On June 2, the Pune Pride Committee, set up by the Sampathik Trust, organised the city’s ninth pride march.

Kickstarting this year’s pride month, the walk began from Sambhaji Park covering Cafe Goodluck Square, Fergusson College road, and culminated at the park around 12:30pm.

Bustling with 800 participants, the pride walk came with a list of rules which were updated on the walk’s Facebook event page:

“Requesting participants to cover their breasts and private parts while dressing. Any political party/caste/ religion/ history character based banners, flags, hoarding, shouting, slogans will not be entertained. Indradhanu Pune pride committee holds all the final rights of pulling down any objectionable content, if observed during the pride walk.”

I talked to a few participants, allies, and members of the community to get an insight into this rule and what it might imply for the politics of the LGBTQ+ community.

Divided opinion on the rule

Sarang Punekar, a transgender person, who was attending the Pune Pride for the third time, when asked about the rule, called it a “manifestation of the patriarchal grip we are controlled by.”

Punekar added: “if I want to wear a bikini I should be able to, but that won’t happen here because of the patriarchal rules and regulations that govern the space of the pride.”

They said they want to scream, “we want freedom!” like Kanhaiya Kumar but the pride is limited to slogans like “I am gay, that’s okay,” “I am Hijra, that’s okay”.

Pune Pride March 2019. Image credit: Shubhangani Jain.

According to a gay man, Abhilash, the rule of not bringing your caste/religion/community into the pride movement means making the space of the pride free of conflicts arising out of tensions on communal or caste lines.

Abhilash extended his gratitude to the Supreme Court for striking down Section 377 last year and said that for him, pride means being able to express their feelings and identities in the public with people they call their own.

When I asked him about the rule that might hinder this freedom of expression, he stressed on avoiding ideological conflicts that might come up if the participants wear their caste and religious identities on their sleeves.

“We [the community] are also discriminated against caste and class lines but why should we bring it here (pride)?,” he asked. The focus is on the stigma and discrimination faced by the community.

Also read: A Queer Take on the Idea of ‘Pride’ in India

Alka Pawangadkar, the coordinator of Stree Mukti Sanghatna, who was attending the Pune Pride for the third time, came to extend her solidarity to those “who need recognition, support, and strength”.

Regarding the rule, she said, she’d have liked to see people from different communities speaking various languages “exhibit” their identities through banners and slogans so that society understands that the community is very much part of it.

When I asked her about bringing in intersectionality into our prides like we do in women’s movements, she says, “Othering is so easy and these are toddler steps for the community,” which – with course of time – they will pay heed to.

Not the first time

In 2017, Samapathik Trust’s founder, Bindumadhav Khire put up similar rules inviting immense backlash from people, who went as far as boycotting the pride. The rule mentioned on the Facebook event page said, “NO Dhol-Tasha, No Dancing! NO Political or Religious Slogans or Posters! Wear Decent Clothing Only and Behave well!”

Khire said he made the rules to save the community from embarrassment since parents of LGBTQIA+ youth will also be attending the pride.

This writer interviewed Omkar Joshi, one of the members of the Indradhanu organising committee to understand their reasons for having similar rules.

Pune Pride March 2019. Image credit: Shubhangani Jain.

Omkar, who volunteered to be part of the pride organising committee, said they didn’t have anything against any community, but that they work actively on LGBTQIA+ issues which is why they wanted to focus on them solely. “Humari community mein sabhi dharm aur jaati ke log hain, discrimination nahi hona chahiye (our community has people coming from all religions, castes. We didn’t want to discriminate against any of them)” he said.

On the rule of covering private parts, he said that adhering to societal norms of morality in clothing is important for the community too. Because parents of the LGBTQIA+ folks also attend the pride, the image of the community should be good. Omkar also mentioned how pride means bringing your sexuality into the public and keeping one’s religion and caste identities at home.

The focus is on queerness, not so much on intersectionality.

