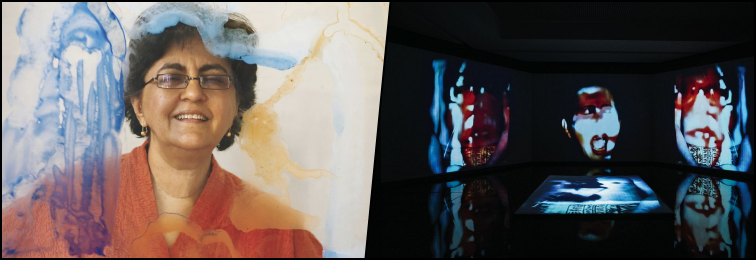

In conversation with Nalini Malani, one of India’s foremost contemporary feminist artists, about the influences that have informed her work, what it was like being a woman artist in the ’70s and more.

The Centre Pompidou in Paris, one of the world’s leading museums of modern and contemporary art, is holding a retrospective on the feminist Indian artist Nalini Malani titled ‘The Rebellion of the Dead, Retrospective 1969-2018,’ which will run from October 18 to January 8.

Malani was born in Karachi in 1946. Her family lived in Kolkata before moving to Mumbai. Women’s place in society, the rise of fundamentalism and ecological destruction are some of the recurring themes of her work. She was one of the first Indian artists to use video in the early 1990s.

This is a first retrospective at the prestigious museum dedicated wholly to an Indian artist. In 1985 and 1986, several Indian artists’ works were shown at the museum. More recently, in 2011, an exhibition called ‘Paris-Delhi-Bombay‘ brought together works of several Indian and French artists.

Malani spoke to The Wire in Paris, tracing her journey and discussing the influences that have informed her work.

Excerpts:

On the two walls flanking the entrance to your retrospective, you, in situ, have made what you call a Wall Drawing/Erasure Performance, something you’ve been doing for the last 25 years. You make these large wall drawings and have them erased by different people. This is to emphasise the ephemeral in our culture and also to pay tribute to Jaipur’s fresco artists whose works were being destroyed due to negligence. All this against the backdrop of the rise of religious fundamentalism.

Indeed, these Wall Drawing/Erasure Performances became over the decades a characteristic manner of my work. In the case of Centre Pompidou, the work is called Traces and it is made in two layers of drawings, with two different materials, from which one remains and the other will progressively disappear over the exhibition period. This Erasure Performance is done by people who are working at the Centre Pompidou. In Lausanne in 2010, I had announced a performance, but the Swiss audience was quite surprised when they heard that they would be the performers themselves, and were taken aback with the idea of “defacing” a museum wall. Initially hesitant, they overcame their shyness and even started drawing with their erasers with the remains of the charcoal. In India at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in 2014, I asked the guards – who had carefully protected the drawings for months – to erase the larger than life female nude Medea. A clash of interest and gender that was not overcome easily.

For many artists, it’s a constant tussle between preserving the meaning of their work and their saleability in the marketplace.

Selling the work is of no interest to me, but what is important is that people see it. Without my audience, the art does not come alive. When in the past I could not afford a studio, I moved in with my mother, but I did not compromise to make ‘consumer-market-oriented’ work. Also, I am rather pleased to know that hardly anybody is throwing my works into auctions.

Would it be correct to say that the political urgency in your work is often set in a feminine framework?

Well, if we don’t listen to the voice of the female instinct within oneself (this applies to both men and women), I think we are doomed. It’s important for those who wield power (mostly men) to act now, and that’s what the cry is about.

The centrepiece of the exhibition here is Remembering Mad Meg (2007-2017). It is in your unique signature style of video/shadow play. Even though it’s bright and lucid, the subtext is disturbing. We even hear a woman shrieking.

This video/shadow play is based on the 16th-century painting Mad Meg by Bruegel the Elder. In my interpretation, this female protagonist tries with her army to get rid of the evil of the land. It is a fairly small painting, where Meg dwarfs the rest of the figures and she is immersed within this endless battlefield with explosions, fire and mutated figures.

For me, today, male capitalism takes on the main stage in a manner that it is not a good prospect for the earth itself. That is why I refer to a 1954 essay by Hannah Arendt where she says the earth is the very quintessence of the human condition. The idea was that it is finally the voice of the woman that will count.

You make an appeal against sectarian violence through some of your works. And it’s often through women’s voices again. In Hamletmachine (2000), we hear a Muslim woman crying out in Hindi “We are all brothers and sisters. How long will you keep up this hostility?” In Unity and Diversity (2003), there are references to the violence in Gujarat in 2002.

