As would-be dictators of variable girth and invariable cruelty attempt to seize the world, we have grown accustomed to drawing easy, maybe lazy, parallels with that seemingly eternal counter-point, Nazi Germany.

But what historical precedent would a dissenting German have looked for during the monstrous growth of the Third Reich? I had never thought of it, until I came across a dissenting German making the attempt.

Friedrich Reck (sometimes Reck-Malleczewen) kept a secret diary from mid-1936 until almost the end of the second world war, “an illegal watcher among the barbarians” he calls himself, observing with increasing horror and disgust the German people’s capitulation – no, devotion – to their mad Führer. During these years, Reck also produced a more public work, a history of Münster, a sixteenth-century city-state established by a radical sect called the Anabaptists. It wasn’t a specialised interest in this obscure bit of history which led Reck to it. “I am shaken” he wrote in his diary – by how closely Münster resembled the Third Reich.

“As in our case,” he continued, “a misbegotten failure… became the great prophet, and the opposition simply disintegrated”. As in Germany, Münster’s alternative for allegiance was death; as in Germany, endless distraction kept the people “from a moment’s pause to reflect”. In every detail, it seems, Münster anticipated the Third Reich: that its “propaganda chief… limped like Goebbels is a joke which history spent four hundred years preparing”.

Reck did not draw such explicit parallels in the history he published – he wrote it camouflaged in footnotes, and even so, it was eventually banned – but he minced no words in his diary. Diary of a Man in Despair speaks as clearly, as cathartically, to anyone who fears the transformation of her world under authoritarian leadership as Münster spoke to its author.

Friedrich Reck. Photo: Twitter

Take for example, the ungrudging, limitless obedience that authoritarians inspire in their flock, even when – especially when – their orders are so very thoughtless, or cruel, or just plain flops. In the final months of the second world war, it was clear that Adolf Hitler had led his country into defeat; German towns were rubble, German currency was waste-paper. Even then, writes Reck, he heard a woman extoll the greatness of her Führer, for “in his goodness, he has prepared a gentle and easy death by gas for the German people in case the war ends badly.”

§

I discovered Reck via Eichmann in Jerusalem, Hannah Arendt’s account of the trial of a Nazi captured and tried by Israel. Arendt recounts his anecdote along with another, similar story of a woman speaking fondly of Hitler’s gracious death-wish for his people. Then, she takes a scalpel and cuts to the selfish, spiteful heart of such devotion: “The story, one feels, like most true stories, is incomplete. There should have been one more voice… which, sighing heavily, replied: And now all that good, expensive gas has been wasted on the Jews!”

It was in this account that Arendt coined her famous phrase, “the banality of evil”. Arendt meant no simple-minded, ‘innocent’ banality, but rather to what Reck calls a “gigantic psychosis… the product of your radio manipulation-stupefied mass-man, and the conversion of human societies into heaps of termites!”

To live among such “thoroughly coarsened people” filled the diarist with rage. He writes with grim satisfaction of how a “revolutionary executive” emerged in the final months of Hitler’s rule, sending warnings of retribution to men and women who had been most enthusiastic in their commitment to Hitler’s cause. One amongst them, a doctor, had stopped treating Jews. Now, his wife told Reck, he had received a warning from the resistance and “had trouble with his nerves, complained constantly about the purposelessness of life and the unreality of the Party pronouncements, and was even toying with ideas of suicide.”

Reck-Malleczewen’s craving for vengeance upon those who enabled Hitler’s rule may have been rare in Germany, but it was not unique. His diary describes, for example, how workers in an electric plant planned to brand Nazi foreheads with swastikas when the Third Reich fell. “A fine idea,” he writes, with the glee one reserves for angry daydreams of justice long-awaited, “which needs only the addition of a single detail to be quite perfect: how would it be if they were forced to wear brown shirts for the rest of their lives?”

Also read: ‘Promise me You’ll Shoot Yourself’: Nazi Germany’s Suicide Wave

It wasn’t these supporters alone, however, these “mass men” as he calls them, these “canaille” – literally, a pack of dogs – that Reck showered with his rage and contempt. It was also their seeming anti-thesis: big business. “The instrument of power is terror,” he wrote, “and the industrialists hold tight to it. They control every means of influencing public opinion, and have thereby stupefied the great unproductive mass—salaried people…to the point of idiocy.”

And it was business, Reck argued with aphoristic aplomb, that underpinned the other great scourge of his time: “it has long been a theory of mine that the basic substance of nationalism is of a commercial nature”. Again, he makes the point in brilliant bit of polemic that cannot but resonate with anyone watching countries torn to shreds by divisive politics, all in the name of making them great: “in 1500 there was a German nation, but no nationalism, whereas today, when our eyes are supposed to light up at every trouser button ‘Made in Germany’, we have the reverse: nationalism, and no nation”.

