The emergence of “mandatory Aadhaar” for anything and everything – school admissions, public examinations, bank accounts, insurance – has no support in the Aadhaar Act.

Women stand in a queue to get themselves enrolled for the unique identification database system in Rajasthan. Credit: Reuters/Mansi Thapliyal

The ongoing final hearings in the Aadhaar matter are probably second in importance only to the drafting of the constitution. While this exercise has opened up an opportunity to delineate the boundary between the state and the citizenry, it may be moot to also examine how this quest for the “ultimate prize” is playing out in the courtroom, and also whether the existing law is sufficient to impart some sanity to the Aadhaar madness.

The emergence of a surveillance state

The dominant theme in all the Aadhaar hearings has been the Orwellian ambitions of the government to demand from the citizens utmost transparency in every transaction or activity via-a-vis the government. The ‘opening statement on behalf of the petitioners’ in the ongoing hearings likened Aadhaar to an “electronic leash” that tethers every citizen to the government. It also raised the question whether it is reasonable for citizens to expect that they have a choice in the manner of identifying themselves to the government.

While the government’s response is yet to commence, the past hearings give a good indication of what it is likely to be – that there is no ulterior motive (like surveillance) behind the carpet-bombing of Aadhaar and that Aadhaar is necessary to achieve the goals of good governance.

The court is, therefore, called upon to decide on the limits of the power conferred by the constitution on the state. While there is much hope among those who are determined to see the end of Aadhaar, past experience could at best be called neutral.

When the Aadhaar case was heard last in December 2017, the court was called upon to give interim relief. While the order dated December 15 extended all Aadhaar linking deadlines to March 31, 2018, it should still be considered an interim victory for the government, because it essentially sanctified all the Aadhaar notifications issued over the preceding two years (though as an interim measure). In effect, the interim order from October 2015, which restricted the use of Aadhaar to five schemes, that too in voluntary capacity, was rendered nugatory, even without going into the merits of the case.

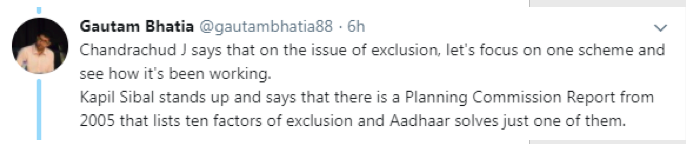

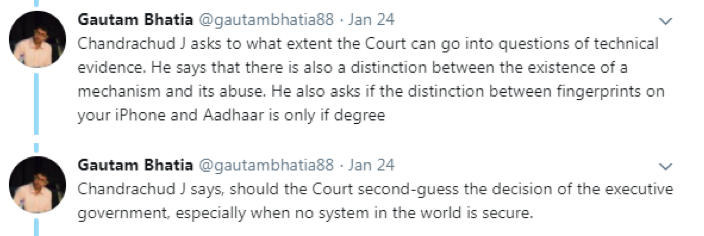

The present hearings also give an indication of which way the court may be tilting.

Chandrachud J says that we live in times of terrorism and money laundering and welfare expenditure, and this has to be balanced.

He says that surveillance is about how data is used, not collected.— Gautam Bhatia (@gautambhatia88) January 24, 2018

In normal circumstances, this should not come as a surprise, because the elected executive government is expected to have the wherewithal (and, therefore, the competence) to decide on matters of policy. The court would need extraordinary evidence to take the risk of derailing what the government considers central to its governance stratagem.

In these circumstances, is it possible to reduce the burden on the court by narrowing down the arguments to two principles – one, whether government action is backed by a law, and two, provided the first is true, whether such law is in consonance with the constitution.

The widespread use of Aadhaar appears to emerge from Section 57 of the Aadhaar Act.

SD points to Section 57, which allows the use of Aadhaar to establish identity for any other purpose.

— Gautam Bhatia (@gautambhatia88) January 23, 2018

Let us examine what Section 57 says:

Nothing contained in this Act shall prevent the use of Aadhaar number for establishing the identity of an individual for any purpose, whether by the State or any body corporate or person, pursuant to any law, for the time being in force, or any contract to this effect:

Provided that the use of Aadhaar number under this section shall be subject to the procedure and obligations under section 8 and Chapter VI.

“Nothing contained in this Act shall prevent…” A plain reading of this only conveys that Aadhaar is one more identity document that has emerged in the marketplace. Nowhere does it convey any powers to make it a mandatory requirement, a privilege that is the sole preserve of Section 7. Therefore, the emergence of “mandatory Aadhaar” for anything and everything – school admissions, public examinations, bank accounts, insurance, etc. – has no support in the Aadhaar Act.

Some of the most glaring transgressions are the CBSE circulars for JEE and NEET. While these appeal to Section 57 of the Aadhaar Act, they use phrases like “shall enter Aadhaar number” and (for those not yet enrolled) “are hereby required to make application for Aadhaar enrolment”, clearly arrogating to themselves the powers under Section 7.

