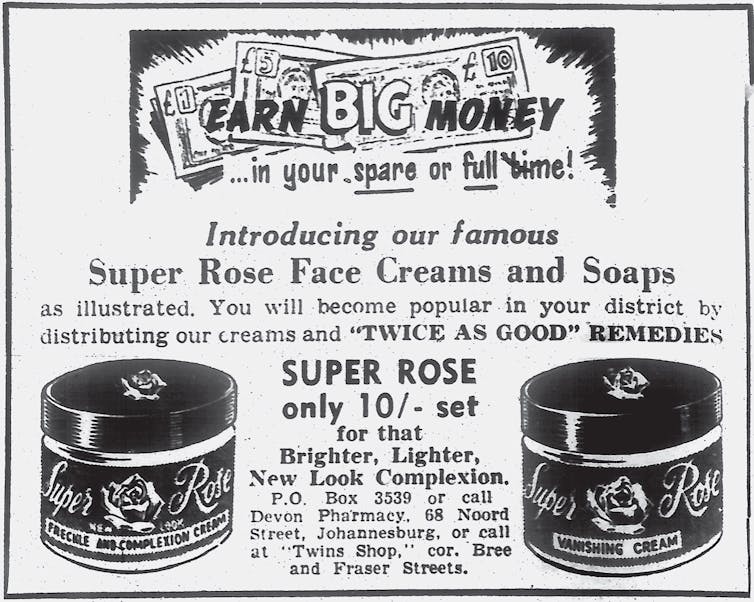

Issues arising from the desire to attain lighter skin colouration is particularly relevant across Asia, Africa, and Latin America where the potential health risks with bleaching skin to attain a prescribed level of beauty are regrettably well known. Many studies show just how pervasive and potentially fatal the practice of using various cremes and lotions are to anyone coerced into aspiring to have “fair” and “lovely” skin. This consumption is linked to leisure behaviours which are tied to cultural perceptions of skin colour.

As Evelyn Nakano Glenn said, “Light skin operates as a form of symbolic capital, one that is especially critical for women because of the connection between skin tone and attractiveness and desirability. Far from being an outmoded practice or legacy of past colonialism, the use of skin lighteners is growing fastest among young, urban, educated women in the global South.”

Yet, this obsession affects both genders. And the industry’s revenue is increasingly driven by men and their demand for skin lightening products continues to grow with the industry projected to hit US$31.2 million by 2024. This is according to a report published by Global Industry Analytics. As Jaray Singhakowinta explains, Thai men are having glutathione injections to whiten their skin and also having laser and chemical treatment on their penises.

Also read: In Bengal, Colourism Hides Behind the Veneer of Bhadralok Culture

As a result of unintended deaths and other health complications, the Ivory Coast banned skin whitening creams in 2015. Just last week Johnson & Johnson announced they are dropping their skin whitening creams altogether. While Unilever’s Fair & Lovely cream is to be renamed.

Prohibition creates…black markets

Practically speaking, if various creams and potions become no longer available through discontinuing products or wholesale banning, how will people continue with their beauty regimes and aspirations? Will this create a situation in which people resort to even more extreme measures that could further impact their health and wellbeing?

It is apparent that not just in India, but across Asia, certain “Yoga lifestyles” and “Face Yoga” methods are offered as “natural” options that do not require cremes, pills, or injections. While it is apparent that this phenomenon has a certain media presence in Asia, it is as yet unclear how deep yoga goes as a perceived path to lighter skin in Africa and Latin America.

South Asian cultures have a complicated relationship with colour. While we ought to be careful of reading into earlier textual sources contemporary ideas and values of racism and colourism, one myth pertinent to understanding some of this complexity and the construction of otherness through colour is the story of King Vena and the origin of the Niṣāda people. One mention includes the Bhāgavata Purāṇa (Book Four, Chapter 14).

Kundan Kumar Raj has said that the Niṣādas were one group of forest-dwelling hunters who existed outside the Brahminical social order and were considered mlecchas (barbarians) in various Puranas. Prior to this the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa (3.2.1.23) defines mleccha as a marker of “barbarian speech”. One example is “helayo helayaḥ” as a variant of the Sanskrit “he’rayo he’rayah,” which means “hail friends!”

This is something that the grammarian, Patañjali, also mentions. These topics have been covered by several eminent scholars. One anecdote is king Brahmadatta Caikitāneya, whose disdain for the accents of others is so much that he cannot even stay in the same territory. This is mentioned in the Jaiminīya Brāhmaṇa (1.337–338). The idea of being an outsider is linked with unrefined or abusive speech (kuyavāc), which in turn is associated with those who have kṛṣṇā-tvac (“black skin”) (Ṛgveda 1.130.08).

