New Delhi: Former Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor Raghuram Rajan on Monday warned that the central bank will have to raise policy rates eventually, asking the politicians and bureaucrats to understand that this measure is “not some anti-national activity” that will benefit foreign investors but an investment “whose greatest beneficiary is the Indian citizen”.

In a LinkedIn post, Rajan said the war against inflation is never over, noting that inflation in India is up. Central banks across the world are raising policy rates, he said, adding that the RBI will have to follow suit – although he refrained from predicting when that may be.

When it happens, he said politicians and bureaucrats should see it as “an investment in economic stability, whose greatest beneficiary is the Indian citizen”. Rajan, who is now professor of finance at Chicago University, said he had experience in battling high inflation during his term as RBI governor.

When he became RBI governor in September 2013, “India had a full blown currency crisis with the rupee having experienced free fall”, Rajan wrote, noting that inflation was at 9.5% then – it is at 6.95% now.

Also Read: As Retail Inflation Hits a High of 6.95% in March, Expect a June Policy Rate Hike

Rajan continued, “The RBI raised the repo rate from 7.25% in September 2013 to 8% to quell inflation. As inflation came down, we cut the repo rate by 150 basis points to 6.5%. We also signed on to an inflation targeting framework with the government.”

These actions, he said did not just stabilise the economy and the rupee but “also enhanced growth”, adding that between August 2013 and August 2016, inflation came down from 9.5% to 5.3% while growth picked up from 5.91% in June-August 2013 to 9.31% in June-August 2016.

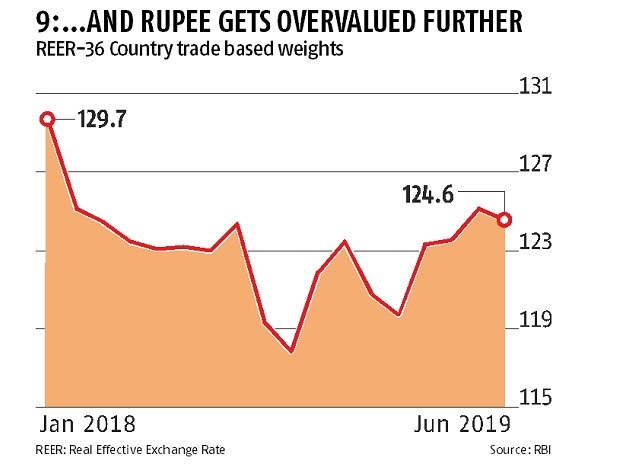

“The rupee depreciated only mildly over 3 years from 63.2 to 66.9 to the dollar. Our foreign exchange reserves rose from US $ 275 billion in September 2013 to US $ 371 billion in September 2016,” he wrote.

he said not all this was the RBl’s doing, but some clearly was. “And it was not a flash in the pan, suggesting we were laying the foundations for stability. The RBI has since maintained low inflation and low interest rates through troubling times like the demonetisation, the fall-off in growth, and the pandemic,” Rajan said.

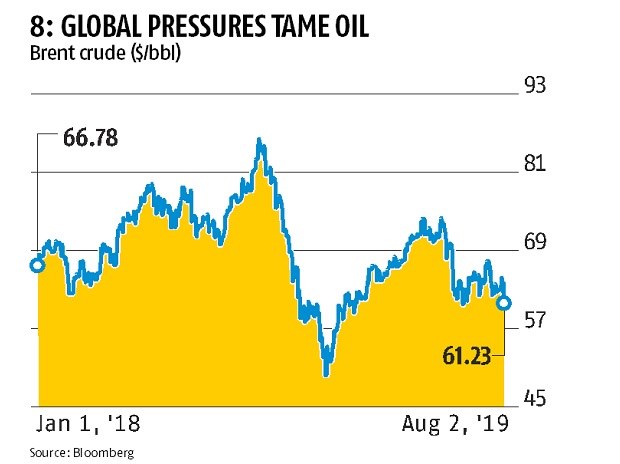

Rajan said because India has reserves of over $600 billion, the RBI has been able to calm financial markets even as oil prices have climbed – unlike in 1990-91, when the country had to approach the IMF due to higher oil prices. “The RBl’s sound economic management has helped ensure this has not

happened this time,” he said.

Saying that he and other RBI governors were criticised when rates were raised, Rajan said it “helps to let the facts talk” – and that the correct facts are important to guide future policy. “It is essential that the RBI does what it needs to, and the broader polity gives it the latitude to do so,” he said.

The full text of his post is republished below.

§

It is important to remember that the war against inflation is never over. Inflation is up in India. At some point, the RBI will have to raise rates, like the rest of the world is doing (I will refrain from trying to predict when). At such times, politicians and bureaucrats will have to understand that the rise in policy rates is not some anti-national activity benefiting foreign investors, but is an investment in economic stability, whose greatest beneficiary is the Indian citizen.

Indeed, my experience as the last RBI governor who had to fight high inflation bears this out. I became RBI governor with a three year term in September 2013 when India had a full blown currency crisis with the rupee having experienced free fall.

Inflation was at 9.5% then. The RBI raised the repo rate from 7.25% in September 2013 to 8% to quell inflation. As inflation came down, we cut the repo rate by 150 basis points to 6.5%. We also signed on to an inflation targeting framework with the government.

These actions not only helped stabilize the economy and the rupee, they also enhanced growth. Between August 2013 and August 2016, inflation came down from 9.5% to 5.3%. Growth picked up from 5.91% in June-August 2013 to 9.31% in June-August 2016. The rupee depreciated only mildly over 3 years from 63.2 to 66.9 to the dollar. Our foreign exchange reserves rose from US $ 275 billion in September 2013 to US $ 371 billion in September 2016.

Of course, not all this was the RBl’s doing, but some clearly was. And it was not a flash in the pan, suggesting we were laying the foundations for stability. The RBI has since maintained low inflation and low interest rates through troubling times like the demonetization, the fall-off in growth, and the pandemic.

Today, reserves have climbed to over $ 600 billion, allowing the RBI to calm financial markets even as oil prices have climbed. Recall that the crisis in 1990-91, when we had to approach the IMF, was precipitated by higher oil prices. The RBl’s sound economic management has helped ensure this has not

happened this time.

Of course, no one is happy when rates have to be raised. I still get brickbats from politically-motivated critics who allege the RBI held back the economy during my term. Some of my predecessors were similarly criticized. At such times, it helps to let the facts talk. And the correct facts are important to guide future policy. It is essential that the RBI does what it needs to, and the broader polity gives it the latitude to do so.