Another important constraint emerging from Section 57 is that it mandates the use of Aadhaar number only in the manner specified by Section 8, which talks about verifying an Aadhaar number through authentication. It basically extends Section 4(3), which specifies the only manner in which the use of the Aadhaar number is conceived in the Aadhaar Act. Section 4(3) reads as below:

“An Aadhaar number, in physical or electronic form subject to authentication and other conditions, as may be specified by regulations, may be accepted as proof of identity of the Aadhaar number holder for any purpose.”

It is clear that the Aadhaar Act conceives the use of the Aadhaar number only as a proof of identity; further to it, only subject to authentication. Therefore, the requirement to merely submit the Aadhaar number in various forms, or seed it in various databases, is again without any supporting law.

The worst illegality is that in many quarters the “original Aadhaar card” and later-day improvisations like e-Aadhaar and mAadhaar are being accepted as standalone identity documents, even with the blessings of the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI). The circular to this effect, while quoting Section 4(3), throws to the wind the crucial requirement of authentication.

“Authentication”, in the context of Aadhaar, needs some deconstruction. It is not to be seen as a mere ritualistic exercise of doing “some transaction” against the records in the central Aadhaar database – the CIDR. To understand this better, a brief description of the design fundamentals of Aadhaar will be helpful.

Also read: Aadhaar Isn’t Just About Privacy. There Are 30 Challenges the Govt Is Facing in Supreme Court

The raison d’être of Aadhaar is to provide a unique identity to every resident of India and also that such identity be verifiable as genuine, when claiming proof of identity. Only then can the objects of weeding out fake/ghost identities and plugging of leakages in government expenditure be achieved. The UIDAI has fleshed out the underlying design principle of Aadhaar in its filings in the Shanta Sinha case:

“The possibility of a fraud within the system gets checked the moment a person enrolls into Aadhaar system with his or her biometric information including fingerprints and iris scan whereby every time the said person authenticates, the response will confirm that he or she is the person who he or she claimed to be and not any other person. Therefore the said person cannot claim any benefit on behalf of anyone else.” – para 47 (page 55) of the sur-rejoinder dated July 3, 2017.

The above statement is the correct representation of a biometric identity system, where collection of biometrics at enrolment is useful only if the same is verified when claiming the identity. Biometric de-duplication and biometric authentication are like two ends of a bridge and hence cannot be seen in isolation.

For practical reasons, the UIDAI has climbed down from the high horse of biometrics and begun to hold “authentication” through mobile OTP on par with biometric authentication. What does mobile OTP verify other than the existence of an Aadhaar number and a mobile number linked to it? It says nothing about the uniqueness/genuineness of the identity behind it and, hence, is effectively a free pass to Aadhaar numbers that may be generated through any fraudulent means.

The UIDAI has consistently spread the misconception that the law is accommodative enough to safeguard anyone from wrongful exclusion. Credit: Reuters

It is facile to argue that the enrolment stage can ever be secured so tightly that there will be no fraudulent entries at all. The UIDAI’s own design (detailed above) places the burden of countering fraud at the delivery end, which is biometric authentication. The recently exposed racket in Uttar Pradesh, that had successfully created thousands of fake Aadhaar IDs against bogus biometrics, coupled with the fact that nearly 50,000 enrolments operators have been suspended for violation of process guidelines, is mounting evidence that the enrolment stage is open to compromise. The UIDAI’s wilful violation of its own design is again an abject illegality, whose only purpose is to enable the survival of Aadhaar and offers no explanation as to how unique identity will be achieved sans biometric authentication.

In the same breath, Section 139AA of the Income Tax Act should be considered a defective piece of legislation, because it fails to use the Aadhaar number as per the scheme of the Aadhaar Act (i.e. verify through biometric authentication), even while drawing its definition from the same Act. The assumption that the mere linkage of Aadhaar numbers to another database will lead to the “weeding out” of fake/duplicate entries has no basis in law.

Biometric identity being probabilistic rather than deterministic

At the core of Aadhaar lies biometrics and it does not take much imagination to understand that biometric technology is not an exact science, hence cannot provide guarantee of identity. This aspect has been raised during the present hearings.

SD: The issue is this. If I have certain rights, then how can my enjoyment of those rights be made probabilistic?

— Gautam Bhatia (@gautambhatia88) January 17, 2018

Para 6 of the ‘Main Heads of Challenge’ says: “The project is not an ‘identity’ project but an ‘identification’ exercise. Unless the biometrics work, a person in flesh and blood, does not exist for the State.”

