New Delhi: The World Health Organisation (WHO) has announced changes for the treatment of drug-resistant TB. These are especially focused on knocking off toxic drugs which have long been part of TB treatments. The changes also hope to make the treatment course shorter.

The WHO is thus keen to increase priority for bedaquiline, a drug that has been gaining acceptance over the past few years. The organisation also recommended a new drug, pretomanid, but only for a limited and cautious roll out for now.

Drugs like bedaquiline and pretomanid can be taken orally, can shorten the regimens and can treat drug-resistant TB. They can replace painful injectable drugs that sometimes cause deafness.

India is also keen to hop on to the “all-oral regimen” and is updating its guidelines as of this year, as The Wire reported in September.

So firstly, WHO’s new communication hopes to move multidrug-resistant TB and rifampicin-resistant TB (MDR/RR-TB) patients on to shorter, all-oral regimens with the drug bedaquiline. Secondly, it has introduced the novel treatment regimen of drugs called BPaL, which has the new drug pretomanid.

Also Read: As Focus Moves to TB Prevention, Who Will Treat India’s 2.69 Mn Patients?

The problem of MDR/RR-TB is a unique challenge on its own, within the larger challenge of global TB. About 5 lakh new cases of MDR/RR-TB are said to emerge annually and only one in three are reportedly being treated as of 2018. The success rate for treatment in 2018 was 56% for MDR/RR-TB patients and 39% for XDR-TB patients.

The global health body hopes that the new regimens will show “significant improvements in treatment outcomes and quality of life for patients.” The communication is expected to influence and change various national TB programmes.

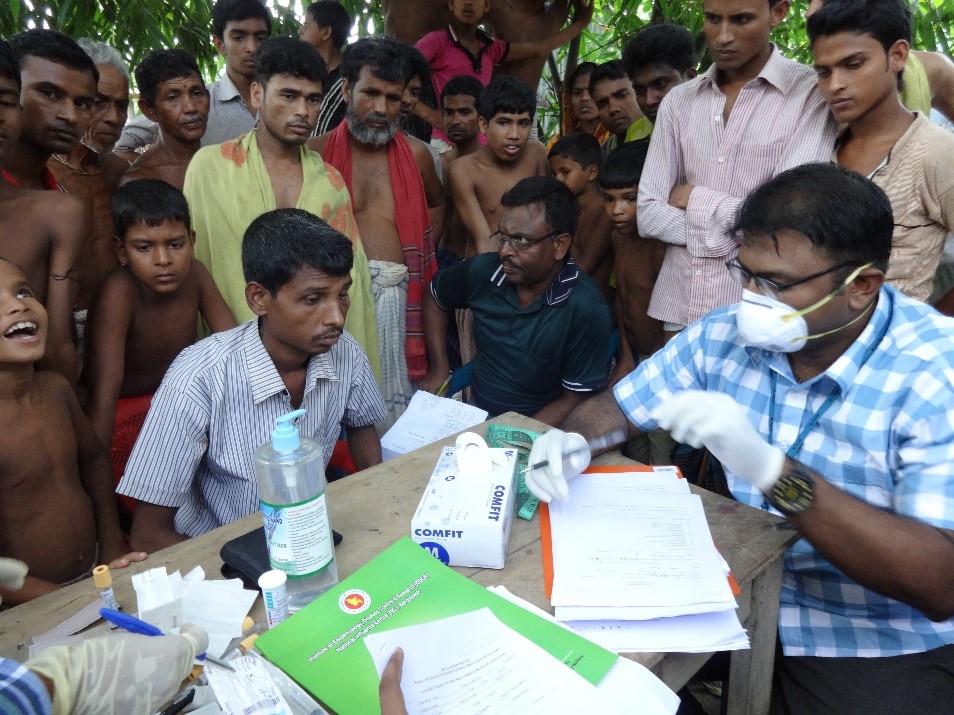

WHO hopes to eliminate injectable drugs. Credit: WikiImages/pixabay

New drug pretomanid is exciting but questions remain

Pretomanid is a new drug developed by the TB Alliance, a non-profit organisation. It is also an oral tablet, which makes it an attractive alternative to painful injectables. It has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration just this August. The TB Alliance has not published the data on its study of this drug.

WHO’s new recommendation for BPaL is important and requires more analysis.

BPaL is a new regimen with bedaquiline, pretomanid and linezolid. Linezolid is an old drug, well known for TB treatment, bedaquiline has become known over the past few years, while pretomanid is new.

Data for BPal so far is from the single-arm, open-label Nix-TB study done by the TB Alliance, which also owns the drug. The study looks at whether BPaL is successful in a six to nine-month regimen for patients with XDR-TB when compared with other regimens. The study has also only looked at patients who have not had exposure to bedaquiline and linezolid so far.

WHO also noted the fact that there were only 108 participants in the study as a limitation. The study also did record some adverse events such as blood disorders, liver toxicity, peripheral and optic neuropathy. WHO says that reproductive toxicities have been seen in animal studies and there has not been enough evaluation of its impact on human fertility. It says that patients should be informed about this before being given the drug.

Also Read: India Looks to Expand TB Programme With New Drug Bedaquiline

Therefore, WHO has recommended that BPal is only given in “operational research conditions” which conform to the organisation’s standards for patient care, support and inclusion, good clinical practice, active drug safety monitoring and management, treatment monitoring, evaluation of outcomes and standardized data collection.

The global body says that BPaL is not for programmatic use worldwide “until additional evidence on efficacy and safety has been generated.”

WHO has weighed the benefits and risks of pretomanid and says that the experience with BPaL is limited but that “the BPaL regimen may offer benefits despite potential harms and may be considered under prevailing ethical standards.”

File photo of the headquarters of the World Health Organization (WHO). Photo: Reuters/Denis Balibouse/Files

Concerns about pretomanid are pending answers

At The Union’s World Conference on Lung Health in Hyderabad recently, global health activists and TB patients demanded that the TB Alliance release more data and answer questions about the safety of the drug. They also demanded the Alliance drop the high price of the drug [pretomanid alone will cost about $364 (Rs 25,670) and when taken in combination will cost $1,040 (Rs 73,342)]

Twenty four TB experts have also recently written to the TB Alliance with questions. They want to know the results of patients on BPaL versus patients taking only bedaquiline and linezolid. They also ask if the Alliance has buried negative data from trials in 2015 about liver toxicity, when three deaths were reported. The data from this study has never been published and the new data for pretomanid has also not been published.

A piece in The Lancet recently said that analysts felt pretomanid “risks lowering the evidentiary standards required for new tuberculosis medicines.” The authors concluded: “We think more research is needed before pretomanid can be celebrated as a promising treatment for people with tuberculosis.”

The new changes were announced this week by WHO after their ‘Guideline Development Group’ deliberated in November 2019, to look at new evidence shared by countries and technical partners and through WHO’s public call for data on TB drugs.

The organisation will convene a global forum in 2020 to help countries, technical partners and civil society understand the important changes in the new regimens and also to restructure national guidelines and TB programme budgets.