“Hum silai ka kaam karte hai. Ghar pe hum silai mein kama nahi sakte. Isliye hum yahan Dilli export company mein kaam karne aa gaye (I work in textiles and at home there are no avenues to work in that sector. That is why I came to Delhi to work in some of the textile export companies),” said Akash, a 34 year-old textile worker living in a slum settlement near Udyog Vihar, New Delhi. Akash migrated to Delhi from a rural village near Gaya, Bihar at the young age of 17, in search of better livelihood opportunities.

Over the last few decades, due to a widespread lacuna in better employment opportunities across semi-urban and rural areas, the emergence of small-scale manufacturing sites, factory workshops clustered with textile-export companies have made cities like Delhi and its border areas the source of livelihood (and survival) for millions. Unfortunately, during periods of extensive crises, like the one seen during the lockdown of last year and emerging right now, from the wrath of a second pandemic wave, low-income migrant families (those who can’t travel home) like Akash find it difficult to find work or get regular incomes to make ends meet.

‘Atmanirbhar’ migrants of Kapashera

About a mile north-east of the Delhi-Haryana border lies Kapashera, one of the largest migrant-worker residential settlements. An ecosystem of support that amplifies co-existence, Kapashera’s community of migrants – mostly from Bihar and other northern states – have been able to foster a safe, secure and stable environment for low-income working families in a space away from ‘home’ for more than a decade now. The local population of the area is estimated to be over 10,000.

Also read: To Fully Understand the Migrant Worker Crisis, We Need a Larger Perspective

In a three-month-long extensive field study undertaken by our research team at the Centre for New Economics Studies, OP Jindal Global University, before the second wave of the pandemic hit Delhi, we did a randomised survey and documentation of over a hundred low-income migrant families residing in Kapashera.

The study was aimed at understanding the role of principal wage earners in a family, their income, consumption and borrowing patterns during the pandemic, and capturing other day-to-day details of a respondents’ living standards, access to basic utilities (including electronic devices), their children’s education levels etc. Few key observations are discussed here.

Source: Google Earth

Observations from the field

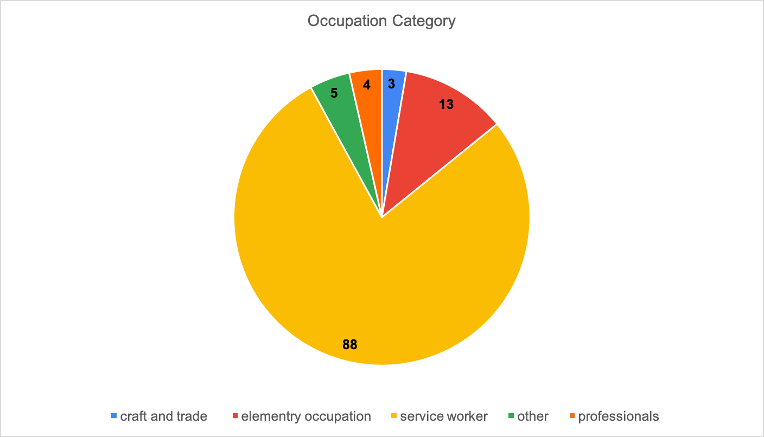

Out of 113 residents of Kapashera interviewed, 87.6% of the respondents are male (being the principal wage earner) and average age of our respondents was 34. The highest education level of each respondent varied from being literate with some high school education (mostly from another state), to those without any formal education, to those who were trained as graduates. Most worked in the self-employed, casual work occupation category within the area of Kapashera itself, while others, with certain skills and tradecraft, found work in textile-export factories near the Gurugram border area and in workshops located in Udyog Vihar.

Source: Authors’ calculations from field data

On income, field data indicates that pre-COVID-19 mean monthly income for an average household in Kapashera was Rs 11,800 per month which fell by a staggering 80% during the government-imposed lockdown for the months of March-May 2020. Even now, before Delhi saw a locked down imposed again in middle of April, their incomes had not risen to their regular (pre-pandemic) levels. Mean monthly income by March 2021 stood at around Rs 10,500 and gradual economic recovery was beginning to revive some manufacturing activity.

The massive loss in income experienced by workers during the lockdown period was primarily explained by the fact that 84% of the respondents had no work, as companies temporarily suspended their operations. None of the respondents we spoke to receive any assistance from their company or contractual employer to help them survive through the lockdown. Agencies of the state – and any hope for support from them – were nowhere to be found.

Sanjay Kumar, a 40-year-old worker in a garment export unit, recalls: “As soon as the lockdown was announced everyone knew that companies would shut down. With no work, everyone in Kapashera was contemplating running back to their hometowns on foot… A lot of families known to us did that. We couldn’t…”

The drastic fall in incomes during the lockdown inflicted significant financial distress for workers and their families. Pre-pandemic, most incomes were spent by respondents on basic expenses (rent, food, medical costs etc.) rendering negligible savings to fall back on.

