Most anganwadi workers make less than minimum wage, yet their demands for better wages and facilities are ignored.

Children standing outside their anganwadi centre that runs from a small rented room in the basti. Credit: Shruti Jain

Jaipur: “It’s 7:45 already,” Rekha Devi siad as she knocked on the rickety old door of a shanty house in Fauji basti. “Is Nandini ready?”

“Madam, Nandini’s stomach is upset today. She will bother you every 15 minutes to take her out for toilet. How will you manage? I’ll send her tomorrow,” Nandini’s mother replied from behind the door.

“She wouldn’t have missed her classes today if the anganwadi had a toilet,” Rekha thought to herself, as she led her other students to the centre. Once there, she took attendance. “Eighteen out of twenty. That means the class will be conducted outside. Thank god the weather is nice,” she thought.

The kids scattered outside the dilapidated room, into the fresh air. There is an unusual commotion, which Rekha struggled to control. “No food for you all if you don’t concentrate on your lesson today,” she screamed. The cheerful faces puckered into frowns and pin-drop silence was restored.

§

Jyoti Sharma, an accredited social health activist (ASHA) at Vidhyadhar Nagar anganwadi centre (AWC) in Jaipur, left her job at a private school ten years ago to join the anganwadi, which she assumed to be a government job. She is a single mother, and her salary is insufficient to run her household. She stitches clothes at night to make a little extra. But with expenses increasing every day, she constantly wonders about how much more she would’ve earned at her old job at the private school.

Having heard the assurances before every election – of ‘government employee’ status, her children’s education sponsored after class 8, a promotion to lady supervisor and entitlement to the minimum wages – Jyoti doesn’t have much hope. But recently, she and other anganwadi workers and ASHAs have begun to protest for those promises to be met.

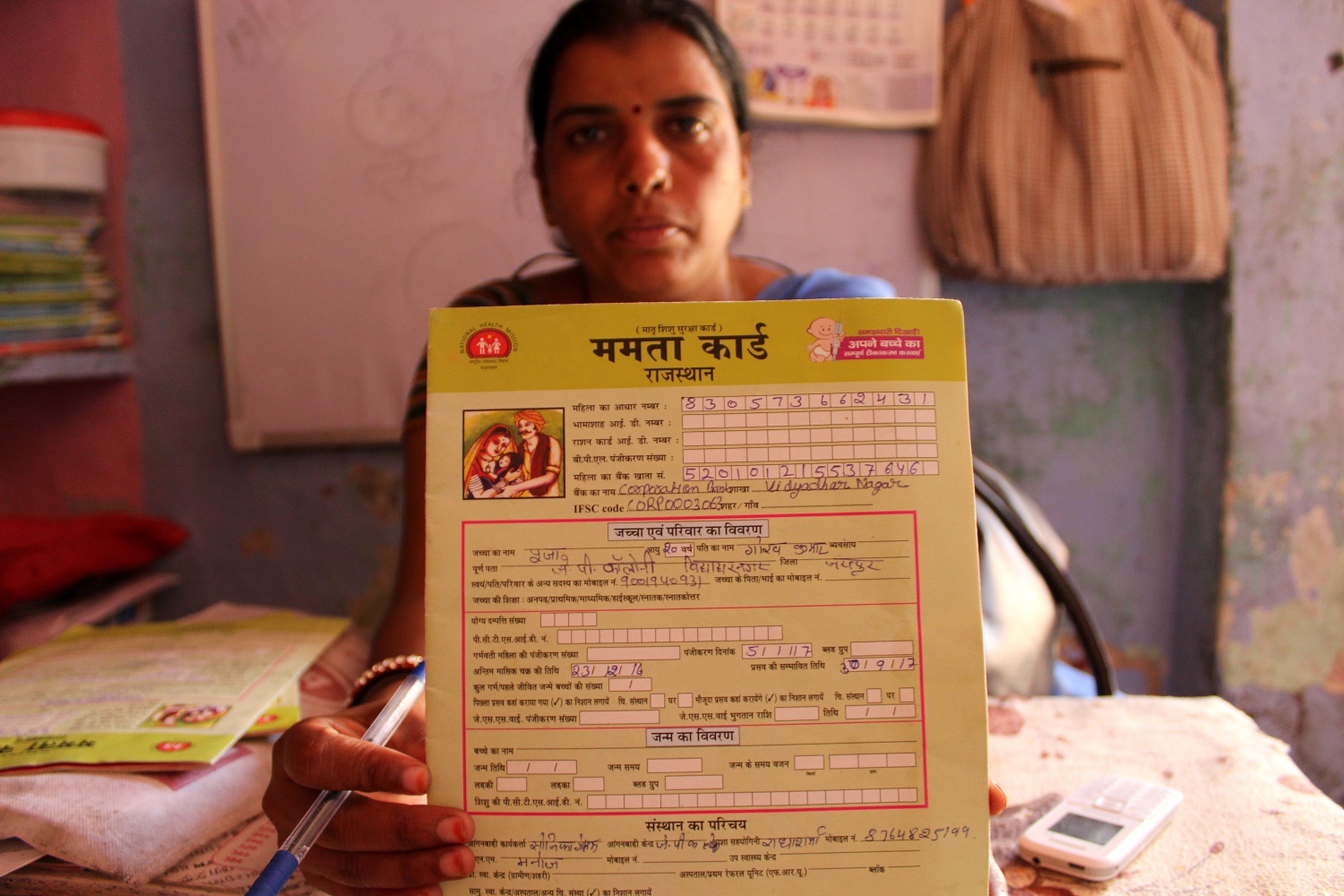

The Mamta card requires details of Aadhaar card, Bhamashah card and bank details. Credit: Shruti Jain

