Last week, India hosted the ‘Delhi End TB Summit‘, with a host of world leaders including the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. India has the world’s highest population of people living with tuberculosis (TB), including about one million who are estimated to not yet be diagnosed. At the summit, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said, “I am confident that India can be free of TB by 2025.”

The Wire’s Anoo Bhuyan interviewed Lucica Ditiu, the executive director of the ‘Stop TB Partnership’, a global network of organisations working to eliminate TB while consolidating political support for it. The partnership cohosted the summit along with WHO and the Indian government. Ditiu discussed India’s plan to eliminate TB by 2025, which is five years sooner than the global target of 2030. She also discussed issues around access to drugs for drug-resistant TB and civil society’s demands for the Indian government to force cheaper production of these drugs.

As someone who has been tracking TB for a long time, where do you see India- What are we doing right and wrong on TB at this moment?

LD: I see India doing very good things, now. They have not covered the entire country and the scale is obviously not there- we’re speaking of a country with the largest scale of TB patients that one can think of. But in terms of policy and the National Strategic Plan, most of the things that should be done, are there. I think finances for the plan are increasing. So in terms of what should be done, the mindset, the political and financial commitment, things are not bad. Not perfect. But it’s a very good beginning.

I’ll tell you what needs to be worked on. There are two things in my opinion. Firstly, India plans to end TB by 2025. Ending it doesn’t mean it will go to 0 people with TB. There is a definition at the global level. Currently, India’s level is more than 200 per 1,00,000 people. The definition of zero TB, is 10 per 100,000. It’s a long way to go, as you know. But the important thing is, now we’re in 2018, so, to eliminate TB by 2025, we need to make an intensive effort. The country and its leaders should know that the same level of enthusiasm and energy that we see now needs to persist for the next 7 years. This is the biggest challenge because it’s very difficult to maintain the engagement, political commitment, effort and funding. For me this is a huge threat because if something else becomes more important than TB, India will not achieve its goal of eliminating TB.

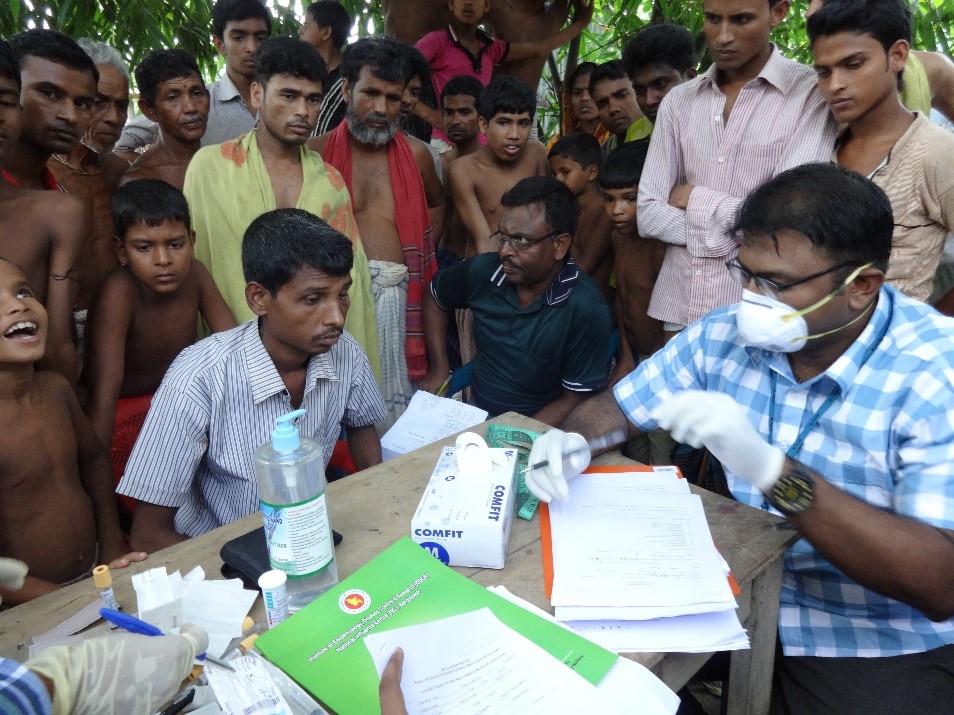

My second worry is about the implementation arrangements. This is related to the fact that you can have the best decision and the funding, but there are many steps from the capital in Delhi to the smallest village in Delhi. The real distance is also in the mind. At this huge scale, the systems should be constructed and put to work so that this becomes possible.

