Deepak Bhojwani, former Indian ambassador to Colombia, discusses the factors that led to the No camp’s victory, the implications of the vote and the path ahead for the country.

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos (L) and Marxist rebel leader Rodrigo Londono (R), better known by the nom de guerre Timochenko, shake hands after signing an accord ending a half-century war that killed a quarter of a million people in Cartagena, Colombia September 26, 2016. Credit: Reuters

On October 2, Colombians narrowly rejected a peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), in the surprise culmination of a process that sought to end a 52-year civil war. For four years, the government of President Juan Manuel Santos held negotiations with Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri, the leader of the FARC who is better known by his nom de guerre Timochenko, to bring to a close a painful chapter in the country’s history, in which 220,000 people have lost their lives and millions have been displaced.

The pact was agreed in August, and Santos and Timochenko signed it at a ceremony in Cartagena on September 26. Many, including former President Alvaro Uribe, were critical of the pact for being too lenient on the FARC rebels by allowing them to re-integrate into society, form a political party and escape jail sentences. During the referendum, Colombians were asked to respond to one question – do you support the final agreement to end the conflict and the construction of a stable and durable peace? – with a yes or no answer. Ahead of the vote, most opinion polls gave the Yes camp a comfortable majority and expected the deal to be ratified easily.

The No camp won by 50.21% to 49.78%, plunging the peace process into some uncertainty, although Santos and Timochenko have reaffirmed the commitment of both sides to attaining peace.

In an interview with The Wire, Deepak Bhojwani, former Indian ambassador to Colombia, discusses the factors that lead to the No camp’s victory, the implications of the vote and the path ahead for the country.

Deepak Bhojwani, former Indian ambassador to Colombia. Credit: LinkedIn

Why did the Colombian people vote No in the referendum on the peace deal? This despite everyone thinking the result was a given.

I was in Colombia till September 12 for almost three months and when I came away I was convinced it would be a Yes vote. I suspect most Colombians who wanted peace were also so convinced [that the outcome would be Yes] that there was a tremendous amount of abstention.

There were also some political events which provoked the right wing, in particular and President Alvaro Uribe’s party Centro Democrático, which was the vanguard of the No campaign. These included the non-election of Attorney General Alejandro Ordonez, a notorious right winger, campaign for gay rights, etc. There were other political issues, including the lack of visible support for the peace deal from Vice President Germán Vargas Lleras. He kept a very low profile during the entire negotiations, but belatedly came onboard and declared his support.

There were also certain issues on the justice front regarding reparations and punishments or sanctions on FARC. This was partly the reason. Of course no one will know the full reason because it has been less than 24 hours, and I can’t claim that I know better than people who may have a better idea eventually, but I think these were largely the reasons.

The deal was publicised and garnered support from all quarters, yet the voter turnout was only 37%. What explains the low turnout? Was voter turnout low in different parts of the country and is there is any pattern?

Low voter turnout made a difference, and also certain features of the campaign and of the political process which strengthened the right and the No campaign. I say right in a very broad sense as its Uribe who is behind it.

What happened also was that there was a tremendous buildup of expectations and thus disappointment. For instance, over the financial aspect of the deal. The people were asking questions like if the FARC really had any money from what it had stolen. A few months ago, the group declared that they didn’t have any money at all. Also, the deal, which I read through, promised a tremendous amount of financial support for the FARC cadres and leaders. So, there was going to be a huge expenditure on getting peace in place. This also may have played on the people’s mind.

