The recovery of the Kolar Leaf-nosed bat from the IUCN’s endangered Red List is thanks to the scientists like Bhargavi Srinivasulu, who convinced the IUCN to raise the alarm.

Bhargavi Srinivasulu is a Hyderabad based chiropterologist. Credit: The Life of Science

In 2016, Hipposideros hypophyllus slid to the bottom of a list that no species wants to be on – the ‘Critically Endangered’ section of IUCN’s Red List. The assessors stated that only 150 to 200 of these creatures remain, all of them confined to a single cave near the village of Hanumanahalli in Kolar, Karnataka.

Today, the bat commonly known as the Kolar Leaf-nosed bat is doing a lot better thanks to the efforts of the zoologists who made the assessment and convinced IUCN to raise the alarm. Bhargavi Srinivasulu is one of them (the other two are Rohit Chakravarty and Chelmala Srinivasulu).

Srinivasulu works in the zoology department of Hyderabad’s soon-to-be century old Osmania University. Like the rest of the buildings in its sprawling campus, this one too is monumental with high cobwebbed ceilings and wide corridors dimly lit by the sun through decorative windows. One of the corridors led me to Bhargavi.

“Since 2003, I have been going to different places to find what kinds of bats are there… are there any new species in the ecosystem? Once we have an idea, we can talk to government officials and come up with action plans for conservation efforts if needed,” said Bhargavi.

The re-discovery of the Kolar Leaf-Nosed Bat is among her most memorable ventures. This particular bat was first documented in 1974, though it was only later correctly identified. It was said to exist in subterranean (underground) caves, but nothing much else about its population nor about its appearance was studied or known.

Striking gold in Kolar

Srinivasulu had a hunch that these bats might be endangered and decided to go looking for them. In 2013, with the help of a grant from the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, she was able to pursue this search. She started her survey on the bats’ supposed home ground, the former gold mining district of Kolar in Karnataka.

So how does one go looking for a specific kind of bat? Turns out, all you need to do is ask, and Srinivasulu was by then experienced enough to ask the right people. “I especially approached old people because when they were young they would have gone around with their cattle and they will know many things about the place, unlike the younger generation who go to work to towns and urban areas.”

Most of her interviews involved asking the people: first, if they have seen bats around the area; second, if there are any cave sites around the area, and third, would they lead her there. Through this line of questioning, she and her teammates were led to two subterranean caves in the area – one in Hanumanahalli and the other in Therhalli.

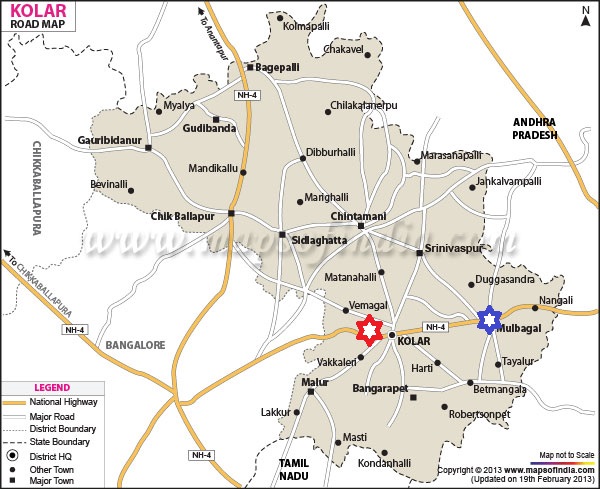

Map of Kolar. Therhalli is the red star while Hanumanahalli is the blue star. Credit: The Life of Science

But the real stroke of luck came when Srinivasulu serendipitously met the grandfather of their young local guide. While unwinding at the old man’s shop after a long unsuccessful day searching for the bat in Therhalli, she introduced herself, her team and their mission. He responded with the recollection of meeting scientists just like them many decades ago – around 1974 – when he was a youngster. He directed them to Hanumanahalli, where he knew of a cave with bats; at that point, Srinivasulu reminded me, they had no clarity about what species he was talking about – “he could not know what kinds of bats were there, so we just went knowing that we might find bats there”.

In Hanumanahalli, Srinivasulu saw a huge monolith (made of a single rock) hill ahead of her. She immediately wondered if the hill may have crevices or caves – potential bat homes. At the site, he also noticed suspicious activities afoot. The monolith was dotted with lorries and she soon realised she was witnessing illegal granite extraction. The workers were chipping away at the granite that the hill was made of and loading it onto trucks.

Undeterred, the team of zoologists proceeded up the hill to search for bat roosts. They found a roosting site in a gap between sheets of rock but it was burnt. “It becomes easy to extract a slab of granite if you burn the rock,” she explained. “The roosting site had lots of faecal pellets (poop) but they were covered with soot. It looked like the roost had been abandoned, so we kept climbing.”

That’s when they came across another old man who claimed to have also helped the 1974 team. He said he had gone inside a cave and collected bats and pellets for them. But where was the cave? He pointed down the hill to a tree. They followed his directions and there, nestled between two sheets of granite was what they had been waiting for – a seemingly active roosting site.

“We could smell heavy bat guano (poop). We waited until night, put up a couple of mist nets (a nylon net suspended between two poles used to trap bats), and captured some of these bats.” Srinivasulu and her team became the first ones to ever photograph the Kolar Leaf-Nosed Bat.

Fixing a broken hill

They went back again the next year and this time all of them got a closer look. “We all went in… we had to lie on our stomachs to crawl in and take pictures inside,” she reminisced. This time, in the same cave, they found another endangered species of bat that was only thought to exist in Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh. “This was super exciting!” Srinivasulu said, her eyes gleaming. “That particular cave is now a (known) home of two endangered bat species!”

