For much of the English-speaking world, the term “triangular trade” refers to one thing only: the transatlantic slave trade. Many school history books feature maps with arrows linking Europe, Africa and the Americas, with mind-boggling figures and icons representing the commodities exchanged.

From the perspective of Britain, France and the Netherlands, “triangular trade” is an apt descriptor. But from the perspective of Brazil, Cuba and others, the term has much less validity. When the European powers abolished their slave trades, merchants in the Americas built on many years of experience in their own bilateral trades to keep it going.

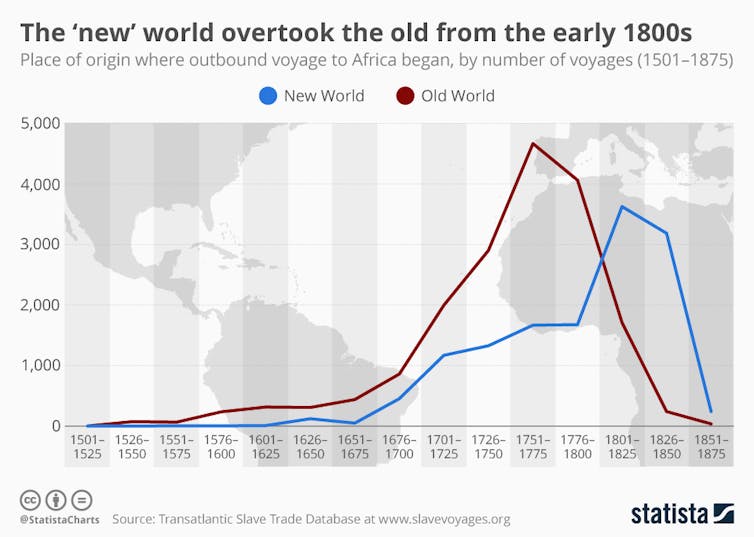

According to the latest figures from Voyages: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, an authoritative source which contains information on over 80% of all slaving voyages, nearly 40% of all enslaved Africans arrived in the Americas aboard vessels that had sailed to Africa directly from New World ports. That means that almost two-fifths of the entire slave trade traced a bilateral, rather than a triangular pattern.

So there was no single “transatlantic slave trade”. And this makes it very difficult to generalise about the slave trade. Understanding this dimension also underscores the global nature of the trade, which was organised by merchant networks spanning not only the Atlantic but also the Indian Ocean.

Brazil’s trades

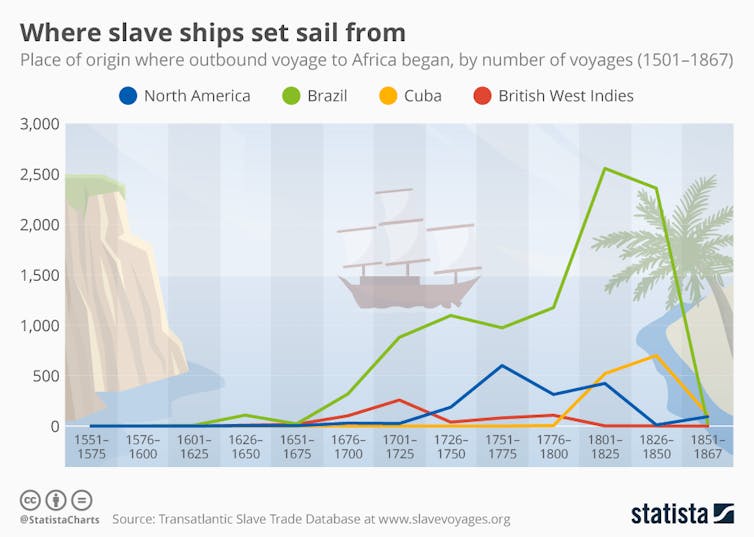

By far, the most important of the bilateral traders was Brazil. This is hardly surprising, since Brazil imported more captives than any other New World region, receiving just under half of all of the Africans transported across the Atlantic. While many of these Africans arrived aboard vessels sailing from Portugal, the vast majority – perhaps nine in ten – came aboard vessels that had originally sailed from Brazil. Merchants in Brazil began trading in earnest in the 1630s, when parts of the colony were occupied by the Dutch, but increased participation dramatically after the Dutch expulsion in 1654.