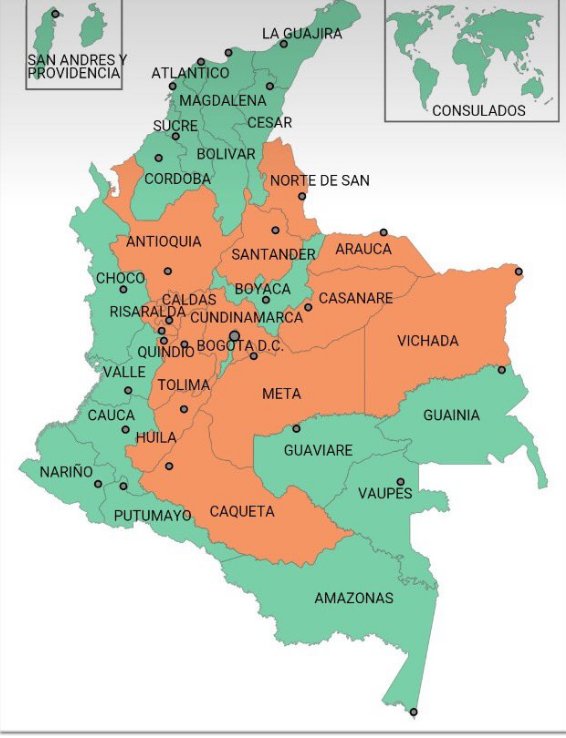

Apart from the 37% voter turnout, the No camp won by about 54,000 votes. In certain populated areas in the periphery, the Yes did much better, but in the centre of the country, particularly Medellin, where Uribe’s party is located, they did very poorly. In most parts of the centre, which is heavily populated and richer than other parts of the country, there was a resounding No vote. But in Bogota and the state of Boyaca, a significant number of people voted for the deal. The narrow margin shows that it was touch and go, and the low voter turnout added to that.

So is it safe to say that this perhaps is just a reflection that the people wanted a better deal?

Clearly. In the case of the No, what I can definitely say is that there was conviction. In the case of the Yes, there was also conviction, but there was a considerable amount of apprehension and apathy, because a lot of those who should have voted Yes either did not go to vote or felt that it made no difference. Now that it is staring them in the face, there will be a lot of introspection.

Another thing to remember is that it is not an easy matter for most Colombians to decide which way to vote. It has been an agonising process and to come to terms with groups like the FARC is very difficult.

Many people have been affected by violence perpetrated by the FARC…

Exactly. Its almost a priori on the part of lots of advocates of the vote but on the parts of the citizens, there is a considerable amount of apprehension.

It is important to mention here that during his presidency, Uribe held referendums on 15 reforms in 2003. He lost almost all of them, because although he had a resounding Yes vote, none of them came to the 25% threshold required. In the case of the peace deal plebiscite, the constitutional court established a 13% threshold, which was reached, but it was not the majority.

A supporter of the Yes vote cries after the nation voted No in a referendum on a peace deal between the government and FARC rebels, at Bolivar Square in Bogota, Colombia, October 2, 2016. Credit: Reuters

What are the implications of the vote?

What happens next is that President Santos has declared that he is going to seek peace until the last day of his mandate. Timochenko (the FARC leader) has said they are for peace. In fact, he used the term ‘political movement’, which means he defines the FARC not as a guerilla group but a political movement. It is all the more incumbent upon the FARC as a political movement to seek peace through institutional processes. This is being taken to mean by the Colombian media that the bilateral ceasefire will continue, and there will not be war.

One of the reasons for the vote on the No side was because, at some point the advocates, including Santos, said that if there was no approval, it would mean a return to war. This was seen as a form of blackmail and a lot of people did not like that. Now Santos has come around very openly and said that they will go back to the drawing board. In fact, he is sending his negotiators and several members of his team back to Havana almost immediately to try and see if they can renegotiate the deal, as I understand from reliable media reports.

On the other hand, Uribe has also said – and this is a good sign – that they are not going to continue to be naysayers, which means that their ‘no’ is changing to a ‘yes, but’. In fact, this has been their continuous refrain – that they are not against the deal – that they are against this deal which gives away too much. Uribe claims it legitimises what the FARC has done in a certain way; it gives them virtual impunity; it imposes a severe burden on the taxpayer, which is just not acceptable. He wants the private sector to be promoted, he wants more austerity and he wants of course basically that there should be institutional justice. So he says with all these caveats they [the No camp] are willing to go for a new deal.

The deal will probably have to be refashioned. But there is another aspect that is important. When the constitutional court gave its approval for the plebiscite – incidentally it was not legally binding for Santos to go for a plebiscite – it said that in the event of a No vote there could be another deal, even with different players, put to another plebiscite.

With the No vote, what we have is a possibility of further negotiation and another accord, and there is no ruling out that there could be another plebiscite. Santos wants to hold an all party meeting at the earliest to see if he can reach at some political agreement. It is anybody’s guess whether that political agreement will come about. Perhaps they will decide against holding another plebiscite, which would also cost money and take a lot of effort, and also bring out a lot of aggravation publicly.

