On March 8, women around the world celebrate International Women’s Day; a day they call their own when they highlight their achievements and discuss issues still unresolved. The theme for Women’s Day this year is #BreakTheBias, underscoring the idea that it is not enough to acknowledge the existence of bias; action is necessary to achieve equality.

While the rest of the world is devising strategies to improve the conditions of women, Pakistani women face the challenge of whether or not they will even be allowed to share their issues on a public forum on this day.

Since 2018, Pakistani feminists have been organising large public demonstrations for Women’s Day, dubbed the ‘Aurat March’ (using the Urdu for woman). I have attended the last four marches, – the first two in Karachi and then in Lahore – joined at different times by my aunt and daughter, friends, husband and work colleagues. This year, I am away from Pakistan and will miss marching with my comrades in arms.

As the Aurat March has grown in popularity and impact, so, too, has opposition to it. In 2020, the organisers had to obtain a court order from a Lahore court to be allowed to go ahead.

People participating in the Aurat March in 2020. Photo: Sapan News Service.

The situation has cropped up again this year, with even more vehemence.

Aurat March Lahore strongly condemns city administration

We are dismayed at the infringement of our fundamental right to march. Rest assured we will march; we have petitioned the Lahore High Court and will ensure ke march tu hoga!#AuratMarch2022#MarchTuHoga#AsalInsaal pic.twitter.com/fGEbg40kyh

— عورت مارچ لاہور – Aurat March Lahore (@AuratMarch) March 6, 2022

Pakistan’s minister for religious affairs even demanded that the country mark March 8 as ‘Hijab Day’; strange in a country where women are free to wear this headgear that is not part of the traditional garb. Moreover, there already is an annual World Hijab Day, started in 2013 and celebrated on February 1.

When women organised the first Aurat March in Karachi, no one expected such a large turnout in Pakistan’s largely patriarchal society. However, instead of the 200-300 participants expected, multitudes of women turned up at Karachi’s historic Frere Hall gardens.

It was amazing to see women from all walks of life come together to raise their voice for basic rights. The issues raised through placards and speeches included inheritance rights, the right to education, access to health services and equal wages, unpaid labour, domestic violence, demand for safety at work and in public spaces and more.

The March marked strong statement by a section of society, largely viewed as subservient and repressed.

Participants of the Aurat March holding placards bearing the issues they wished to speak against. Photo: Sapan News Service.

Many dismissed the massive turnout as a one-time fluke. However, women took it as a wake-up call to continue working on breaking barriers that have held us back in many domains. Quickly, conservatives deemed the movement as a ‘malaise, spread across Pakistan’.

