For a best-selling author, Violet Nicolson’s grave gets vanishingly few visitors.

It lies in a hard-to-find corner of one of India’s most unkempt colonial-era cemeteries – a forlorn and abandoned place where obelisks, crosses and funeral statuary peep out from the dense undergrowth.

This is the Island – an overspill burial ground – in the southern Indian city of Chennai (formerly Madras). It’s located a couple of miles from its 17th century mother church, St Mary’s, the oldest Anglican church not only in Chennai but anywhere east of Suez.

There is a poetic aspect to Nicolson’s overgrown burial spot.

Her poems – once hugely popular – are now almost as forgotten as her resting place. She belongs to another era – that last generation of the British in India whose confidence in Empire was unsullied, before war and the rise of nationalism heralded a slow, reluctant retreat.

Also read: Revisiting Hindi Literary Records of Partition

Nicolson, whose formal name was Adela Florence Nicolson, shares the grave with her husband, Malcolm Nicolson, a retired general in the British Indian army.

They died in Madras within weeks of each other in 1904. They were both gifted linguists with a deep affinity for India, and Nicolson offered in her writing a startlingly unorthodox view of Britain’s prize imperial possession.

She wrote of love, longing, suffering and death, and above all of India – of Punjab and the North West Frontier in particular.

Nicolson’s gravestone in Chennai

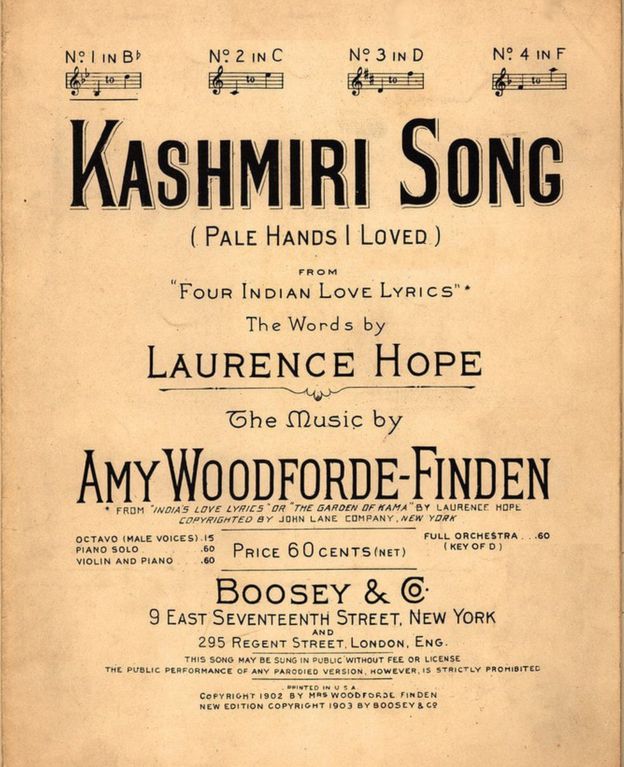

She at first made out that her poems were translations of Sufi-style poetry – and she published under a man’s name, Laurence Hope. But they were all her own work. Her books sold impressively and, while she was never fashionable among the literary elite, the novelist Thomas Hardy was among those who expressed appreciation of her writing.

Some verses of hers, set to music, became massively popular – and kept her name and work alive into the 1930s. One of these began: ‘Pale hands I loved, Beside the Shalimar’. I remember my father singing those lines to no one in particular when I was a young boy. It includes a striking couplet addressed to those ‘pale hands’:

I would rather have felt you round my throat

Crushing out life; than waving me farewell!

The poem is called ‘Kashmiri song’ – “pale” is a reference to the fact that Kashmiris are often described as fair-skinned. There is an ambiguity, perhaps deliberate, about the gender and racial identity of narrator and lover.

Some of her poems are deeply transgressive: addressing not just gender and race, but betrayal, harm and the erotic, in ways which we rarely associate with that apparently strait-laced Edwardian era. Whether this was fantasy, exotic fable, or based in part on experience, we just don’t know.

The story of Nicolson’s death is both tragic and deeply disturbing. Her husband was much older. He needed a prostate operation, but it went wrong and the hospital had run out of oxygen.

A few weeks later, his 39-year-old widow – with a four year-old son in the care of relatives in England – took her own life.

Gossip travels fast, and the word went out that this poet, so knowledgeable about Indian customs and lore, had committed sati – an ancient, and long-outlawed Hindu custom of a wife taking her own life when her husband dies.

Nicolson’s poems gained in popularity after her death, and were published in many editions – from cheap, slim collections to deluxe, embossed volumes with elaborate illustrations. The sombre, reflective tone of her writing seems to have struck a chord in 1920s Britain as the country sought to come to terms with the trauma of World War One.

One of Nicholson’s most popular poems

Her sister, Annie Sophie Cory, was also a writer – using the pen name Victoria Cross, she wrote racy novels. Her most popular, Anna Lombard – published in 1901 – is said to have sold six million copies.

Set in India, it’s about a genteel young English woman who takes her Indian servant as her lover and won’t give him up even when she gets engaged to an eligible English colonial administrator. Her lover dies, but she discovers she is expecting his child. She marries her English fiancé and they move away; when the baby is born, she realises that her husband can never abide this living reminder of her Indian lover. So… she suffocates the child.

It’s fiction, of course. But this sensational storyline does make you pause. The novel violates so much of what is expected of a refined English woman in India at the time.

Also read: Preserving Memories of Partition That Aren’t Our Own

You wonder whose anxieties are being expressed in this tangled plot – and what its emphatic commercial success says about its readership: that they liked to be shocked and appalled or, in some vicarious manner, wanted to share in the thrill, and agony, of a woman who breaks the rules.

The writings of both sisters challenge some of the conventional assumptions about Empire – about the attitudes and experiences of those Britons who made their lives in India. Colonial graveyards such as St Mary’s are often among the most potent epitaphs of an enterprise which by-and-large history does not judge kindly. But delve deeper beneath that dense mat of vegetation, and it’s extraordinary what you can find.

Andrew Whitehead, a former BBC India correspondent, is an honorary professor at the University of Nottingham.

This article was originally published on BBC. Read the original article.