The excitement was dampened when Srinivasulu realised the severity of the threat faced by the bats due to the mining. The scientists’ guesstimated that the Kolar Leaf-Nosed Bats occupy less than 10 km square and only 150-200 individuals remain.

It was time to take some action. “We approached the collector and sensitised villagers about what was happening. The hill also had religious significance for them as Goddess Sita is believed to have nursed her son on the rock… [We suggested to them] that could that be why they are not getting rains. We added scientific facts, too, saying that the mining would destroy the ecosystem, you won’t get proper rains, groundwater… we did this repeatedly over two years.”

According to Srinivasulu, due to her team’s efforts, the villagers have now become “custodians of the land”. Moreover, the collector alerted the Mines and Geology Department in Kolar prompting them to issue a ban on mining activity in that area. There have also been discussions about declaring it as a protected area so that in the future, collection for scientific purposes also does not happen. “We have collected around four bats to study them and confirm the species type. Even if people like us keep going there, we could lose the species,” cautioned Srinivasulu.

Today, the habitat has improved so much that there is a water body near the hill that is completely filled. Srinivasulu is heartened to see greenery around and improved groundwater levels. “Before, people were cutting trees to make a path for trucks,” she said, “Now all of this has stopped and everything is back to normal!”

Batty about bats

India is rich in bat diversity – over 100 species exist. Most of these are insectivorous (eat only insects and sometimes small frogs and birds or fish) and the rest are frugivores (eat only fruits, tender leaves and nectar from flowers). Considering this abundance, Bhargavi laments the shortage of chiropterologists (bat scientists) in the country. “Lots of people work on tigers and snakes – many romantic things about these animals that can catch your eye easily and make you famous fast. But not many people work on bats which are extremely helpful to humans.”

Srinivasulu tells us why bats matter

|

A prod towards a PhD

Growing up in Hyderabad, Srinivasulu did not dream of becoming a chiropterologist. She loved biology, but caught up in the hype of her time, she only thought of that as a route into medicine. When she didn’t make the cut, she went ahead and pursued a B.Sc in the subject she enjoyed the most. In college, she met Chelmala Srinivasulu who she eventually married after her M.Sc.

“I did not have any plans of studying further because I come from a very conservative background and M.Sc was it for me – what comes after that I didn’t think,” said Srinivasulu. But her husband had some ideas for her. “He said ‘I’m going to do my PhD – you also have to do it’. He started his PhD in ‘96 and slowly I also began to get interested. I registered for mine under the same guide. When I was reading, he was doing fieldwork. He used to catch bats and come back and describe them to me. That’s when my interest in bats started.” Since her husband was working on fruit bats, she decided to pursue insectivorous ones. The two started their research on the only flying mammal at a time there were barely any taxonomy studies coming from India.

Any apprehensions from her family dissolved, said Srinivasulu, since all her adventures came after marriage. “Initially, I was accompanied by my husband, as we went to the same place. We have a son and we used to take him along since he was young. But since 2012, I have been leading my own team, planning my own work. I’ve had no issues at all.”

Roost in peace

Crawling into dark, stinky bat roosts – isn’t it risky? Not at all, responded Srinivasulu. “It’s wonderful to see bats there. It gives me such a happy feeling that they are there.” In fact, she considers misconceptions like mine a great threat to bats. “Elders say bats will poke your eye, get into your hair, ears. Wherever we went, people said ‘oh you work on bats! They will bite you.’ Because of these misconceptions, many people destroy bat roosts. If a bat flies inside through a window (mistaking the house for a safe place), people consider it a bad omen, leave home or do pooja,” she laughed. “It’s just an animal!” What about diseases like Ebola which originated in bats, I countered. “There’s no real health hazard,” she clarified. “Even if it bites you, it’s very rare for viruses to cross over the species barrier.”

Srinivasulu during a field study. Credit: The Life of Science

Climate change isn’t helping either. Cave systems are generally cooler than the outside environment so you would expect the bats to be immune to rising temperatures, but this is not so. “Let’s say these bats are used to eating a particular kind of insect in October. But because of climate change, winters are not as cold as they used to be and this insect may no longer be available in October. It may get replaced by an insect that bats don’t feed on. It may take a generation to get used to this new insect or the bat species may not survive the loss, leading to a population crash.”

“Now bats have to fly 15-20 km to find fruits. That is putting too much strain on them because of which they are not giving birth, or not able to feed the pups… this population is drastically decreasing.”

The only way out is making people more aware and then work with government officials. Srinivasulu believes conserving ecological systems needs to follow scientific findings. For example, cutting down forests should accompany reforestation efforts that match the existing ecology. If there are fruit bats in the ecology then we need to be careful to plant ‘useful trees’ with fruits – not simply those that will make the environment ‘green’. “This way, the bat population is also taken care of, you get greenery and you can have development, too.”

Journey in science as a woman

There’s no special challenge being a woman on the field, said Srinivasulu. “You just have to believe in yourself. There’s nothing to be scared of. In the field, there will be people to help you out. When I went to the Andamans with my team, I took the locals’ help as they know the area very well. That was the first time I scaled vertical walls to get into a cave! Let the locals guide you. Just be nice, polite… be normal.”

Research turned out to be very convenient for Srinivasulu during her early years as a mother. “It gave me the flexibility of not reporting to work every single day and working from home. I used to work on papers all day and take care of my son, too. We didn’t need much help as we both were in research, we could complement each other.”

Today, the Srinivasulus are a family of bat lovers. Their son is 18 years old, currently doing his graduation in zoology, and already publishing papers. “He contributes equally, he’s gone inside caves just like us and is passionate about science.”

This piece was originally published by The Life of Science. The Wire is happy to support this project by Aashima Dogra and Nandita Jayaraj, who are travelling across India to meet some fantastic women scientists.