To counter the civil rights movement, Alabama had passed a law protecting the reputation of public officials, and the justification given for it was eerily similar to that given by the Rajasthan government.

In 1964, the Supreme Court of the United States was faced with a question that in some shape or form will soon reach the door step of the Rajasthan high court, if it hasn’t already.

Alabama had passed a law that said any person who published any statement that injured the reputation of a person in public office or imputed misconduct to him/her would be per se [i.e. automatically] liable for libel. This meant that any aggrieved public official who simply proved that a publication identified him or her and harmed his or her reputation would walk away with a fortune while single-handedly reducing the publisher to insolvency. The only defence available for the publisher was proving that the facts published were true in their “entirety”, a standard almost impossible, since the slightest unintended error would ruin any defence.

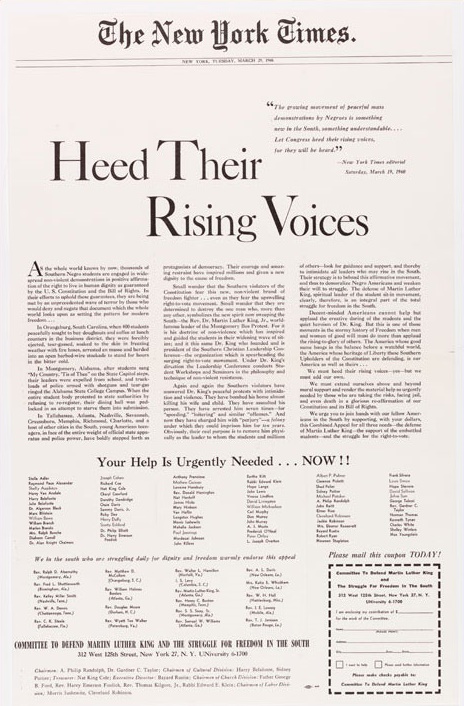

Taking advantage of this law, a city commissioner in Alabama, L.B. Sullivan, sued the New York Times for an advertisement that held ‘unnamed city officials’ responsible for the illegal arrest of the famous Reverand Martin Luther King Junior, amongst other atrocities. The plaintiff, Sullivan, convinced a trial court jury that the New York Times‘ advertisement sufficiently identified his person and harmed his reputation. Since there were some factual inconsistencies, albeit minor, the defence fell. The trial court granted Sullivan $500,000 in compensation and the Alabama Supreme Court upheld this decision.

The New York Times then mounted a constitutional challenge before the US Supreme Court, to decide whether “the Alabama law that allowed public officials to sue critics of their official conduct, abridged the freedom of speech and of the press”.

Alabama’s obvious justification for such a law was that it protected the reputation of public officials and prevented any unwarranted harassment while discharging public duties.

This justification is eerily similar to that given by the Rajasthan government for the promulgation of the Rajasthan Criminal Laws (Amendment) Ordinance, 2017 on September 7 this year.

The ordinance has a two-fold effect.

Firstly, it makes it tougher to sanction the prosecution of government officials, which has created a hue and cry across the country. However, legally speaking, this goal of the ordinance may survive given that Section 197 of the Code of Criminal Procedure makes it tough to prosecute public servants’ without sanction and the court will have to weave itself through a maze of judgments and then split hairs over the difference in the legal definition of “investigation” and “prosecution”.

It is the second effect of this ordinance that is staring at a constitutional death knell. Briefly stated, the ordinance prevents ‘the publication in any manner of any particulars that may lead to the disclosure of any public official’s identity, pending an official sanction for his or her investigation’. It then makes a contravention of this law a criminally punishable offence. Under such a draconian law, one can foresee even criticism of a public official falling under its purview.

Also read: Rajasthan Government Moves to Gag Media From Reporting on Official Wrongdoing

Reverting to the Alabama case, the US Supreme Court in New York Times vs Sullivan unanimously held that the Alabama law was unconstitutional even if it was made to punish “falsely made libelous statements”. Justice Brennan who delivered the opinion of the court, went on to hold that publishers could be held liable only for defamatory actions made with proof of actual malice or the knowledge that such statements were made with reckless disregard. It’s worth quoting Justice Brennan here:

A rule compelling the critic of official conduct to guarantee the truth of all his factual assertions – and to do so on pain of libelous judgement virtually unlimited in amount – leads to…’self-censorship’……Under such a rule, would be critics of official conduct may be deterred from voicing their criticism, even though it is believed to be true and even though it is in fact true, because of doubt whether it can be proved in court of fear of the expense of having to do so… The rule thus dampens the vigor and limits the variety of public debate.

The outcome was that the US Supreme Court unanimously struck down the Alabama law on the ground that free speech ought to be so highly protected that even false speech in itself was not ground enough for civil or criminal sanction.

The New York Times page

Sadly, the Rajasthan ordinance can’t be struck down on grounds akin to New York Times vs Sullivan since the Indian Supreme Court has taken the view that freedom of expression in India is accorded lesser protection than in the US. In India, false statements that injure reputation are punishable irrespective of malicious intent or degree of negligence. In the Subramanian Swamy case, 2016, this view was encapsulated in the following words:

The protection given to criticism of public officials even if not true, as in the case of New York Times v. Sullivan [29 LED 2d 822 (1971)], is not protected by Article 19(1)(a) as this Court has noted that there is a difference between Article 19(1)(a) and the First Amendment to the US Constitution”, and acceded to by the Supreme Court.

Given this position, the freedom of the Indian press is already easy prey to public officials and public figures that wish to stonewall any accountability in public life.

However, the Rajasthan law goes much farther than just forcing the press to “self-censor”. The ordinance which holds that: “No one can publish or print or publicise in any manner the name, address, photograph, family details or any other particulars which may lead to disclosure of identity of a judge or magistrate or a public servant against whom any proceeding is pending,” until a sanction is received, creates a legal effect known as “prior restraint”.

In simple terms, a prior restraint is a law or governmental action that creates a temporary or permanent ban on the very expression of any form of speech. In more sophisticated terms the jurist William Blackstone explained prior restraint as:

The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state; but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published.

Also read: In Rajasthan, Rape Survivors and Officers Under Investigation Now Have the Same Privacy Rights

The Rajasthan ordinance is a textbook example of ‘prior restraint’, since no allegations, even if entirely truthful, can be published “in any manner” without prior sanction. Thankfully, the Supreme Court of India has held prior restraint to be unconstitutional, albeit with qualifications concerning broadcasting and licensing rights. As early as in 1950, the Supreme Court in the Brij Bushan case held that:

There can be little doubt that the imposition of pre-censorship on a journal is a restriction on the liberty of the press which is an essential part of the right to freedom of speech and expression declared by Art.19(1) (a).

This view has gained strength through the years and has been adopted by the court even in a recent PIL filed earlier this year. Rarely has a scam in India led to punishment of the guilty that was not sourced or fuelled by the press. The fourth estate has always stood tall in promoting accountability in public life, and one shudders to think what could happen if this foundational brick in our democratic wall is hammered out. While India hasn’t held itself to the Alabama case standard, one only hopes that the courts prevent our fall to Raje’s standard and safeguards an already eroded constitutional right.

Abishek Jebaraj is a Delhi-based lawyer.