Visakhapatnam: With folded hands, 22-year-old Satya bows in front of a young tree on a sandy beach in Mangamarepeta, a fishing village in Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh. In the distance, fishing boats are anchored on the beach and heaps of nets dry in the open.

After praying to the tree – which is Satya’s family deity – she narrates the horror of Cyclone Hudhud, which struck her village of 4,500 fisher families in October 2014. “My house was right here on the beach next to the family deity. Although I am a fisher, I had never seen such a ferocious sea, whose hungry waves swept away my house and the tree. I have replanted the deity.”

She takes a moment to remind herself of her good fortune: her husband, a fisherman, and two young children – a 9-year-old son and an 8-year-old daughter – escaped the disaster unhurt.

“Apart from my house, 24 houses of fishers were engulfed by the sea. We received a compensation of Rs 10,000 per lost house, but the cost of my house alone was over Rs 2.5 lakh,” Satya said.

Her family has since rented a house a little more away from the beach, for Rs 600 a month. The 24 other fisher families have moved to rented houses as well.

However, Mangamarepeta’s fishers are far from being content. The sea, their only source of livelihood and sustenance, has been coming further inwards every year, eating into the coastal lands.

Also read: As Mumbai’s Coastal Reclamation Begins, Artisan Fishers Fight for Their Livelihood

“We are facing a double whammy,” says U. Bharati. “On the one hand, the sea is threatening us by coming closer. On the other hand, the fish catch has declined sharply.

“In the next few years, several houses of fishers on the beach will be inside the sea, turning them into refugees.”

Satya is also worried about losing her family deity to the sea once again. “Both the tree and the place on the beach where it is planted are sacred to me. I may lose them both.”

Gain some, lose a lot

Mangamarepeta is one of 555 fishing villages along the Andhra Pradesh coastline. According to a 2016 paper, the state is home to 163,427 fisher families.

According to K. Nageswara Rao, professor emeritus at the department of geoengineering at Andhra University, coastal areas face both erosion and aggradation – the deposition of material.

“The evolution of east coast delta, between Krishna and Godavari rivers, shows that over 6,770 sq. km of delta was created in the last 6,000 years,” Rao recently said at a media workshop in the city. “And this delta progradation continued the till early 20th century.”

East coast delta progradation in 6,000 years. The dark portion beyond the dotted line shows the creation of delta land. Credit: K. Nageswara Rao

However, the coastlines keep changing due both to natural and human-made factors. Rao has recorded shoreline changes along the Andhra Pradesh coast between 1990 and 2008. He “found the state has lost 88 sq. km of coastline due to erosion and gained 40 sq. km by accretion.”

That brings the net area of coastal land lost to 48 sq. km, or 2.67 sq. km of along the shoreline a year.

This isn’t unique to India. A 2018 study reported that the planet lost about 14,000 sq. km of such land between 1985 and 2015 to human settlements and terrestrial ecosystems. India itself has lost 235 sq. km of its coastal area between 1990 and 2016 due to erosion. And between 1965 and 2017, Visakhapatnam lost 54 hectares of beach land along a 10-km stretch.

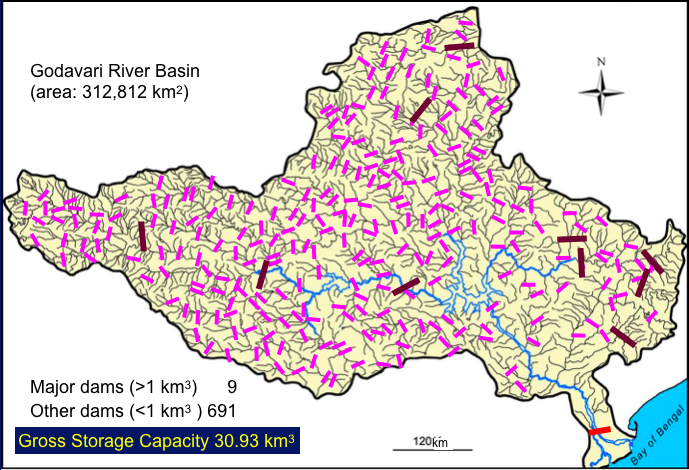

There are many causes of coastal erosion. One of them is the construction of a series of dams on rivers. The dams decrease the flow of water and trap sediments, and slowly sink the delta.

The threat multiplier

“In India, nearly 250 million people live within 50 km of the coastline,” R. Ramasubramanian, principal coordinator of the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Chennai, told The Wire. “More than seven million coastal families of fishers and farmers are threatened due to climate-change-induced sea-level rise.”

Climate change has also caused, and will continue to cause, shoreline erosion, tides and currents and saltwater intrusion. “The Indian coast already experiences severe weather events, such as an average of nine cyclones a year,” he added.

A rising sea is pushing more saltwater inland, and several sources of drinking water in Mangamarepeta have turned saline. Now, the local administration supplies freshwater once or twice a week. The fisherwomen collect 20 pots of drinking water every day and carry them home. They also have to visit the market to sell their catch of fish. Credit: Nidhi Jamwal

S. Venkatesh, a fisheries livelihoods consultant in Kakinada, “Small-scale fishing communities are already facing several challenges, such as uncertain availability of fishery resources, marine pollution, high cost of operation, imperfect market and financial mechanisms, indebtedness.” They don’t need climate change but it’s here, and it threatens to doom their living.

For example, as the ocean’s surface warmed, the distribution boundary of oil sardine – a species of ray-finned fish – changed along India’s coastline between 1961 and 2006. Until about 1976, it was to be found only along the western coast, but by 1997, fishers began spotting it along the entire coastline.

“In Mangamarepeta and surrounding villages, fishers used to catch 24 species of fishes. But now they can barely find four species,” said Arijilli Dasu of the District Fishermen’s Youth Welfare Association, Visakhapatnam.

Pardesi Sarada, a fisher from Mangamarepeta, complains how from a daily fish catch of Rs 5,000, the earnings have dwindled to Rs 500 a day. “The cost of one fishing net alone is Rs 20,000 and needs to be replaced after three months,” Sarada complained.

Also read: A Sip of Sea Water

Satya said her husband used to bring in five or six baskets of fish daily a decade ago but can barely manage three today.

Fisher families have a clear division of labour. Whereas menfolk go to the sea for fishing, women carry the fish catch to market for selling.

“Large motorised boats come from the harbour and remain in the sea for 10-15 days and take away all our fish. Our menfolk have to go deeper into the sea to catch fish. Often, they return empty handed,” Bharati said.

I ask Satya if her children will take after their parents, and she is clear. “Never a fisher. Children should always do better than their parents. There is nothing left in small-scale fishing.”

Nidhi Jamwal is an independent journalist based in Mumbai.