Struggling to pay the rent

The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme has existed since 1975, offering rural children a package of six services – supplementary nutrition, preschool non-formal education, immunisation, nutrition and health education, referral services and health check-ups through AWCs.

AWCs are located in rural villages and wards in urban slum areas, covering a population of 800. The communities are expected to organise a space, though for about a third of anganwadis, the government pays rent: recently upgraded to Rs 750 for rural and tribal projects, and Rs 3,000 for urban projects, if the room is at least 500 square feet in size.

Finding the space, however, and negotiating the rent falls on anganwadi workers like Jyoti.

“Which world are they living in,” asked Indra Devi (35), an anganwadi helper at the J.P. colony AWC. “Monthly rent for just a 70-sq. ft. room in a kachi basti is Rs 1000-1500, forget electricity, toilet and water connection. We are forced to pay the rest from our already low salaries.”

Going outdoors

According to the Ministry of Women & Child Development, in 2014, many AWCs didn’t have toilet facilities, forcing the children to defecate in the open. Even if someone houses to do a toilet, owners typically allow the anganwadi workers to use the toilet but restrict the children from using it.

“In the government data, we have toilet facility at the centre but our kids go out in open,” said Rekha Devi. “Actually, the owners have their own issues. With limited water supply, they find it difficult to maintain the hygiene if so many people use it.”

The budget crunch afflicts other parts of the ICDS as well. Supplementary nutrition is provided to children upto six years old (with special provision for malnourished children), pregnant women and nursing mothers, in the form of morning snacks, hot cooked meals and take home ration (THR) packets.

In most of Jaipur’s AWCs, hot cooked meals are supplied by the Akshay Patra Foundation. Self-help groups (SHGs) are entrusted with producing the THR packets, usually a cereal called panjiri. But the SHGs complain about low and irregular payments for this essential service. “The actual cost per packet comes around Rs 50, but we are paid only Rs 33.75 by the government,” said Sangeeta Sharma, part of the Riddhi Siddhi SHG in Bapu kachi basti. “It’s a complete loss for us.”

Unaccounted work is unpaid work

The Department of Health and Family Welfare is meant to pay incentives to ASHAs for facilitating health-related services in the community. In theory, they can earn upto Rs 2,000 per month but claims for payment are rejected if there is a discrepancy between the beneficiary’s Aadhaar card and their address on the hospital discharge sheet. Claims are also denied if a pregnant woman delivers at a private hospital instead of a government hospital.

Many slum residents are migrants; if they have an Aadhaar card, the address often doesn’t fall in that particular ward. In both cases, ASHAs are denied payment. Without an Aadhaar card, the mothers are also denied the state government’s Mukhyamantri Rajshri Yojana grant, worth Rs 50,000 on the birth of a girl child.

“We take care of every pregnant woman in the locality but the government discriminates against them,” said Urmila Agarwal, an ASHA in Kishan Bagh anganwadi.

Besides their daily duty at the centres, the anganwadi workers and ASHAs are burdened with tasks that include surveying for government schemes, for diseases like swine flu and malaria, election duty, pulse polio camps, municipal corporation camps and mass-marriage ceremonies.

For the Modi government’s Mission Indradhanush scheme, ASHAs are paid mere Rs 100 to cover a population of 1500 persons. For a five-day duty at the pulse polio camp, they get only Rs 300.

“For duty in the elections, they pay us nothing,” said Jyoti. “Who wishes to work for this amount? We spent more than Rs 100 traveling across the anganwadi region for the survey.”

Below minimum wage

In Rajasthan, anganwadi workers earn a monthly honorarium of Rs 4,730, helpers earn Rs 2,565 and ASHAs Rs 1,850.

“We don’t even get minimum wages, because the AWCs open for four hours and the government counts our working hours as only six hours – two hours less than the eligibility criteria for minimum wages,” said Khushboo Sharma, an anganwadi worker in Fauji basti. “They won’t consider the time consumed in additional activities they use us for.”

Speaking to The Wire, Rajasthan’s ICDS director Suchi Sharma said, “We are sensitive to their demands but they need to be logical. We can’t just double their salaries. We don’t have the budget to pay what they are demanding. Also, they aren’t liable for minimum wages since they work only for four hours a day.”

Last month, Rajasthan’s ASHA and anganwadi workers went on a 21-day protest demanding a salary hike. It was called off abruptly after their leader, Chotelal Bunkar, signed an agreement with the Department of Women and Child Development abandoning the demands of thousands of women.

Shruti Jain is a freelance journalist.