In the NITI Aayog’s recently released Health Index 2018, Chhattisgarh ranks fifth – i.e. shows the fifth highest gains in improvement of its health outcomes from the base year (2014-15) to reference year (2015-16). NITI Aayog assessed states’ performance across indicators such as neonatal mortality rate, under-five mortality rate, full immunisation coverage, institutional deliveries, and people living with HIV on antiretroviral therapy. However, there is still a long way to go.

Communicable diseases continue to pose a threat to the health profile of Chhattisgarh. A report published by the Indian Council of Medical Research and the PHFI notes that in Chhattisgarh, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and other lower respiratory infections, diarrhoea and malaria together have led to 39% of deaths in 2016 among children between 0-14 years of age. Recent figures from the National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme show that in 2017, Chhattisgarh alone accounted for 42% of all malaria-related deaths in India.

Maternal and childhood mortality

Chhattisgarh has also been in the news for its success in reducing Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) from 221 per 1,00,000 live births in 2011-13 to 173 per 1,00,000 live births in 2014-16, according to the new data released by the Registrar General of India. While Chhattisgarh’s reduction in maternal mortality is congratulatory, absolute levels of both maternal and childhood mortality figures in the state remain quite high. The state figure for MMR is an astounding 33% higher than the national figure for the same. The NFHS-4 estimates that the infant mortality rate in Chhattisgarh as 54 per 1,000 live births, and the under-five mortality rate as 64 as 1,000 live births, in 2015-16. While both have witnessed a decline of 24% and 29% respectively from 2005-06, they too remain quite high in comparison with the national figures.

A disaggregation by background characteristics reveals that infants and under-five children who are male, residing in rural areas and belonging to Scheduled Tribe/Other Backward Class category are worse off than their female, urban, non-Scheduled Tribe/non-Other Backward Class counterparts. Table 1 presents the infant and under-five mortality rates, disaggregated by residence, caste/ tribe and child’s sex, as well as schooling and mothers’ age at birth (NFHS 4). That Scheduled Tribes are worse off in terms of childhood mortality is a pressing concern, especially since they constitute a considerable proportion of the state’s population. This further calls into focus the need for the state to devise strategies which can reconcile traditional medicine with modern healthcare practices.

Table 1: Infant and under-five mortality rate, by background characteristics, 2015-16.

| Background characteristics | Infant Mortality Rate | Under-five Mortality Rate |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 44.4 | 51.0 |

| Rural | 56.4 | 67.7 |

| Caste/tribe | ||

| Scheduled Caste | 41.7 | 56.4 |

| Scheduled Tribe | 65.8 | 80.0 |

| Other Backward Classes | 53.6 | 60.5 |

| Other | 23.5 | 27.6 |

| Child’s sex | ||

| Male | 57.1 | 68.6 |

| Female | 50.7 | 59.7 |

| Schooling | ||

| No schooling | 73.6 | 86.0 |

| 53.163.4 | ||

| 10 or more years complete | 32.9 | 39.8 |

| Mother’s age at birth | ||

| <20 | 66.8 | 79.6 |

| 20-29 | 51.0 | 61.9 |

| 30-39 | 56.5 | 61.8 |

A peek into the situation of infant and young child feeding practices in Chhattisgarh can, to some extent, explain childhood mortality in the state. While the World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding for every child under 6 months, only 77% of children under 6 months in Chhattisgarh are exclusively breastfed. Many infants are still deprived of the highly nutritious first milk (colostrum) and the antibodies it contains. After completion of 6 months, infants require complementary foods to fulfil their nutritional needs which breastmilk alone cannot deliver. It is striking that only 54% of children between 6-8 months in Chhattisgarh receive breastmilk and complementary foods (NFHS-4), leaving a lot of scope for improvements in child feeding practices in the state.

