Qurratulain Hyder’s final novel revolves around how the coexistence of a temple and a mosque on the same piece of property has the potential to flare up into a full-scale conflagration.

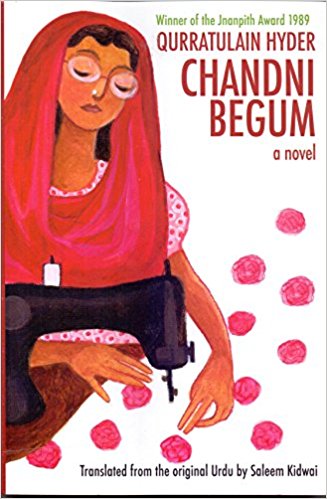

Hyder’s craft as a natural storyteller made her an unparalleled writer in the world of Urdu literature, and in Chandni Begum, she summons all the gifts at her disposal. Representative image credit: Wikimedia Commons

When Qurratulain Hyder wrote Chandni Begum, her last novel, in 1989, L.K. Advani’s rath yatra was still a year away, the Ram Janmabhoomi movement was just about taking off and the first BJP government under the prime ministership of Atal Bihari Vajpayee was still years away.

Of course the mandir-masjid issue at Ayodhya had been simmering for years. Hyder understood how land could be a contentious issue and how the unremarkable coexistence of a temple and a mosque on the same piece of property had the potential to flare up into a full-scale conflagration.

Chandni Begum traverses a vast terrain over generations and its emotional centre is not just the intertwined lives of three families but also the remains of a house known as Red Rose.

Red Rose and its accompanying orchards is at the emotional heart of the novel.

Home to Shaikh Azhar Ali, a successful barrister, his social reformer wife, Badrunnisa Azhar Ali aka Bitto Baji, and their son, Qambar Ali, “a young man of modern times who made fiery speeches against private property”, it is also home to Munshi Bhawani Shankar Sokhta, Shaikh’s loyal secretary and a vast retinue of servants. It is for the munshi that a small temple exists on the estate.

As a child, Qambar was engaged to marry Safia Sultan, the youngest daughter of a minor raja of a principality called Teen Katori. But as Qambar grows older and more revolutionary, the thought of marrying into such a family with its rigid notions of class becomes anathema and he instructs his mother to find someone who is highly educated, poor and beautiful (of course).

Chandni Begum, the daughter of Baji’s childhood friend, fits the bill. She has a master’s degree. And despite her lineage – her maternal grandfather owned 52 villages and her paternal grandfather had the title of Khan Bahadur – has fallen on hard times after her father deserts her mother. When Baji suggests a marital alliance, everything seems sealed.

But Shaikh and Bitto Baji die unexpectedly, soon after each other, and the proposed marriage is forgotten. Qambar is now a man of means, free to spend his inheritance on an unsuccessful election run and on his magazine, Red Rose, published in Urdu (Gul-e-Surkh) and Hindi (Lal Gulab) as well.

Into this world arrive from the chawls of Mumbai, the colourful though somewhat dodgy members of the Sanobar Film Company headed by Master I.B. Mogra, his wife Chameli Begum (‘film star and poetess’), son Parizada Gulab (‘comedian’) and daughter Bela Rani Shokh (‘radio singer and poetess’). The young and idealistic Qambar is easy pickings and ends up with a runaway nikaah with Shokh.

Qurratulain Hyder, translated by Saleem Kidwai

Chandni Begum

Women Unlimited, 2017

Shokh manipulates getting Red Rose as her mehr, but the marriage is an unhappy one. With nothing to do, she begins rearranging the affairs of Red Rose – adding a modern kitchen, buying nursery furniture for non-existent children – and haranguing Qambar for more money while she whiles away her time shopping.

Then unexpectedly, Chandni Begum arrives. She has lost her teaching job, her mother has died and she has nowhere to turn to. The shrewd Shokh realises that Qambar could be a soft touch and so packs Chandni off to Teen Katori, home of Safia Sultan, Qambar’s former fiancée.

Chandni is not treated well at Teen Katori, relegated to the position of a servant. The elder son (suspected of being deranged) wants to marry her, the younger one wants to make her his mistress and Safia’s elder sister offers to make her a maid, but quickly withdraws that offer too. When Chandni’s jewels are stolen, she is virtually penniless and, left with nowhere to turn to, calls up Qambar.

An unexpected twist to events – destiny runs as a powerful force – throws up questions of Red Rose’s ownership. Who is the rightful claimant?

As the years pass, walls are built around Munshiji’s temple and the private mosque. A new India emerges, one where saffron flags flutter in the evening breeze. What is unchanged though is an India where Muslim bards sing the epic of Alha and Udal and the Shah Madar who “went east to Ayodhya/the city of Lord Ram’s avatar”. What is unchanged is the idea of a syncretic faith, where at the urs at Bahraich, the sick and the blind, Muslim and Hindu, poor and rich arrive seeking benediction.

Hyder’s craft as a natural storyteller made her an unparalleled writer in the world of Urdu literature, and in Chandni Begum, she summons all the gifts at her disposal – it struck me that if this was made into a television serial, it would run for years without flagging.

In translating this wonderful work from Urdu to English, medieval historian Saleem Kidwai has done remarkable service in making the world of Chandni Begum accessible to a wider readership. In an India where lines between ‘us’ and ‘them’ become more rigid, it seems all the more compelling to peek into this world, not because it no longer exists but because we are becoming increasingly loathe to hear each other’s stories.

When Hyder died in 2007 at the age of 80, the new India she hints about in her last novel had already taken root and it had been 18 years since she had written Chandni Begum.

Ultimately, the idea of land and its ownership is summed up in one simple sentence in the novel. Who has the greater claim? Whose is the older right?

Remarks one of the characters: “A million years ago, there was an ocean here.” The soil, like the other elements, is beyond possession and ownership. This is the universal, enduring truth.

Namita Bhandare is a Delhi-based journalist who writes frequently on gender issues confronting India.