But his greatest anger is reserved for Hitler himself, often expressed with such biting wit, you will laugh out loud. Once, for example, shortly before he was elected and appointed Chancellor, Hitler came to eat, alone, at a restaurant where Reck was meeting a friend. “There he sat,” writes the diarist, “a raw-vegetable Genghis Khan, a teetotalling Alexander, a womanless Napoleon, an effigy of Bismarck who would certainly have had to go to bed for four weeks if he had ever tried to eat just one of Bismarck’s breakfasts…”

Often enough, Reck’s invective against Hitler carries more than a whiff of contempt for his class. “With his oily hair falling into his face as he ranted, [Hitler] had the look of a man trying to seduce the cook,” he writes. Reck, with his country manor, his literary career, his claims to aristocracy, disdained Hitler’s petit-bourgeois origins; but what he loathed was his evil. It was Hitler’s evil that drove the diarist to despair for his country, that provoked some of the most blistering passages in his book: “I hate you waking and sleeping; I hate you for undoing men’s souls, and for spoiling their lives; I hate you as the sworn enemy of the laughter of men…”

§

‘Love’ is often claimed as a force against the divisive, hate-filled politics of authoritarian states and their devotees. Love is powerful, yes; the call for togetherness has the soaring quality, the idealism necessary to sustain any movement. And yet, reading Reck’s white-hot denunciations of the regime that destroyed all that was good in his world, I began to wonder – why must hate be surrendered to the right?

‘Hate speech’ for example, the intellectual preserve of bigots and trolls, what is that except shallow taunts by schoolyard bullies? How can it compare with hate that punches upwards; hate that is born of despair, recognises its own ugliness, yet turns its own soul into a battering ram against the high walls of power?

Also read: Operation Bagration: A June 22 Hitler Had Not Bargained for

“You, up there: I hate you waking and sleeping. I will hate and curse you in the hour of my death. I will hate and curse you from my grave, and it will be your children and your children’s children who will have to bear my curse. I have no other weapon against you but this curse, I know that it withers the heart of him who utters it, I do not know if I will survive your downfall.

But this I know, that a man must hate this Germany with all his heart if he really loves it. I would ten times rather die than see you triumph.”

Love is essential for building – trust and communities and better futures – but when a monstrous power grows before your eyes, do you seek to envelop it with love, or to destroy it with hate? Do you write of hope and try to soar, or do you let your angry tears burn the page?

§

Reck did not confine his dissent to his diary alone. He continued to use the old greeting ‘Grüss Gott!’ – God be praised – while others called out ‘Heil Hitler!’ He walked out of a movie hall showing a propagandist film; his exit evoked “nasty remarks” from the audience. In a café, he joined a table at which the conversation was about fitting punishments for Nazis: “For the Herr Propaganda Minister, an appearance, naked, in the monkey cage at the Hellabrunn Zoo…”

Such minor acts of resistance were fatal. We learn of Hitler’s rise and fall through the horrors of the Holocaust, but Reck’s journal makes clear how any German – no matter how blue-eyed – lived in danger of denunciation, prison, execution. Joking about the Führer was outlawed; you might be guillotined for “undermining the morale of the German army”. Reck witnessed the trial of an elderly doctor sentenced to eight years in jail for possessing foreign currency (“he missed the guillotine by a hair”).

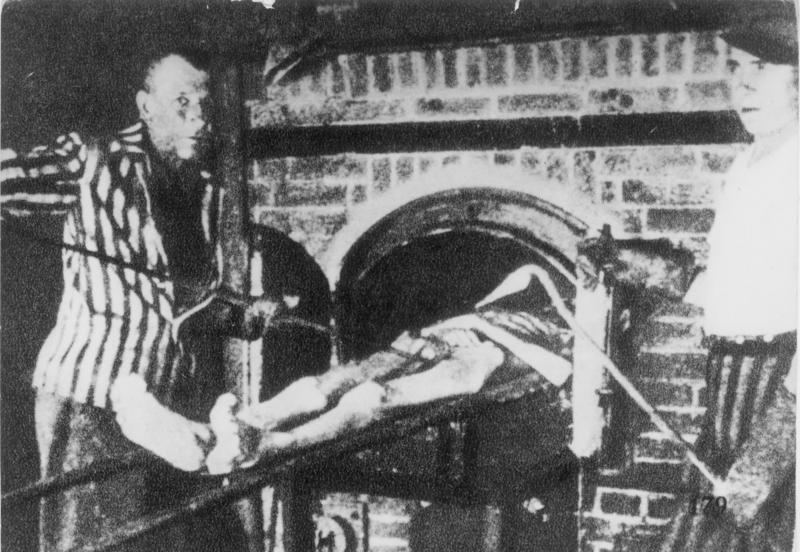

Our diarist was denounced, eventually, too. Possibly, his mistake was to write a letter to his publisher complaining about the falling value of German currency; his royalties were worthless. He was imprisoned, first locally, then at Dachau. In February 1945, just months before the war ended, Reck’s wife was told that her husband had died.

Writers rarely get the royalties they hope for, but sometimes they get the immortality they crave. Reck speaks, still – to his children, and their children’s children – of what it is to stand against a tide, of what courage may be derived from hating with all your heart.

“Only so,” as he wrote, “will we earn the right to search in the darkness for the way of love.”

Parvati Sharma is author of Jahangir: An Intimate Portrait of a Great Mughal (Juggernaut, 2018).