Women were very badly hurt at that time. There were even cases of pregnant women being raped. What is it that is so harmful to you that you want to go to that extent to annihilate a woman who is pregnant? What is it in the human mind that drives us to this? Those are my questions.

For Unity and Diversity, the starting point was Galaxy of Musicians by Raja Ravi Varma, an academic painting of 11 women in 11 different costumes of India, playing different instruments in harmony. At the end of this single-channel video play, there is the destruction and women have to resort to taking up arms, not only in India but in other parts of the world as well, because they had to defend themselves in some manner.

This retrospective will be in two parts and will represent 50 years of your work. The first, here at the Centre Pompidou and the second will be in Castello di Rivoli, Italy next year. How did your journey begin?

We were refugees from Karachi. When I told my parents I wanted to study art, for my father there was no such thing as a “female artist” and he was very much against that. I was an only child and he used to say I needed to have a degree in order to get work. So I proposed I’ll do medical training at art school, but it was very tough to convince him. Five years I was at the Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay where they taught anatomy and they even took you to post-mortems to study cadavers. Later on, I was lucky to work with two magazines, Dharmyug and Sarika, which were publishing the new post-independence writers for which I made illustrations.

But then your work was shown at Pundole Art Gallery. You were just 20.

In fact, this first show that I had was as a student, which was seen as a very brattish thing to do. I did very overt kind of psychological, angsty and sexual paintings. I was very patronisingly told, “Beta, this is the time to get married. Why are you doing all this?”

Alleyway, Lohar Chawl (1991) was your first installation, exhibited in Jehangir Art Gallery in Bombay. It refers to the wholesale market area where you had your studio from 1977 to 2003.

This was indeed my first installation, where I made it a point that the public became part of it, by walking through it. As such they would be surrounded and rubbing shoulders with what one could encounter in a shady lane. This I presented in the gallery in a very bourgeois area of south Bombay.

You were a pioneer as a woman working with new media in India in the late 1960s. Your films were quite clearly feminist. For your film Onanism, you filmed a woman on a bed, where her body was swept by spasms with a sheet between her thighs. Female sexuality was a taboo subject. Later in 1973, you made the film Taboo.

When Mani Kaul was making Duvidha, which was a feature film, I was doing continuity for him. I was meeting the weaver community. In Rajasthan, each community has their own draft for weaving depending on what caste they are. The women do all the spinning and making of the cotton into thread and filling the bobbins etc. but they were not allowed to weave and for them to touch the loom was a taboo.

The retrospective taking place in Paris makes all the more sense given that you spent your formative years here.

I studied in Paris from 1970 to 1972, this period became like the university of my life. With my friend Jyotsna Saksena we followed lectures by people like Noam Chomsky and Claude Levi-Strauss and attended public initiatives started by Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Along with this, I met filmmakers like Alain Resnais, Jean-Luc Godard and Chris Marker, which validated for me that the medium of the film went beyond entertainment but was a tool of cultural and political criticism.

At the same time in Paris you made a series of papier-mache heads, one of which is displayed at the Centre Pompidou.

The stories and newspaper images of the atrocities of the Bangladesh liberation were such that I could not absorb this into a medium of art that was familiar. The very basis of the printed matter became the basis, and as such, I welded the magazine and newspaper pages into water with glue to make these fragile sculptures. All five that I made I offered for an auction to collect money for Bangladesh for the liberation army.

In the ’70s, you had strong affinities to feminist artists such as Nancy Spero and Ana Mendieta in the US. What was the scenario in India at that time and how was it to be a woman artist then?

Engagement in politics was there among artists in India. But some leftist male artists would almost resent my talking feminism with their wives.

After I visited A.I.R (Artists in residence) in 1979 I was inspired to start something of this nature in India and I put together a list of 17-18 Indian women artists so we would together have a show. Even with the help of Pilloo Pochkhanawalla, in a period of seven years we were not able to find the basic funding for this project, as no institute in India believed in the need of making an exhibition and catalogue about female art. Finally, it was as a group of four – Arpita Singh, Nilima Sheikh, Madhvi Parekh and myself – that we got our first exhibition in 1986 and our first catalogue in 1987, invited by Swaminathan in Bhopal. It will be very surprising to know that we approached a woman critic to write for the catalogue, who rejected this unique chance, and it was finally Ashish Rajadhakshya who wrote the essay for our traveling show. It was like that at that time.

Someone who claims to empathise with the cause of women told me recently that feminism has failed because we are still struggling with the same things. How would you respond to that?

Was it a man or a woman?

A man.

There you are. No, feminism has not failed. Not at all. We have done very well. So many of us have agency today. But I really think this is the last straw. I believe what we are seeing is the last battle and the ground will be taken away from under their feet.

Noopur Tiwari is an independent journalist based in Europe.