Health facilities in Chhattisgarh

Has the state’s health infrastructure exacerbated or contained these outcomes? Using data from the Rural Health Statistics, a look at the rural health infrastructure in Chhattisgarh points out that in the last decade, a total of 459 new sub-centres, 72 new Primary Health Centres (PHC), and 33 new Community Health Centres (CHC) have been established between March 2008 to March 2018. Of the 5,200 sub-centres in the state as on March 2018, 27% do not have regular water supply and 15% do not have electricity. While the majority of PHCs out of the total 793 PHCs enjoy regular water supply and electricity and are well connected with an all-weather motorable road, only 35% function on 24×7 basis. Further, only 5 out 169 CHCs in the state employ all four specialists (surgeon, physician, obstetrician/ gynaecologist and paediatrician) as per government norms. Sadly, none of the sub-centres, PHCs and CHCs function as per the Indian Public Health Standards (IPHS), which were published in 2007 as the reference point for public health care infrastructure planning and upgradation in the States and Union Territories.

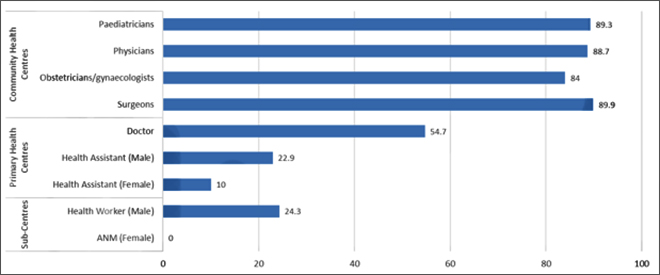

Health workforce in these facilities, particularly in PHCs and CHCs, presents a grim picture as well. There is a dearth of medical doctors in PHCs. As against 793 medical doctors sanctioned for PHCs, only 359 are in position. In CHCs, the non-availability of general physicians is an acute problem, with only 13 physicians in position as against the 163 sanctioned. The only respite is the availability of Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANM) in sub-centres and PHCs, which far exceeds their requirement. Figure 1 depicts the total number of staff in position as against those sanctioned for each of the facilities (RHS 2018).

Figure 1: Vacancy (%) out of total sanctioned (as on 31 March 2018)

The successful relaunch of sub-centres and PHCs as Health and Wellness Centres under the Ayushman Bharat makes it imperative that infrastructural shortcomings especially in terms of workforce be dealt with swiftly, which coincides well with the establishment of India’s first Health and Wellness Centre in Bijapur district of Chhattisgarh. A possible solution could be to strengthen the cadre of rural medical assistants (RMAs) — a special cadre of mid-level healthcare providers — and develop their capacity as primary healthcare providers. Interestingly, a study published in 2010 by the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI) and the National Health Systems Resource Centre has noted that RMAs with a three-year diploma are equally competent as a doctor with an MBBS in providing primary healthcare, even though the Indian Medical Association staunchly opposes the introduction of a three-and-a-half year course for mid-level health practitioners in and for rural India citing quality concerns.

Nutritional status of children

Nutrition and health go hand-in-hand. Any discussion about health is incomplete with a conversation around nutrition. In Chhattisgarh, the status of two key nutritional indicators for children — stunting (low height for weight) and underweight (low weight for age) — shows a hopeful trend. NFHS-3 and NFHS-4 show that the percentage of children under 5 years who are stunted has gone down from 53% in 2005-06 to 38% in 2015-16. While the percentage of underweight under-five children has also reduced from 47% in 2005-06 to 38% in 2015-16, it remains higher than the national figure. The figures for wasting (low weight for height), however, have worsened over time, with the percentage of wasted under-five children actually increasing from 19% in 2005-06 to 23% in 2015-16, which is also higher than the national figure.