After British abolition in 1807, Britain went on a crusade to get other countries to end the slave trade, pressuring them to sign treaties. But Brazil’s ability to supply its own market for captives helped it to resist British pressure to stop slave trading – even after Brazil, which declared independence from Portugal in 1822, formally renounced slave trading in 1830.

Brazilians managed to do this by trading their plantation surpluses for slaves in Africa. The most important of these was cachaça, the Brazilian sugarcane spirit, but tobacco also played a key role, along with gold. Traders supplemented these goods with Indian textiles, which they obtained via the global Portuguese mercantile networks, and with sophisticated financial instruments that allowed them to transfer credits around the globe.

Portuguese-Brazilian merchants in south Atlantic ports such as Luanda in Angola played a key role in assembling trade goods and procuring captives, which they often shipped on freight to Brazil. Unlike the north Atlantic model, in which the organisers of a voyage owned the vessel, the trade goods, and captives, Brazilian traders were often shipowners whose vessels carried captives as freight for multiple owners from Africa to Brazil.

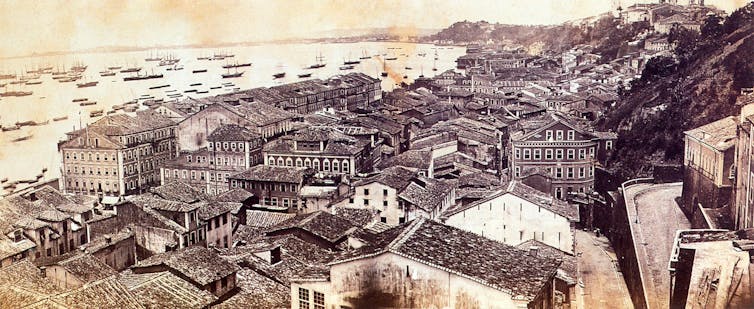

The port of Salvador in Bahia. Only Liverpool dispatched more slaving vessels. Credit: Guilherme Gaensly (1843-1928), via Wikimedia Commons

Caribbean merchants build their own trade

Although Brazil was by far the largest bilateral slave trading power, it was not alone. As my own ongoing research is showing, merchants in the British Caribbean, Barbados especially, also participated, although at much lower levels. Their trade was concentrated in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, motivated by the chronic inability of the Royal African Company, the British slave trading monopoly, to deliver enslaved African labourers in the numbers they desired.

Like the Brazilians, British Caribbean merchants monetised their plantation produce in the form of rum and traded it for captives. And like the Brazilians, they supplemented their rum cargoes with textiles, British woollens more than Indian cottons.

Merchants in the New England colonies, principally Newport, Rhode Island and Boston, Massachusetts, began a similar trade. Theirs was unique in that it ran in triangular fashion from New England, to Africa, to the Americas – the only New World-based trade to do so. During the colonial period, most of these captives were taken to the British Caribbean, but after independence in 1776 Americans supplied captives to their own markets, as well as to Cuba.

As a slave-trading power in its own right, the Spanish colony of Cuba was a latecomer. Large-scale plantation slavery only emerged there in the second half of the 18th century. Few there had any experience slave trading, largely because the British and Americans supplied most of the captives. However, when those two nations abolished their slave trades in 1807-8, Cuban traders became more involved. For a few years they served an apprenticeship of sorts, then began operating their own slave trade, establishing commercial connections on the African coast. Like the other traders, they exchanged cane spirits and tobacco for captives, but also British textiles and manufactures, and even some silver.

After 1820, all of this was illegal under an Anglo-Spanish treaty, in which Spain committed to ending its slave trade, but by then merchants had created a multinational, polyglot network of traders, bankers, shipbuilders and traders that operated illegally. This network operated for four more decades before finally succumbing in the 1860s.

The common denominator in all of these trades was an ability for these colonies to turn slave-grown plantation produce into goods that were exchanged for captive slaves. Cane spirits – rum, cachaça, aguardiente – was the backbone for most, but tobacco figured in some of them. All but the Americans supplemented these goods with manufactured products, textiles for the most part. Most of these came from Asia via trade networks that extended into the Indian Ocean, but Britain was also a major source, especially in the 19th century.

Even when restricted to the British, French and Dutch trades, the term “triangular trade” conveys the false impression that it was a closed system. In reality, the slave trade was a vast enterprise, assembling goods from across the globe, exporting and re-exporting them to Africa for captives who were then carried to the New World to labour at a variety of tasks. Geometry doesn’t even begin to capture it.

Sean Kelley, Senior Lecturer in Global History, University of Essex.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.