If they reach some sort of understanding in the all party meet, is Santos compelled to go back to negotiation with the FARC, or is there any other way to go forward?

Of course. Let me put it this way: there are several contentious issues. For instance the question of impunity and what will the FARC have to serve in terms of jail time. First of all, only those FARC members who do not surrender and accept the peace deal will be tried and sanctioned under the normal system. So those who do surrender and accept the deal, no matter how egregious their crime, as I understand it and as most Colombians have understood it, will be under virtual house arrest. Only those who have committed serious human rights violations will be the exception, but these will perhaps number very few. Now a lot of Colombians believe this is unacceptable.

If you have to renegotiate, since one of the main points of the opposition has been to question the judicial impunity – the FARC cadres have slaughtered people and have killed children, how can they possibly simply be given a slap on the wrist – all these aspects have to be renegotiated.

It will not be possible to go back with the same text, which means there is no way that Santos can go into an all party meeting, particularly having lost the plebiscite, and say ‘give me a yes or a no’. He will obviously have to go back to the negotiating table and this is why he is sending his negotiators back to Havana.

Did the vote become a referendum on Santos, whose approval ratings have been extremely low?

Not exactly, but to a large extent, he has put his political reputation on the line. Throughout his mandate, he has been going against what has been considered his mentor Uribe’s line. As Uribe’s defence minister, Santos had taken a hard line and was responsible for the decimation of FARC cadres. Then he started talking peace in 2012. This means he made a conscious decision. He was confident that he had a reasonable deal, which included a lot of factors that he thought were essential and which the FARC had to give in on. By calling for a plebiscite, he felt that not only would he be ratifying the peace deal through the people of Colombia, he would also be showing his opposition and the world – he wanted backing domestically and internationally. He got the international backing almost immediately.

One of his biggest mistakes in my opinion was that he was far too ostentatious. Two months ago, when he had the ceasefire deal, which was widely publicised, he got many world leaders to attend. Then a few weeks ago the signing in Havana with Timichenko again was a very ostentatious affair with many from the international community attending. Then the signing of the deal in Cartagena. There was emphasis on the fact that Colombia would finally have peace. He was so confident. So you could say that to some extent he was responsible for being a little over-confident though his approval ratings were already extremely low because he was doing things which to even moderate Colombians had gone beyond the pale. But he felt, perhaps rightly so and we cannot judge him, that peace is essential even if they had to make sacrifices. In that sense, I would say that he was an unfortunate victim of the confidence and determination that he displayed. But he may well still prevail.

Santos had announced that perpetrators of atrocities on both sides would be brought to justice. And a day ahead of the vote the FARC announced that they would pay reparations to victims of the conflict out of the group’s assets. But many people, including Uribe, have argued that the deal was too lenient on the FARC. In your opinion, was the deal too much in favour of the rebels?

I missed the FARC’s announcement, but if that is true then it puts a different complexion on what the FARC has been saying; also it would have been a very positive feature. But perhaps the announcement came too late and the people’s minds were already made up.

Uribe always claimed that the deal was far too lenient. But there are not that many reserved seats in the parliament for FARC members. To have any significant position or power, they would have to really fight and win elections. Historically, the Left has not enjoyed parliamentary majority. They have won the city of Bogota a few times, but have now even lost that. In fact, the Polo Democrático (the Left coalition) has lost considerable ground and has got fractured in the past few years.

Colombia’s former President Alvaro Uribe gestures after the nation voted “No” in a referendum on a peace deal between the government and Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) rebels, in Rionegro, Colombia, October 2, 2016. Credit: Reuters

I cannot say the deal was too much in favor of the rebels, because that would be a subjective judgement. I am not sure how easy or difficult it would have been for Santos’s team to have got a better deal out of them. There is also some residual sympathy for certain ideas that the FARC put forward. For instance, everyone, including Uribe, has talked about social justice. This has been a blot on what is considered a very right-wing conservative regime in Colombia. The civil war has also displaced and dispossessed millions, mainly from the rural areas. There is considerable poverty, the country incidentally is about 30% the territory of India, so it is huge. The population is mostly concentrated in the North, the West and the Centre. There are many parts that are clearly very sparsely populated. There is highly unequal land distribution and much corruption. There was a need for social, and land redistribution, also to give agriculture a boost. And this was an honest demand of the FARC.