Also read: The Indian Hatred for Dark Skin Comes From Caste Bias

In their translation of the Ṛgveda, Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton point out, that “The word ‘color’ [varṇa] in the final pāda of the verse is a frequent way of referring to a cohort, a unified group of people” (Ṛg Veda 1.104.02). And that this hymn refers to the warring of the Ārya with their enemies, namely the Dāsa/Dasya.

Aloka Parasher-Sen elucidates, that “Mlecchas” acts “as a reference group comprised not only foreigners from outside the geographical area of the Indian subcontinent but also included any outsiders who did not conform to the values and ideas and, consequently, to the norms of the society accepted by the elite groups.” And that this was a value shared by Jains and Buddhists against non-conformists.

The use of the term “outsider” (bāhīka) in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa 1.7.3.[8] and its synonym, jahika, in the Mahābhārata 8.30.14 allude to the idea that outsiders had dark skin and spoke differently.

Even though, as mentioned, we ought to be cautious with interpolating ideas of racial, cultural or linguistic prejudice on ancient texts and the groups dwelling within, what is clear is that these issues were important enough for ancient poets to sing about 3000 years ago. More importantly, ideas of skin colour and othering have a much longer history in South Asia that precedes colonialism and Europeans and ideas of “white supremacy”.

Not to say this hasn’t become entangled today, but Pashington Obeng’s book on the history and contemporary issues of Africans in India presents a fascinating account dating back approximately 1500 years. Similarly, Agnieszka Kuczkiewicz-Fraś and Renata Czekalska look at Africans in India and Indians in Africa.

And yet, today, skin colour as a way to mark group identity is as significant as the controversies around it. One only needs to look at the Indian marriage sites to see how important and durable it is. Or, it seems, was. As Shaadi.com has recently capitulated to public protests to remove the skin colour filter from its search engine.

Let’s turn more closely to how yoga and skin colour is entangled. Hydroquinone is the chemical most widely used to lighten skin, yet it is banned in many countries. Not only is yoga promoted as a natural alternative but so are the perceived advantages of Ayurvedic treatments as alternatives for using toxic chemicals like hydroquinone.

For instance, ubṭan is a paste made up of meal, turmeric, oil and perfume. It is rubbed on the body when bathing to clean and soften the skin. While ubṭan is a generic name for ointments applied to the skin, various blends are commercialised that might purport to offer sun-protection and skin-lightening properties that typically include turmeric (Curcuma longa), chick pea (Cicer arietinum), and Indian sandalwood (Santalum album).

Also read: Skin Lightening Is a Dangerous Obsession – and One Worth Billions

Yoga for ‘glowing skin’

The process of “whitening” or “lightening” the skin is often misrecognised through euphemistic expressions, like “reducing dullness” or “increasing radiance” or through “glowing” or creating adjectival phrases, like “fair glowing skin.”

This is seen across the internet. While other examples aim to support assertions that describe the twinkling skin as attainable through six yoga poses for “that radiant yoga glow”:

“We all want beautiful, soft, youthful skin. Sure, potions and lotions help, but real beauty lies beyond man-made products. Gorgeous skin begins internally. And let’s face it, who doesn’t want to feel beautiful from the inside out? A daily yoga practice can drastically influence and rejuvenate your skin. The physical, mental and emotional balance from yoga works similarly to a regular skincare routine, but better. It will naturally enhance your skin, creating a radiant glow. Yoga works in various ways to revamp the quality of your skin. It flushes out and eliminates toxins from the body…”

Yoga is presented as one of five modalities that can help with “face glowing“.

Photo: yogafordaily.com

Where this gets somewhat insidious is that international companies like Loreal are only going part way to solving this issue. Really, their efforts are superficial and only go skin deep by rephrasing their skin products replacing “whitening” with “glow.”

For the time poor busy person who has little opportunity for time pass, one can get all the benefits through “do minaṭ yoga.” If one is looking for something to do during the COVID-19 lockdown then Ira Trivedi offers #YogaIra #Lockdownyogawithiratrivedi in which glowing skin and lustrous hair can be achieved.

Yet other advertising campaigns are more direct with their communication and how it can help with “skin whitening”:

“Graceful, beautiful and glowing skin is in trend. Have you ever wondered how the biggest celebrities of Hollywood & Bollywood maintain their great whitening and twinkling skin all the time? Now it’s time to reveal their top secret, they follow and embrace the Yoga in their lifestyle.”

There are Straightforward Yoga Poses for Skin Whitening which includes the pseudoscientific claim, that “enhancing blood dissemination in your face” is achievable by “turning around the stream of gravity, a headstand reproduces a ‘cosmetic touch up’ by letting your Skin Whitening hang in the inverse heading, which means disposing of wrinkles. The upset position of a headstand likewise flushes crisp supplements and oxygen to the face, making a shining impact on the Skin Whitening.”