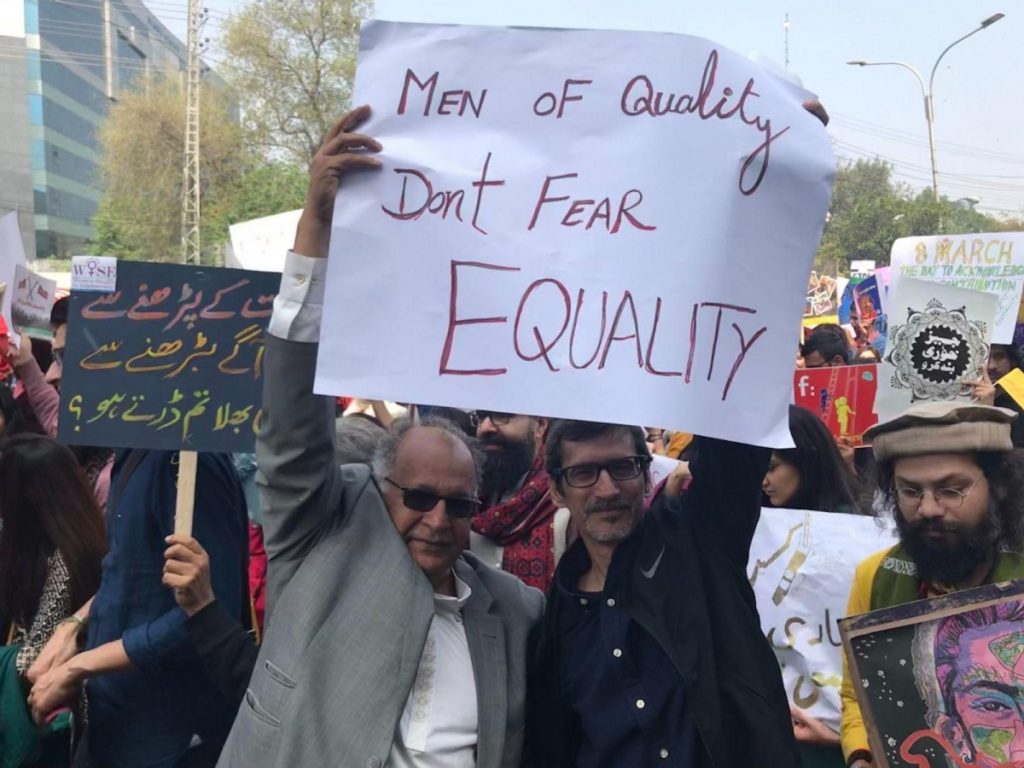

The event got bigger in subsequent years. Women emerged in throngs to march in multiple cities – Karachi, Hyderabad, Lahore, Multan, Islamabad, even Hunza valley. Men, too, began to join the event with their families and the numbers have continued rising, despite the increasing threats the event receives from conservative elements.

Men have started participating in the Aurat March as well. Photo: Sapan News Service.

The slogans raised at the March since its inception have created a furore because they “challenge dominant norms and gender roles by calling for autonomy, equality, freedom and justice,” according to Daanika R. Kamal, PhD scholar at the School of Law, Queen Mary University of London.

In addition to the ones detailed above, the participants of the March raise sensitive issues such as child rape and sexual abuse, honour killings, transgender rights and so on, as reflected by the manifestos and charters released by the organisers, which vary slightly in each city the March is held in.

This year, the Aurat March in Karachi is calling for social security, demanding Ujrat, Tahaffuz, Sukoon (Wages, Security, Peace). Lahore is focusing on ‘repair and reform’, calling for justice for rape victims, reproductive health and transgender rights and Multan is calling for ‘reimagining the education system’.

1/n

Aurat March Multan is too overwhelmed to reveal the theme of this year Aurat March claiming the reason to join aurat March 2022. While depicting inclusion, AM came up with “Reimagining the Education System” /

وسیب دی ترقی

عورت دی تعلیم pic.twitter.com/XmZpJwapvX— Aurat March Multan- عورت مارچ ملتان (@AuratMarchMultn) February 27, 2022

The opponents of the March seem totally unaware of these issues and refuse to ever engage in dialogue about them.

There was great opposition to one of the slogans raised at the 2019 March: ‘Mera jism, meri marzi’ (My body, my choice). This call to end gender violence, sexual harassment and bonded labour was dismissed by opponents of the March as a call for ‘sexual libertarianism’. However, women continued to defiantly chant the slogan at subsequent events. Celebrities, such as actor Mahira Khan, even came out in support of the March, taking to Facebook to explain what the slogan meant.

“I feel that the Aurat March has changed the narrative about women’s rights,” says performing artist Sheema Kermani, one of the founding members of the March. “It has shaken the very foundations of patriarchy and brought the dialogue on women’s rights into every home, every family, in offices and on the roads.”

Another allegation that opponents level at the March is that it is unsafe. However, I, personally, have found it one of the safest public spaces in Pakistan. No incidents of jostling and ‘eve-teasing’ have ever been reported from these events.

Aurat March demonstrations are inclusive events attended by women from different backgrounds and sharing divergent thoughts and beliefs. Large numbers of women in burqa and hijab march in harmony with women in shalwar kameez; some with dupattas, some without. There are women in saris and in there are women in jeans. Everyone is welcome. It provides a chance to engage in dialogue and understand different perspectives. That is how civilised societies find solutions to the problems they face.

And yet, not only has the March been met with increasing opposition, threats to the event have only continued to grow, reflecting a deepening societal divide on the topic of moral and social values.

False allegations and social media disinformation campaigns are being used to try and discredit the event, such as photoshopped placards with distorted the messages. Last year’s March saw one of the worst examples of this: A doctored a video of the Karachi March was circulated making it seem as if the participants had committed “blasphemy” – a charge that in Pakistan can lead to the accused being killed by vigilantes. It wasn’t until Geo TV anchor Shahzaib Khanzada investigated the issue and showed how the video was falsified that the controversy died down.

The Aurat March has proved to be a phenomenal success, forcing society to acknowledge the efforts of women and sparking nationwide debates about the rights women are entitled to, but denied.

The women of Pakistan want to develop collective communities of care, building on existing support. Why is it such a bad idea to build supportive communities that hold themselves accountable, have mechanisms to address abuse, support victims of violence, and create awareness around health issues and legal rights?

Why do many in Pakistan see their demands: access to safe public spaces; the right to voice their views; to receive equal wages; to respect all belief systems; to integrate trans individuals as useful members of society; in short, a claim to basic human rights, as a threat to society?

Those who oppose Aurat March must realise that it is important for all of us to work together to break the biases that hold back half our population.

Nadra Huma Quraishi is an educationist and a member of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan.

This article was produced by Sapan News Service.