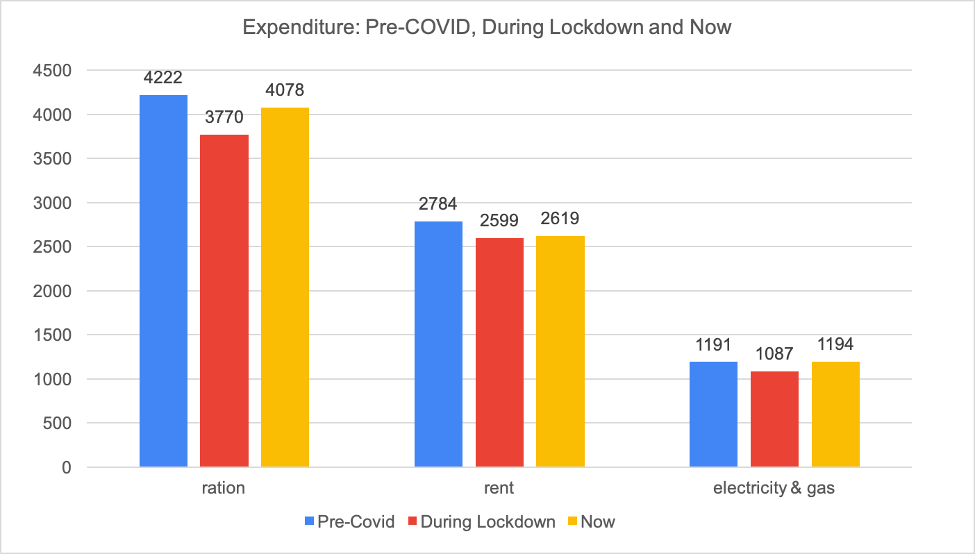

As per our calculations, the average pre-COVID-19 total monthly expenditure for each household in Kapashera was around Rs 10,900. While expenditure did fall by approximately 36% during the lockdown phase, largely due to less discretionary spending, the greater fall in income – due to no employment – left a vacuum that had to be filled with higher borrowings (mostly via informal means).

With a single household earning member (mostly a male), earnings are directed towards feeding the family with roughly Rs 4,200 per month spent on ration alone (during pre-COVID-19 times). Electricity costs are high in Kapashera where electricity is measured through meters for every house or shanty and is chargeable based on per unit consumption (regardless of the condition in which power is distributed to each household). Hence, presence of more electrical appliances leads to significant expenditure on electricity. In terms of utilities, we found every household to have fans and light bulbs; 44.2% had a television; 16.8% an LPG stove, 8.4% a cooler, and only 5.3% a refrigerator.

Where every drop of water counts

Getting access to drinking and non-drinking water is a peculiar struggle for each household – and an expensive one. Water access may not be the most significant contributor to a household’s average monthly expense (compared to rent or ration), nevertheless, it is a vital factor shaping the spending pattern for almost all households, as everyone in Kapashera is required to spend money on procuring water from private sources. It appears as if municipal services are totally absent in the region as a while.

The minimum monthly expenditure on drinking water was found to be approximately Rs 450-Rs 500 per month. Water used for other (nondrinking) purposes such as for washing, bathing and sanitary needs – also known as “gandaa paani” in local language – remains billed through a metric-system reporting an average expenditure of Rs 360 per month. So, on average, almost Rs 860 per month is spent on getting water alone.

Households procure water in three different ways, depending on their needs and financial constraints. Around 77.8% of the households procure drinking water only from treated sources while 13.3% have partial access to treated water. The rest rely on untreated sources such as tanks and ponds provided by private contractors. The treated tap water and untreated water tanks are available within the premises and water jars (costing Rs 10-20 each) are available near the premises for purchase.

Also read: Who Will Nurse the Nurses?

Next comes housing. At the outset, a preliminary visit to Kapashera would see one projecting it as a cosmos for ‘affordable’ living. A migrant earning Rs 5,000-6,000 a month can find a place to stay there and so can someone who is earning over Rs 15,000. Most stay in rental accommodations and rental costs add to the monthly expenditure, roughly being Rs 2,800 on average during pre-COVID-19 times. Due to the financial crisis experienced by migrant workers during the lockdown, in rare cases, respondents mentioned that their landlords decided to let their tenants live rent-free for two to three months. In some cases, landlords simply postponed the rent by a few months.

Aashish, a 31-year-old resident of Kapashera, said: “Kam toh 3-4 mahine nahi chala, factories band thi, hum log baith ke kha rahe the idhar udhar se karza leke. Do mahine ka kamre ka bhada makan malik ne maaf kiya tha, par sashan ki taraf se hamko maddat nahi mili (For almost 3-4 months, the factories were closed and we could not earn any money from wages. We took out informal loans from a few familiar sources in the community to feed ourselves and our family. My landlord did not take rent from me for two months, but other than that there was no aid or monetary support from the government).”