It seems, the perception, at least, is that lighter skin is achieved through exercise flushing more blood through the skin and that sweating also seemingly removes, through a sort of tapasya burn off, all the perceived “impurities” of darker pigmentation.

Also read: There’s a Complex History of Skin Lighteners in Africa and Beyond

Abhishek Maheshwari, a yoga instructor offers 10 yoga poses for glowing skin, “Pranayama, breathing exercises, headstand, and fish pose are primarily the best for glowing skin’.

A more comprehensive list of “Yoga Poses for skin whitening” by Sarvyoga, includes: Surya Namaskar (Sun Salutation Pose), Bow Pose (Dhanurasana), Downward Facing Dog Pose (Adho Mukha Svanasana), Plough Pose (Halasana), Shoulder Stand Pose (Sarvangasana), Padmasana (the best Meditation Pose), Corpse Pose (Shavasana).

Photo: vanitynoapologies.com

Ramdev has specific classes on #YogaAsanaForPhysicalBeauty which are problematic for all the essentialised claims made. Here is another example in which Ramdev gives advice over the phone to a woman who wants help with her skin problem.

Photo: YouTube

For all the laudable social justice ideas that an upgraded, yet “true yoga” is about inclusion and access, especially for non-white (BIPOC) people, there is some problem with honouring both its imagined roots and staying true to improving equity and diversity in Yogaland.

Even if spiritual practice and social justice are united through “yoga” to offer events that “reclaim wellness,” ultimately this is just another way to rebrand and create another X+Yoga hybrid that is heretically sealed from criticism through the new religious movement it is inspired by. As Reclamation Ventures is yet another brand capitalising on wellness, spirituality, and social justice activism.

Photo: reclamationventures.co

How are heritage and lineage preserved? What heritage and lineage are preserved?

Alli Simon claims that, “One sutra from the Yoga Sutra of Patanjali states that we are not going to change the whole world, but we can change ourselves and feel free as birds.”

If a classical concept of yoga is perceived to equate to Patañjali’s Yoga Sutras, which many assert it does, and honour this text as some sort of yoga “bible” that contains the definitions for what yoga was, is, and will be, how do we reconcile the obvious issue that this classical version of yoga was prescribed for ascetic Brahmin men?

Also read: Why the Fair & Lovely Rebrand is Too Little, Too Late

And that the aim of Patanjali’s yoga is isolation (kaivalya) and not increasing diversity? Of course, concepts, practices, communities, and meanings change. It is somewhat confusing how yoga heals racial trauma. Does this involve BIPOC people gaining the privilege of whiteness through sweating and gaining “glowing” more “radiant” skin? Is this how racial trauma is healed through whitewashing it?

There is this dark side to yoga that includes its perceived ability to effect change that pathologises dark skin as requiring a remedy or medical intervention. Dark skin is framed as a skin disease that can be alleviated, if not cured, with yoga.

Photo: skindiseaseremedies.com

In Japan, “Face Yoga” has some level of traction that has been exported globally to, at least, keep up with the Kardashians.

Photo: kokofaceyoga.com

However, the original Face Yoga Method™ is also from Japan and similarly claims to help with making one look younger and have more radiant, glowing skin.

Photo: faceyogamethod.com

We ought to consider the insidious changes in language that companies engage with to temper febrile minds regarding the idea of whiteness and the potential hazards of trying to lighten one’s skin colour. Changing the label does little. Yet, even more problematic is the way in which both Yoga and Ayurvedic products and options are promoted as parts of alternative lifestyles that can supposedly make the skin more radiant and glowing.

Again, this does little to actually address the fundamental issues around the insatiable demand by men and women to lighten the colour of various body parts. And somehow this has evolved to cross over with wellness and spirituality with social justice actions to create an affirmative “self care” environment.

However, like the dualistic philosophy that underpins yoga’s metaphysics, sāṃkhya, “Yoga” seems to be engaged in a metalevel double entendre (sleṣa) whereby it is able to generate self acceptance and cure pathologies that come with being othered as well as having kṛṣṇātvac (black skin) and being an outsider (bāhīka).

Patrick McCartney, PhD, is a Research Affiliate at the Anthropological Institute at Nanzan University, Nagoya, Japan. He is trained in archaeology, anthropology, sociology, and historical linguistics. His research agenda focuses on charting the biographies of Yoga, Sanskrit, and Buddhism through a frame that includes the politics of imagination, the sociology of spirituality, the anthropology of religion, and the economics of desire. His social media handle is Patrick McCartney.