On the other side, the government’s consistent defence of Aadhaar has been that it furthers the right to identity, especially for the weakest and most marginalised sections of our society. From its filings in the Shanta Sinha case:

“Aadhaar Act 2016 is an initiative to recognize and further the fundamental right to identity which would provide identification for each resident across the country and would be used primarily as the basis for efficient delivery of welfare schemes. Therefore, when such a measure is taken in furtherance of Article 21, it would be futile to argue that it has no constitutional sanction.” – para 7(h) (pages 20-21) of the Counter Affidavit dated June 6, 2017.

Therefore, there is a great curiosity to understand how the linkage of Aadhaar to welfare schemes is causing huge exclusions, even in the presence of a statutory framework – the Aadhaar Act.

Also, the aspect under discussion being technical in nature, there is a palpable resistance from the court to make a value judgement. Even when the most obvious security risk with biometric systems – that of biometrics getting skimmed – was raised, the response of the bench was pretty nonchalant.

Faced with such a situation, it is necessary to try and unravel how the statutory framework of Aadhaar reconciles with a probabilistic and unpredictable system of identity, emerging from the characteristics of biometric technology. The answer lies in Section 31(2) of the Aadhaar Act:

“In case any biometric information of Aadhaar number holder is lost or changes subsequently for any reason, the Aadhaar number holder shall request the Authority to make necessary alteration in his record in the Central Identities Data Repository in such manner as may be specified by regulations.”

While it may not be apparent at first glance, the entire edifice of Aadhaar as a proof of identity grows out of the above section.

Changes to biometrics are not cognizable events (unlike change of demographic details) that the individual concerned can take note of and take appropriate action. Section 31(2) effectively transfers the entire burden of proof of identity (and consequent uncertainty) on the Aadhaar number holder, by making it a duty on them to keep their biometric records up to date in the database. This is not a duty that can be discharged with any predictability.

An individual will most likely realise the need to update biometrics only after facing an authentication failure somewhere. There may be a variety of reasons why biometric authentication may fail. Old people may have wrinkled fingers, manual labourers may have worn out their fingerprints, there may be people afflicted by various skin ailments or cataract in the eyes… the list is long and open. It is also possible that biometrics may not have been recorded correctly at the time of enrolment. There is also a temporal dimension to biometrics. A 70-year-old man may encounter authentication failure within weeks of enrolment, while a 40-year-old may face the same after five years; nothing can be said for sure. In all these cases, the only recourse available is to update the biometrics. This is precisely what explains the exclusion and harassment faced by those who land up on the wrong side of biometric authentication.

Another way to look at the above is that Section 31(2) is in violation of Article 14, because it divides the Aadhaar enrolled population into two parts – one whose present snapshot of biometrics matches the records in the database and another whose does not. This division is neither intelligible, nor well-defined, nor static. An identity system grounded in an Article 14 violation must also necessarily compromise Article 21 (the right to identity).

Also read: A Pakistani Spy and Lord Hanuman Walk Into an Aadhaar Centre. What Does the UIDAI Do?

The plot stands completely exposed in the way the Aadhaar (Enrolment and Update) Regulations, 2016 implements Section 31(2). Regulation 19(a) reads as below:

The process of updating residents’ information in the CIDR may be carried out through the following modes.

At any enrolment centre with the assistance of the operator and/or supervisor. The resident will be biometrically authenticated and shall be required to provide his Aadhaar number along with the identity information sought to be updated.

Biometric authentication is sought as a necessary precondition, before accepting a request for update of biometric information. It may be too risky to relax this precondition because it would then be open for anyone to replace anybody else’s biometric profile. So, there is a distinct possibility that someone caught in the tight loop of biometric failure may find themselves permanently locked out of their Aadhaar identity.

The UIDAI has consistently spread the misconception that the law is accommodative enough to safeguard anyone from wrongful exclusion.

There they go again; the Aadhar law provides that if Aadhar does not work for some, other identities should be used; but for leftists malcontents this matters not;they want to keep bashing Aadhar @NandanNilekani https://t.co/jT4n9TOXi6

— Mohandas Pai (@TVMohandasPai) January 27, 2018

The Article 14 violation noted earlier is relevant here, because the category of people for whom “Aadhaar does not work” is neither bounded nor static, so the provision of alternatives (whether other identities or non-biometric authentication modes like mobile OTP) must be kept open to all, effectively leaving the field as much open to fraud as earlier.

The surveillance argument also grows out of here, because all efforts are being made to universalise Aadhaar, even at the expense of losing sight of its core purpose, which is to provide a unique and verifiable identity.

It is, therefore, possible to break down the Aadhaar case into a set of legally verifiable questions, thereby lending some much-needed predictability to the course of the proceedings. The biggest evidence at hand is the Aadhaar Act itself, because it puts down in writing what was earlier in the realm of apprehension. Bringing into question the intent of the state is tantamount to asking the court to deliver political justice, which would be as undemocratic as a runaway government.

L. Viswanath is an engineering professional based in Bengaluru. He blogs at bulletman.wordpress.com.