Lucica Ditiu, executive director of the Stop TB Partnership. Credit: StopTB Partnership

This is what I want to say to the government, that it will be extremely important to have the mind to think this for India. At this scale, you’re going into a battle with TB, and you need to have an army. The worst thing can be that all of these things are available, but because of bureaucracy, legislation and complications, things don’t get implemented. It’s not just India, this has happened in many other places as well.

India’s goal is to eliminate TB by 2025, which is 5 years sooner than the rest of the world. But we also have the largest TB population in the world. After these days of deliberations with the Indian government, what is in place and what is not in place?

LD: This is very much linked to the first question. What is in place as I said, is an incredible political commitment. I have to tell you that Prime Minister Modi is the only head of state currently of such a large nation that came out there and set up a very bold target, asked for a strategic plan and personally monitors what’s going on. Funding is increasing, I understand. I understand the government has plans for nutritional support of TB patients very soon.

What I think needs to be worked on, as I said and everyone is aware of, implementation arrangements need to be done. How do you expand? You need to have a very large management team beyond the technical capacity, at the central level and state levels. That’s why the ministries of state are very important and they came as well for the summit.

But specifically, what is not in place? What can you prescribe to India, on the biggest, most gaping holes?

LD: The plan is there. I don’t think there are things that are hugely missing. If we want to make the impact of ending TB by 2025 which is proposed in the national strategic plan, then good. The plan just needs to be implemented.

We also realised recently that India has been under-reporting TB. That’s because of the complicated architecture of the health systems. There are a lot of cases that come to the private sector but they haven’t been tabulated in Indian records. What do you make of the scale of TB in India and what needs to be done to get a more accurate picture of the scale?

LD: This is very correct. It is estimated that maybe a million people with TB are consulting the private sector every year and little is known about what is going on with them- so, regulating the private sector is an important part of ending TB and is a part of the national strategic plan. The scale is large here, in terms of the private sector. There are many types of private hospitals, like your big private networks. But also there are very small cabinet type providers all over, which are the first entry points for many patients. So, there is an entire component in there to bring them on board in different ways.

For a long time, WHO promoted public-private mixes. But at that time, in their perspective, they were sort of obliging the private sector to play ball. That does not work with the private sector. There needs to be thoughts about models that work in other places- to give a carrot to the private sector for them to report TB, but also to continue to provide care to those with TB. This is part of the national strategic plan. It’s not a new thing coming from me. It is there. As I said, implementing it and going with it beyond big cities, to every single state, that is the challenge.

What is your stand on the TB drugs Bedaquiline and Delamanid for drug resistant TB? I have seen your tweets on this. Where do you stand and what do you think India should do on this?

LD: Bedaquiline and Delamanid are two good drugs, but not the drugs that will cure TB on their own. They are drugs to be added to another regimen. According to WHO, its not for everybody. It’s for a subset of a subset of patients. There are about 40000 people who might need it in India but not more than that. But for more than 2 million people with TB in India, this is very small number. And WHO and international recommendations are saying that it should be given under certain conditions. So it’s a very good drug. They are two very good drugs to make life of people with certain types of TB much easier.

India has access to Bedaquiline as part of a donation between USAID and Janssen currently. I understand, that the Government of India entered into a discussion to see what they can do from 2020 onwards. By then we may get new regimens that include these drugs but will be shorter. So hopefully, many things for India and the world will change by then.

But what I want to say, as I told our colleagues in civil society, is that India should accelerate diagnosing people with drug resistant TB this year. Because Bedaquiline and Delamanid are for these people. In order to give the drug, you need to have people diagnosed. This part of the strategic plan needs to be implemented. To diagnose people and put them on treatment.

These two drugs have some side effects. Any drug will have side effects. However, the side effects of these drugs are linked to cardiovascular systems, so you need to have proper systems to monitor these drugs. You cannot give it to me and say “Lucica, go and be somewhere in a village and I’ll see you in three months,” because in the meantime if I get side effects, I need to see a doctor and have a conversation about it. To really scale up Bedaquiline and Delamanid, you need to ensure you have the ability to diagnose these people, and the right system in place to monitor them.