Idea of inclusivity within LGBTQIA+ community

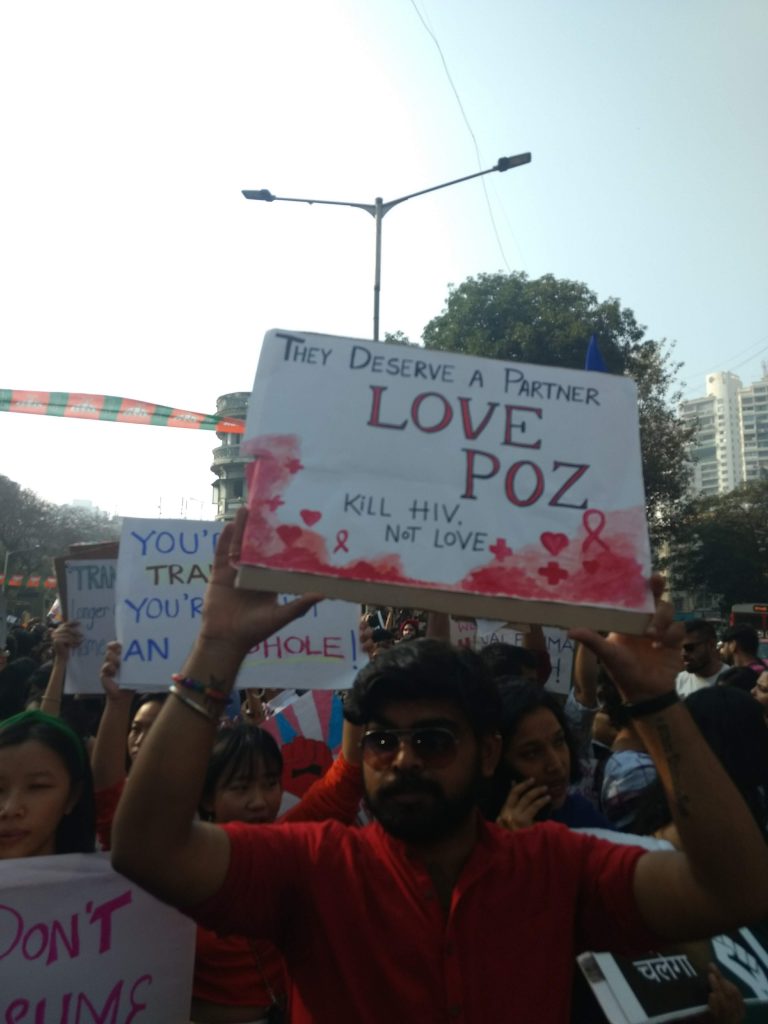

I went to the Mumbai Pride earlier this year and observed some differences. People held banners of being pansexual, asexual, queer Muslim, Dalit queer, among others.

A variety of slogans echoed like, “Rohith tere sapnon ko hum mazil tak pahuchaayenge! (Rohith, we’ll make your dream come true!),” “Don’t Assume Your Kids are Straight!” and so on. The space was coloured, like the rainbow, in hues of difference which came together in a space of pride.

Also read: Mumbai Pride 2019: The Revolution is Here, And it’s Rainbow and Intersectional

I write this not to compare or criticise the Pune Pride, because every pride – in being a political resistance to a violently heteronormative society – is also marked by the socio-political current of the city in which it takes place.

This makes me probe the question of how diversity, inclusion, intersectionality and our varied understandings of them manifest in pride marches across the world.

Now that heterosexual men are planning to organise a “straight pride parade” in Boston, and our vocabulary of queerness has expanded, this question seems to have some bearing.

It is interesting to note how the space of the pride that is itself segregated on various class, gender, caste and religious markers becomes a whole that sometimes represents and reproduces these very markers under the banner of diversity and inclusivity.

Shubhangani Jain is in her final year of masters studying gender/power. She is a pop-culture and panipuri enthusiast.

Featured image credit: Twitter