Household debt and the missing state

The high consumption expenditure-led lifestyle for most low-income and middle-income families in Kapashera induced a strong need for households to borrow in a time of crisis.

Institutional borrowing from formal institutions (banks, credit companies) is an expensive option, and often not available to residents of Kapashera due to lack of collateralised assets. Given the low levels of savings, our data reveals that only 6.2% of the households possess any form of fixed assets like agricultural land or consumer durables like two-wheelers on which banks may provide some credit (after a lot of documentation work). Respondents mentioned how they had no option but to resort to intra-community borrowing sources, primarily from family, friends and landlords living in the Kapashera area.

65.5% of the residents said they did not receive any COVID-19-specific aid during the entire period of the lockdown. Non-governmental organisations like IYRC and others provided some help in ration supplies for a while but that wasn’t enough to serve an entire local population of over 10,000.

When asked why the state didn’t help, most respondents said that almost all government aid – mostly referring to ration – was provided to those migrant workers who had returned to their native villages and hometowns during the lockdown. Those who stayed back were largely ignored and left to fend for themselves or receive support from non-state actors. Moreover, anyone who managed to receive some aid criticised the state for doing too little too late. The figure below has more details.

A collective plea: ‘Give me a job and a decent wage’

All chief-wage earners were employed during the pre-COVID-19 period. While many workers were out of jobs during the lockdown, data indicates that 97% of the respondents returned to work after November, indicating some economic recovery. However, despite getting employment, the work in factories, workshops was operating at a diminished capacity with no scope for overtime (which is where most earnings could be made). The fall in working days, overall working hours and the absence of overtime opportunities led to a partial recovery at best which, since the time of the second wave, has been violently disrupted. One doesn’t know how long it will take now for most households to get back to work.

As Munna Singh, a 24-year-old worker, summarises, “Pehle toh ho Rs 12,000-13,000 kamana ho jata tha har mahine, par ab toh lockdown ke baad yahan kaam hi nahi banta hai. Mushkil se 8 ghante ka kaam bhi nahi ho pata, phir bahut chutti bhi ho raha hai (Earlier we were able to earn Rs 12,000-13,000 per month, but since lockdown of last year there is just not enough work. Employers say demand is low. We cannot even keep ourselves occupied for even wight hours a day and end up getting more unpaid holidays due to less working days).”

The aggregate demand problem was afflicting the textile sector even before the pandemic, but a more inelastic supply of export-led goods was keeping most workers (at least those in Kapashera) busy. Now, the absence of economic activity and work opportunities has been exacerbated by the staggered recovery of international trade as well. Survey results depicted that roughly 88% of Kapashera residents worked in the private sector, mostly in export companies dealing with higher end fashion products. Their incomes and livelihoods were directly tied to the global demand of these products which are now being produced in lesser supply.

As Aashish explains: “We used to get bulk purchase orders primarily from countries like the US. When no one orders anything now, how will we get work? (America, aur kai desho se order milta hai. Bahar ke koi order aa hi nahi raha hai toh hume kaam kahan se mile?)”

Reminiscing of better times in the pre-pandemic period, Ashok Singh, a resident at Kapashera for the past 30 years, says, “Pehle kabhi aisa nahi dekha. Lockdown ke aane se yahan bahut saari problem hui, bahut sankat sabko jhelna pada. Corona kaal se pehle sab log acche se kama rahe the, kha rahe the, sukoon se apna zindagi bita kar rahe the. Jabse corono aaya aur lockdown hua tab se kiraidaaro pe musibat ka pahad toot gaya hai (We have never witnessed anything like this before. The pandemic and the lockdown caused many problems and inflicted a lot of misery. Before this, people were earning well, living their life in a peaceful co-existence. Since the lockdown was enforced, the community at Kapashera has been crushed by the crumbling weight of all problems: joblessness, debt-burden etc.).”

The pandemic’s wrath has wreaked havoc on the lives and livelihoods of families living in Kapashera. Those like the ‘atmanirbhar’ migrants of Kapashera desperately need to get back to a working wage – and have a secured employment for subsistence.

Names of all respondents are changed to protect their identity. This study was undertaken as part of a Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES) Visual Storyboard initiative. The authors would like to thank Mr Suraj Kant, founder and director at Ideal Youth For Revolutionary Change (IYRC), for all the support and assistance provided during the project’s fieldwork.

All photos by Jignesh Mistry.

Deepanshu Mohan is Associate Professor of Economic and Director, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES), OP Jindal Global University. Jignesh Mistry is a Senior Research Analyst and the Visual Storyboard Team Lead with CNES. Richa Sekhani, Advaita Singh, Vanshika Mittal are all Senior Research Analysts with CNES. Swati Tiwari is Project Co-ordinator at IYRC.