We are headed towards a future that is hard to contemplate. At present, global emissions are reaching record levels, the past four years have been the four hottest on record, coral reefs are dying, sea levels are rising and winter temperatures in the Arctic have risen by 3°C since 1990. Climate change is the defining issue of our time and now is the moment to do something about it. But what?

Society often looks to culture to try and make some sense of the world’s problems. Climate change challenges us to look ahead, past our own lives, to consider how the future might look for generations to come – and our part in this. This responsibility requires imagination.

So, it is no surprise that a literary phenomenon has grown over the past decade or two which seeks to help us imagine the impacts of climate change in clear language. This literary trend – generally known by the name “cli-fi” – has now been established as a distinctive form of science fiction, with a host of works produced from authors such as Margaret Atwood and Paolo Bacigalupi to a series of Amazon shorts.

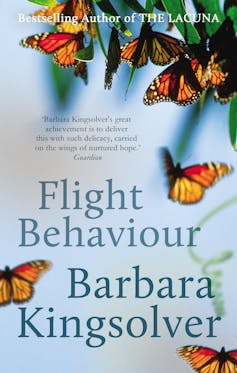

Often these stories deal with climate science and seek to engage the reader in a way that the statistics of scientists cannot. Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behaviour (2012), for example, creates emotional resonance with the reader through a novel about the effects of global warming on the monarch butterflies, set amid familiar family tensions. Lauren Groff’s short story collection Florida (2018) also brings climate change together with the personal set amid storms, snakes and sinkholes.

The end to come

Cli-fi is probably better known for those novels that are set in the future, depicting a world where advanced climate change has wreaked irreversible damage upon our planet. They conjure up terrible futures: drowned cities, uncontainable diseases, burning worlds – all scenarios scientists have long tried to warn us about.

These imagined worlds tend to be dystopian, serving as a warning to readers: look at what might happen if we don’t act now.

Atwood’s dystopian trilogy of MaddAddam books, for example, imagines post-apocalyptic futurist scenarios where a toxic combination of narcissism and technology have led to our great undoing. In Oryx and Crake (2003), the protagonist is left contemplating a devastated world in which he struggles to survive as potentially the last human left on earth. Set in a world ravaged by sea level rise and tornadoes, Atwood revisits the character’s previous life to examine the greedy capitalist world fuelled by genetic modification that led to this apocalyptic moment.

Also read: At UN Climate Summit, Green Funds, Collective Commitment in Focus

Other dystopian cli-fi works include Paolo Bacigalupi’s The Water Knife (2015), and the film The Day After Tomorrow (2004), both of which feature sudden global weather changes which plunge the planet into chaos.

Dystopian fiction certainly serves a purpose as a bleak reminder not to act lightly in the face of environmental disaster, often highlighting how climate change could in fact compound disparities across race and class further. Take Rita Indiana’s Tentacle (2015), a story of environmental disaster with a focus on gender and race relations – “illegal” Haitian refugees are bulldozed on the spot. A. Sayeeda Clarke’s short film White (2011), meanwhile, tells the story of one black man’s desperate search for money in a world where global warming has turned race into a commodity and circumstances lead him to donate his melanin.

The future reimagined

It is this primacy of the imagination that makes fictional dealings with climate change so valuable. Cli-fi author Nathaniel Rich, who wrote Odds Against Tomorrow (2013) – a novel in which a gifted mathematician is hired to predict worst-case environmental scenarios – has said:

I think we need a new type of novel to address a new type of reality, which is that we’re headed toward something terrifying and large and transformative. And it’s the novelist’s job to try to understand, what is that doing to us?

As the UN 2019 Climate Action Summit attempts to bring the 2015 Paris Agreement up to speed, we need fiction that not only offers us new ways to look forward, but which also renders the inequalities of climate change explicit. It is also key that culturally we at least try to imagine a fairer world for all, rather than only visions of doom.

When now is the time that we need to act, the rarer utopian form of cli-fi is perhaps more useful. These works imagine future worlds where humanity has responded to climate change in a more timely and resourceful manner. They conjure up futures where human and non-human lives have been adapted, where ways of living have been reimagined in the face of environmental disaster. Scientists, and policy makers – and indeed the public – can look to these works as a source of hope and inspiration.

Futures are built out of our collective imaginaries. Photo: RomanYa/Shutterstock.com

Utopian novels implore us to use our human ingenuity to adapt to troubled times. Kim Stanley Robinson is a very good example of this type of thinking. His works were inspired by Ursula Le Guin, in particular her novel The Dispossessed (1974), which led the way for the utopian novel form. It depicts a planet with a vision of universal access to food, shelter and community as well as gender and racial equality, despite being set on a parched desert moon.

Robinson’s utopian Science in the Capital trilogy centres on transformative politics and imagines a shift in the behaviour of human society as a solution to the climate crisis. His later novel New York 2140 (2017), set in a partly submerged New York which has successfully adapted to climate change, imagines solutions to more recent climate change concerns. This is a future that is mapped out in painstaking detail, from reimagined subways to mortgages for submarines, and we are encouraged to see how new communities could rise against capitalism.

This is inspirational – and useful – but it is also is crucial that utopian cli-fi novels make it clear that for every utopian vision an alternative dystopia could be just around the corner. (It’s worth remembering that in Le Guin’s foundational utopian novel The Dispossessed, the moon’s society have escaped from a dystopian planet.) This is a key flaw in the case of Robinson’s vision, which fails to feature the wars, famines and disasters outside of his new “Super Venice”: the main focus of the book is on the advances of western technology and economics.

Forward-thinking cli-fi, then, needs to imagine sustainable futures while recognising the disparities of climate change and honouring the struggles of the most vulnerable human and non-humans. Imagining positive futures is key – but a race where no one is left behind should be at the centre of the story we aspire to.

Bernadette McBride, PhD Candidate in Creative Writing, University of Liverpool

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.