Delhi University Students’ Union (DUSU) elections are a mega-event, to say the least. They involve SUVs and convertibles sports cars with men in sunglasses and saffron scarfs hanging out the windows or sitting on the roof. They involve big billboards with oddly spelt names on every corner of campus and thousands of small paper pamphlets littered across streets.

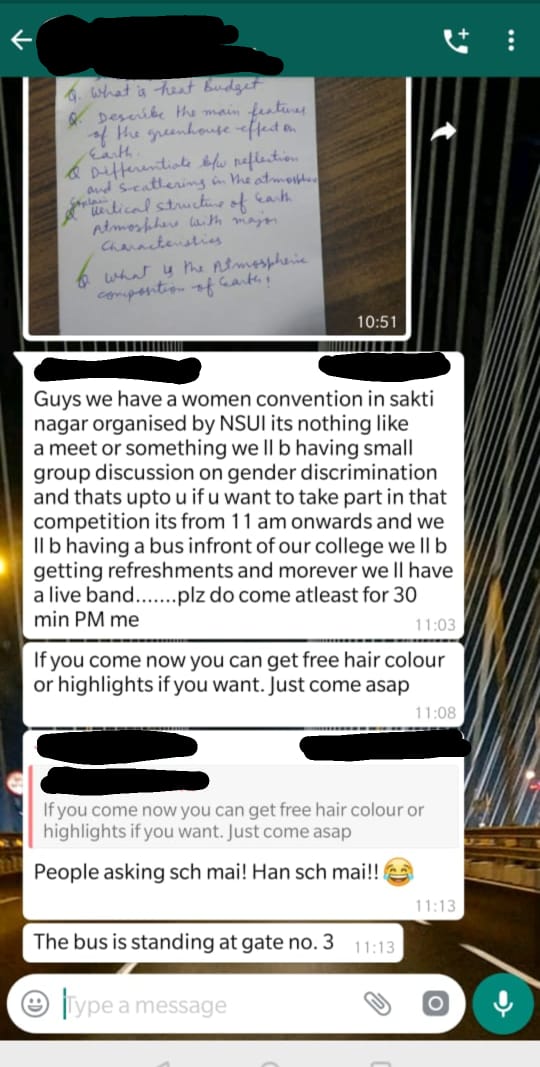

WhatsApp groups are flooded with invites to trips and promises of free goodies, mainly by the student wings of the two major political parties in India – Akhil Bhartiya Vidya Parishad (ABVP), the right-wing student vertical of the BJP and National Students Union of India (NSUI), the student body of Congress. Apart from them are the left-leaning parties such as All India Student’s Association (AISA), Student’s Federation of India (SFI), etc.

An example of how student parties try to induce students into voting for them. Credit: Ritul Madhukhar.

A major part of the ‘democratic’ process of DUSU elections is manifesto reading.

Throughout August and early September students are greeted, and sometimes disrupted, during class with candidates wishing to speak to us informally about the upcoming elections. However, manifesto readings are a formal way for candidates and representatives to put forth their ideas and respond to questions regarding the same.

On September 9, a whole chunk of the day was cleared from Miranda House’s daily schedule to accommodate the manifesto reading. The event started with Miranda House Students Union (MHSU) candidates’ speeches. This year turned a new chapter for MHSU since the college saw a surge in the number of candidates contesting for each post, in contrast to last year when the president’s position went uncontested and there was a single candidate for vice president.

Around 2:30 pm the DUSU candidates were given the podium to speak, starting with ABVP’s vice-presidential candidate, Pradeep Tanwar. However, he was immediately met with chants of “ABVP, go back!” from the entire auditorium. Students stood on chairs and continued their slogans over the party’s attempts to speak. This went on for over seven minutes, post which they ultimately gave up on trying to address the students and left after showing their ballot number. This was immediately followed by friction between the ABVP members in Miranda House and the other students opposing the party where claims of curbing their freedom of speech were made from the party’s side.

This is how Miranda house welcomed ABVP. Glad to see that leading colleges in the country recognise the hooliganism and blatant violation of laws by ABVP members. ABVP is nothing but an avenue for state-sponsored violence, communalism and jignoism. pic.twitter.com/ll5xXDoRb7

— Kabir (@Mumbaichamulgaa) September 9, 2019

This isn’t the first time Miranda House students have not allowed ABVP to speak during the manifesto reading. Last year, a smaller group of people raised slogans against the party, accusing them of allegedly ignoring sexual harassment cases against their candidates. Resultantly, the party had to leave without addressing the audience.

This year, the push-back from Miranda House was bigger.

This was presumably on the grounds of the party’s history of enticing violence on campus. Yogit Rathi – ABVP’s candidate standing for the post of secretary – is allegedly responsible for the 2017 violence in Ramjas College. Last month, ABVP disrupted a screening of Anand Patwardhan’s documentary Ram ke Naam at Ambedkar University (Kashmere Gate campus) and damaged college property.

Another, more important reason for this response from the students was that ABVP members had disrupted Tempest 2019, the Annual Cultural Fest of Miranda House. Men from the party had banged and pushed on the college gates, demanding entry in lieu of Hindu College’s V-Tree protest which was on the same day in February as the fest.

Campus streets littered with fliers for DUSU election candidates. Credit: Giitanjali

A student from Miranda House, who wishes to remain anonymous shared her views on the matter, “I think the immediate slogans happened for a specific reason – Tempest security was compromised because of them. They are the reason a lot of us have stopped attending our own fest. ABVP constantly uses the front of freedom of speech but they only deserve a platform in democratic spaces when they respect that process. From the use of violence, constant harassment plus the lack of accountability they’ve shown over the years I don’t think they do. Instead, they use the manifesto reading as a way to speak a sanitised version of themselves different from their rallies and their behaviour as a party. They can’t claim freedom of speech when they constantly create a culture of fear, violence and harassment.”

Muskan Dhar, a third-year History student pointed out that they were given the time to speak. “One of the ABVP women from Miranda House was standing for the post of the central councillor. She was speaking and we even counter-questioned her when she said she supported the installation of the Savarkar bust. She went on to say that India is a Hindu Rashtra and this land belongs to Hindus! She said that in our college and was received beautifully.”

Following ABVP’s exit from the auditorium, AISA took the stage and was received with cheers from Miranda House.

While they were allowed to address the students, they were not without issues. Students claimed that they just took the anti-ABVP stand; their manifesto mainly consisted of what ABVP does wrong, rather than what they want to do right. The questions raised to them were also not answered satisfactorily.

“I asked the previous year’s AISA Presidential Candidate why he did not talk about the need for an anti-discrimination cell when he talked about internal complaint committees in his speech at Miranda House. Why a manifesto that talks about gender justice so conveniently ignores social justice. He said that they have this issue in their demands and he will bring it forward. This year also, the presidential candidate from AISA did not talk about the issue that AISA said they will raise. So, I question the hypocrisy of the student’s organisation,” said Tejaswini Tabhane, an Economics student at Miranda House.

DUSU elections are somewhat of an inconvenience to most students – something to be endured and avoided until it’s over. I take rickshaws instead of walking because it’s not safe during election season. But taking a rickshaw means leaving 15 minutes earlier because the Arts Faculty road is bound to be log-jammed.

Miranda House is a safe space for its students. For the most part, it shelters us from what goes on outside. Manifesto readings are one of the few times outsiders come into our little bubble. Today’s response to ABVP is a reassurance that everyone we share this space with stands together to oppose what we know is wrong.

Featured image credit: Ritul Madhukar