So I think this is a good opportunity to build all this while this donation programme still exists. And then go to 2020 on a bigger scale. I think this is the plan of the government.

On the issue of Bedaquiline and Delamanid, phase 3 trial data has not come in from anywhere in the world. Phase 3 trials have not even been conducted in India. In light of this, what is keeping you confident about Bedaquiline and Delamanid, and their safety and efficacy?

LD: South Africa is using Bedaquiline and Delamanid a lot in their clinics, but under the conditions I told you about, because WHO has issued clear standards. Under those WHO standards, evidence from the field, like South Africa, is very encouraging for people who have a very bad prognosis. People with several months of multi-drug resistant treatment, who were not doing well, did very very well after treatment with Bedaquiline. But indeed, we need more evidence to go at the huge scale and that’s what WHO is preparing itself very soon for, looking into whatever data is coming in.

Even in the US when [Bedaquiline] was given an accelerated approval, Janssen was told to come back with the data. That was in 2012. Does it worry you that the data hasn’t come out so far? Why don’t we have this data yet?

LD: My focus now is very much on the scale of the programme. I don’t know the real answer to this.

The Indian government does waive off phase 3 trials, but that is when phase 3 has been done somewhere else.

LD: We spend a lot of energy on Bedaquiline and Delamanid. I don’t think that pays back. I think that’s a very good discussion but there are many questions to be answered on this and they have to go in parallel. To properly treat multi-drug resistant TB, you need a cocktail of drugs. These two drugs, the research phase in South Africa, show good results, for small groups of people. You know what I mean? But speaking of treating two million people in India, and finding one million in the private sector, is a huge undertaking. And I’ll be very happy for India to find more people in need of Bedaquiline and Delamanid. They can have as much as they want next year. That’s what I’m focused on. I don’t think I’m the right person to comment on the pure research of Janssen and what they’re doing on the trials.

Confidence usually it comes from data, but the data has not yet come in. A letter has been signed by 60 individuals and organisations worldwide asking India to make this drug accessible. I’m trying to understand what this is based on. Where do you stand on this letter asking India to issue a compulsory license on the drugs? This would allow generic companies to make the drug at a cheaper price. Is this what India needs to do?

LD: To be honest, I think the letter was very limited. I was very disappointed. Civil society in India should ask, where is the missing million? They should ask the government to work with the private sector and find those. Making all that effort in a letter only on Bedaquiline and Delamanid, I don’t think will move the needle. If I was in civil society, I would want to ask for every single person in India to have quality care and treatment. That’s what they should ask. By going piecemeal and speaking only about Bedaquiline and Delamanid now in 2018, when we don’t know how it works, when we don’t know how many people need it, for me was a missed opportunity. It was a bold letter. But new tools, new drugs, new regimens, more money for research, should have been part of it. That should have been something in it.

If the focus is trained on Bedaquiline and Delamanid, are we missing something else?

LD: They just need to implement the national strategic plan. If India can do that, it will be kilometres ahead. The attention should be on finding everyone with TB, diagnosing them and putting them on treatment. And I think if the civil society wants to move, and interact with the government, then they should ask to be part of not only developing the implementation plan, but also monitoring it. Civil society should be watching and asking if the money for nutrition reaching people, if the diagnostic technology accessible, etc. That’s what I think civil society should do- organise themselves to be a part of the solution and also a part of the monitoring.

India is being criticised for being slow on the access to these drugs. Given what we know – that the drugs are showing good results, but we don’t have all the data. That there are other issues which India also needs to simultaneously attend to. That infrastructure for monitoring needs to be in place, but India is challenged on that… Given all this, is it wise for India to continue on a conservative conditional access programme as it is currently doing? Or open the flood gates?

LD: I don’t know. As I keep saying, I’m looking at this from a different perspective. More data is needed for these two drugs, to understand how they work, how they interact with each other, with HIV drugs, with children. We need to know more. South Africa is providing more evidence. A time might come – in fact, it already has come – when we will put these two drugs together and see, what if we put other innovative ideas and obtain a regimen that can be just four or five months in length…

So we cannot afford to throw these drugs into a population, create resistance to them and lose them. In terms of whether India will scale or not, I don’t know. But the need for more data is very great.