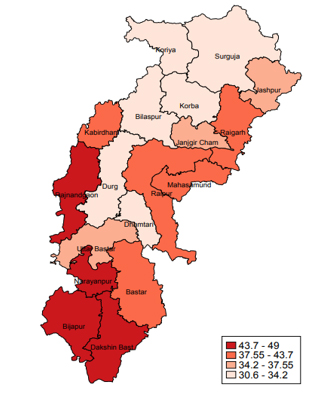

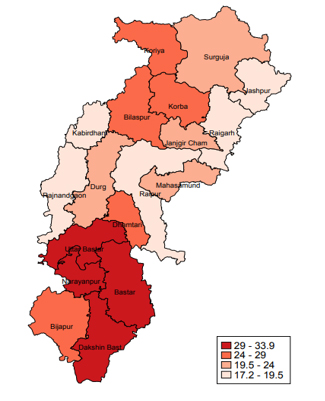

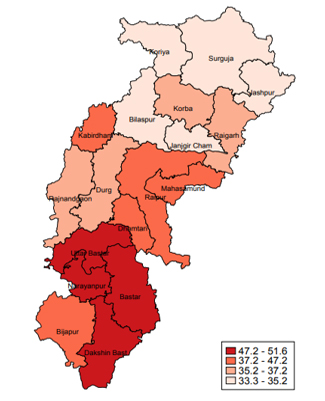

At the district level, 9 out of 18 census districts report a higher incidence of stunted and wasted children than the state average. Bastar records the highest percentage of under-five children who are wasted- 33%. Similarly, Narayanpur at 49% and Dakshin Bastar Dantewada at 52% record the highest percentage of under-five children who are stunted and underweight, respectively. Figures 2, 3 and 4 depict the district level figures for the three nutritional indicators in 2015-16 (NFHS 4).

| Figure 2: Stunting (%)

|

Figure 3: Wasting (%)

|

| Figure 4: Underweight (%)

|

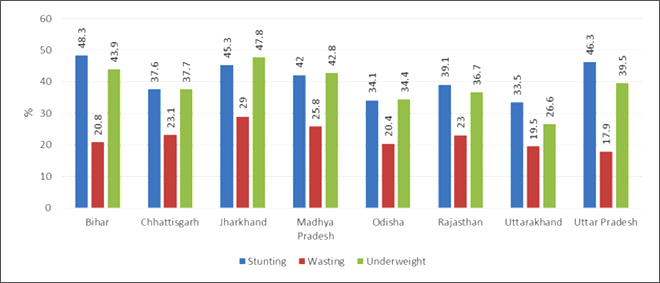

Chhattisgarh is also one of the eight Empowered Action Group (EAG) states, which have the highest infant mortality rates in the country. In comparison to other EAG states, nutritional indicators for under-five children indicate that Chhattisgarh fares slightly better than Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh with regards to stunting. The proportion of underweight children in Chhattisgarh is also lesser in comparison to the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh. However, it has the third highest proportion of wasted children among all the EAG states. Figure 5 compares the EAG states with regards to their child undernutrition figures in 2015-16 (NFHS 4).

Figure 5: Nutritional indicators in EAG states, 2015-16

One of the major efforts to tackle the problem of undernutrition among children in the country was rolled out in the form of the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS) in 1975. Under the scheme, nutrition and health services are provided to children under six years, and pregnant and lactating women. In Chhattisgarh, in 2015-16, pregnant and lactating women have a higher uptake of ICDS services, as compared to children under six. The coverage of ICDS services has evaded 23% of the under-six population. The provision of supplementary food, health check-ups, and immunisations has further covered only 72%, 68% and 63% of the under-six population respectively (NFHS-4).

The way forward

In the run up to the upcoming state elections, chief minister Raman Singh has reiterated his commitment to the basics of development — healthcare, education, roads and jobs. With the state serving as ground zero for the government’s ambitious health insurance scheme, Ayushman Bharat — Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY) — which as of 22 October 2018 has already touched lives of 20,000 beneficiaries in Chhattisgarh — it is not very difficult to see that commitment bearing fruit. However, while the Health Index 2018 accords a favourable position to Chhattisgarh in terms of annual incremental performance, the state ranks 12th in terms of comparative health status as of the reference year 2015-16. Southern districts are particularly worse off in terms of nutritional indicators for children. The time is thus right for the Chhattisgarh government to evaluate bottlenecks in health and healthcare delivery, adopt a targeted approach and prove its potential as a frontrunner in human development.

This article was originally published in ORF Online. Read the original article.