Now whether too much was given away or whether too much was promised and in fact could we even say whether the targets were really realistic, that would have remained to be seen if the plebiscite had been positive.

One feature that is very important to consider is that – according to a UN study -the area of Colombia under cocaine cultivation has expanded massively in recent years. This is an issue of concern. Would the FARC, which has committed to give up its narco-activity, have been able to collaborate with government authorities to make sure that this menace would have at least been checked if not rolled back? This could have been a very positive aspect of the entire deal and it could still be if the FARC cooperates; they claim that they are not responsible for narcotrafficking, but if they came onboard to fight it and help the government, that could be a very positive aspect of the deal.

How will the peace process move forward? What happens next?

What happens next is very critical. It is very important for us to wish Colombia well. The country is going through a tremendous economic downturn. It is not in recession, but it is growing about 2%, which is very low. The country has been very badly hit by the low oil prices and government revenue has shrunk. Colombia unfortunately has not established a very solid industrial and technical base. For a country of 48 million, these are tough times. The government has committed under the peace deal, if and when it goes through, that it will spend considerable amounts of money. Santos’s philosophy is that taxes need to be increased. Already they are talking about increasing VAT significantly and corporations in Colombia are crying hoarse saying they are the only honest taxpayers in a country with a lot of tax evasion and corruption.

Uribe’s counter to this is that the country must not increase taxes but instead must let the private sector lead the economic recovery. What happens next is not just how peace with the FARC is attained but also how economic policy is determined.

Another aspect which is also very important is what happens with negotiations with the ELN (the second largest guerilla group), which is thought to have around 3000 militants. Last year the government announced it would start talks with the ELN on condition the group release all captives in its custody. This has not yet happened. The group has recently become more active obviously to try and improve its bargaining position vis-à-vis the military and the government when talks begin. ELN is flexing its muscles and has to come next.

Besides, during the height of the conflict, the rich in Colombia hired a lot of paramilitaries and private soldiers to defend them, many of whom turned rogue. Although these groups were demobilised a few years ago, a lot of them went along with guerillas and others into organised crime, and are now called BACRIM (bandas criminales or criminal gangs). Such groups might attract some FARC cadres, particularly those who have said they will not join the peace deal. You may have a few hundred cadres who back out, you may have some others from the ELN who join such groups. So the military has formulated a doctrine for the peace process, which takes into account that they will be dealing with other organised crime groups also. There is much more to to come, but the tipping point will be if the country can do away with the FARC and launch itself on the path to peace.

Supporters of the No vote celebrate after the nation voted No in a referendum on a peace deal between the government and FARC, in Bogota, Colombia, October 2, 2016. Credit: Reuters

It has taken four years to reach a deal, which is now rejected. Is Santos compelled to adhere to the No vote?

It has been rejected, but this is not legally binding either. Of course, it would be political suicide for Santos to go ahead with the deal because it has been shown that he does not have the majority of at least the Colombians who have voted. So, technically speaking, he could have gone ahead, but I don’t think he will unless he achieves political consensus one way or another.

Will the renegotiation be an easier process or could it possibly take as long to negotiate as the original deal?

I don’t think it will take that long. I think there is far greater realism that has come to prevail upon not just the government, but even upon the opposition and the guerillas. Most telling is Uribe’s immediate remark. He is triumphant but he has also said ‘we are going from No to Yes, but…’

He sees that there is a possibility for him to come centre-stage politically. Let’s face facts, this is very important for him. One way to do it is by not standing back and saying we will wipe the FARC out, because he knows he cannot. So he would also perhaps be in favor of the deal if there is political consensus on a new formula and all that remains is for the terms to be accepted by the FARC, which hopefully they will not reject.

The FARC has come such a long way. They were ready to give up their arms this month itself, so they are unlikely to want to return to war. They now have an interest, because even Cuba, Venezuela and other countries have encouraged them to go legitimate, and they have a stake themselves. Timochenko declared that their way forward now is peace. I don’t think they would want to sabotage the process, subject of course to eventual terms being acceptable.

That’s where we will have to see if the political establishment in Colombia can come to an agreement. Santos can take the views of the different parties when going back to drawing board to draw up an acceptable agreement and come back for a plebiscite.

I don’t think this process will go on for too much longer.