Investigations into accusations of public officials’ corruption need to be sanctioned by the government before they begin, a new state ordinance says.

Rajasthan chief minister Vasundhara Raje. Credit: vasundhararaje.in

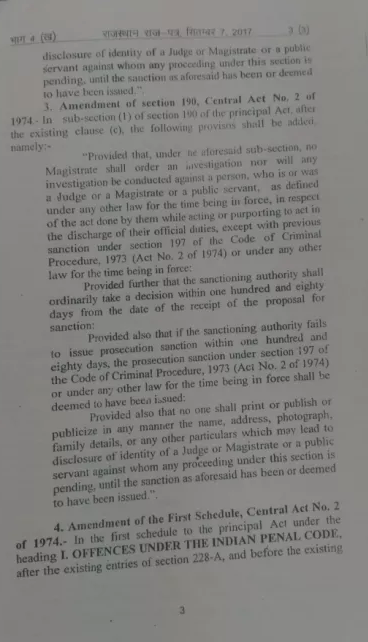

Jaipur: A new ordinance from the Vasundhara Raje-led BJP government in Rajasthan, tabled in the state assembly on Monday (October 23), restricts any investigation against “a judge or a magistrate or a public servant” with respect to “the act done by them while acting or purporting to act in discharge of their official duties” without prior sanction from the government, which may take up to six months. The ordinance has also given public servants under investigation the same privacy rights as survivors of sexual violence – their names and other identity-related details cannot be made public. The protection offered to victims of rape under IPC Section 228a is now offered to public servants, under Section 228b.

As reported by The Wire earlier, the ordinance stops the media from reporting on accusations against a public servant until the government allows it.

Connotations of replacing ‘cognisance’ with ‘investigation’

According to Section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, “if an offense is committed by a public servant while acting or purporting to act during discharge of his official duty, sanction may be necessary before the court takes the cognizance of the offence”.

According to Section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, “if an offense is committed by a public servant while acting or purporting to act during discharge of his official duty, sanction may be necessary before the court takes the cognizance of the offence”.

Police register FIRs only for cognisable offences, where an arrest can be made without a warrant (rape, murder or corruption, for instance). As soon as an FIR is registered, the police acquires the power to investigate. After the investigation is complete, the police prepare a report called a chargesheet, challan or final report recommending punishment to certain persons and submit it to the magistrate. After looking at the chargesheet, when the magistrate decides whether there is substantial material to start a trial against the accused, she is said to have taken cognisance of the offence. However, instead of requiring government sanction only before the step of cognisance, the new ordinance disallows even investigation without prior approval.

“Prior to the ordinance, there was no compulsion to have government sanction first and only then start proceedings. It could be attained any time before the completion of the trial,” a criminal lawyer who didn’t wish to be named told The Wire. As per the new ordinance, the investigation itself requires a sanction, raising doubts on whether FIRs will be registered at all in corruption cases against public servants in the state.

In cases when the police refuse to register an FIR, a person can make a complaint to the superintendent of police or ask the magistrate to direct the police to investigate, according to the CrPC. However, the ordinance adds the following to Sections 156 (3) and 190 (1) of the CrPC, weakening that power: “Provided that, under the aforesaid sub-section, no Magistrate shall order an investigation nor will any investigations be conducted against a person, who is or was a Judge or a Magistrate or a public servant, as defined under any law for the time being in force, in respect of the act done by them while acting or purporting to act in discharge of their official duties, except with previous sanction under section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973.”

“The effort is to defang the police and investigating authorities by removing powers vested in them by law to initiate even a preliminary inquiry,” Radhakant Saxena, former IG, Prisons (Rajasthan) told The Wire.

Accused public servants are victims

After Section 228a of the IPC, which deals with protecting the identity of victims of sexual offences, the ordinance inserts Section 228b, called ‘Disclosure of identity of certain public servants’. The ordinance reads:

After Section 228a of the IPC, which deals with protecting the identity of victims of sexual offences, the ordinance inserts Section 228b, called ‘Disclosure of identity of certain public servants’. The ordinance reads:

“Provided also that no one shall print or publish or publicize in any manner the name, address, photographs, family details, or any other particulars which may lead to disclosure of identity of a Judge or Magistrate or a public servant against whom any proceedings under this section is pending, until the sanction as aforesaid has been or deemed to have been issued.”

“It is illogical and funny to club corrupt public servants with rape victims under Section 228 of the IPC dealing,” said Saxena.

The ordinance also prevents the media from disclosing the identity of accused public servants until the sanctioning authority permits it.

“Whoever contravenes the provisions of fourth proviso of sub-section (3) of section 156, and fourth proviso of sub-section (1) of section 190, of the code of the Criminal Procedure, 1973 shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a term which may extend to two years and shall also be liable to fine.”

Interestingly, though the ordinance was brought by the BJP government one month ago, it has not been uploaded to any government department website. Not even a press note was publicly available on the ordinance.

“This clearly shows that the intent was to suppress the information from the public, forget holding pre-legislative consultation, an imperative issued by the UPA government in January 2014,” said NGO People’s Union for Civil Liberties’ (PUCL) in a statement yesterday.

BJP government defends the move

The Rajasthan government in its press statement said, “Continuing on its policy of zero tolerance towards corruption, the Rajasthan government has not spoken anywhere in the ordinance to provide protection to corrupt public servants.”

Defending the rule, the government yesterday shared data from 2013 until June 2017, claiming that 73% of cases filed under Section 156 (3) of the CrPC were found to be false. “Rajasthan is not the first state to make such amendments in CrPC. Maharashtra legislative assembly has passed an amendment of this effect in December 2015. The only intention behind the ordinance is to protect the image of honest and devotional officers from the misuse of Section 156 (3),” the statement says.

Speaking to The Wire, Kavita Srivastava, PUCL’s Rajasthan president said, “The ordinance has exposed the motivated nature of the government to somehow protect corrupt public servants and to win their support for the ruling party. The government wants to silence the media and to prevent the judiciary from exercising its judicial function of setting the criminal law in motion. We demand that the government immediately repeal this ordinance.”

Shruti Jain is a freelance journalist.

Comments are closed.