When the tongue pulsates,

Tone manumits the air, and

Song turns missile in battle

The foe fears the poet;

Incarcerates him, and

Tightens the noose around the neck

But, already, the poet in his notes

Breathes among the masses…

Octogenarian poet, literary critic, rights activist, academic, public intellectual and Maoist ideologue Varavara Rao, endearingly known to his followers as VV, wrote these lines in his poem Kavi, (‘The Bard’) published in a collection prophetically called Bhavishyattu Chitrapatam (‘Portrait of the Future’) in 1986.

The fire of revolution that was kindled in him by the Naxalbari movement when he was a young lecturer fresh out of university, has remained unextinguished for six decades and continues to scatter ashes and sparks, igniting flames that can burn entire prairies of neo-liberalism, repression, casteism and religious dogma. It’s no wonder that a state which shows a clear affinity for fascism and seeks to smother all forms of dissent, considers him a foe, and fears and incarcerates him.

A deep commitment to revolutionary humanism runs through Varavara Rao’s literary oeuvre containing some 15 volumes of poetry, letters, translations (including that of noted Kenyan author Ngugi Wa Thiongo) and literary criticism. He is one of the most important Indian poets of the second half of the 20th century, a claim backed by the translation of his works in almost all major Indian languages.

He is an equally powerful Marxist critic of literature and arts. His poetry springs from his lifelong political activism and his politics and poetics complement each other in a poignant, authentic way. In the mid-1980s, VV was charged with hatching a conspiracy with the Naxals to kill a police officer and supplying explosives for the act. Sitting in Warangal prison, he wrote:

“I did not supply the explosives

Nor ideas for that matter

It was you who trod with iron heels.

Upon the ant-hill

And from the trampled earth vengeance was born.

It was you who struck the bee-hive

With your lathi

The sound of the scattering bees

Exploded in your heart”

The charges against VV were never proved. Scroll.in reported that between 1973 and 2018, as many as 25 cases relating to his role in Maoist insurgency have been lodged against Varavara Rao and not one of them has been proved in court. On August 28, 2018, he was arrested from his home in Hyderabad for his alleged role in a plot to assassinate Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Also read: ‘Attack on Varavara Rao Is an Attack on All of Us’: Young Poets Urge Release of Activist

While arresting him, police officers allegedly asked his family members why there were so many books in his house, particularly on Marx and Mao, and why there were photos of Ambedkar, but not of gods. His niece Varsha Gandikota Nellutla writes in this Boston Review essay that “the goal of Narendra Modi’s administration has been to silence those like my uncle… To the Indian government, he’s a rebel and a threat, an ‘anti-national’.”

Obtaining a master’s degree in Telugu literature from Osmania University, Rao founded a literary group called Saahithee Mithrulu (Friends of Literature), which started bringing out a journal called Srjana in 1966. Around the same time, he announced his arrival in the Telugu literary scene with two collections of poetry written mostly in free verse: Chali Negallu (‘Camp Fires’) in 1968 and Jeevanaadi (‘The Pulse’) in 1970. Srjana began as a quarterly journal, but its immense popularity prompted VV to bring it out monthly from 1970, and include writings on social justice.

From the very first issue, it gave a voice to the voiceless. VV was associated with Srjana till 1990. During his long and repeated prison terms, his wife, Hemalatha, edited the magazine. Around the same time when VV was first arrested in 1973 under the draconian MISA Act, a number of issues of the journal started getting banned. In an interview with webzine Raiot.in, VV said, “During this time (1972-74), six issues of Srjana were proscribed under sedition. During the railway strike in May 1974, Srjana published a poem “can jails run the rails” by a railway worker and wrote an editorial under the same heading. It was banned.”

While outrage and resistance have been driving forces behind VV’s poetry, his poems have never become desperate rants, thanks to his genuine commitment to an ideal, his deep pragmatism, his avant-garde tendencies, constant use of irony and metaphors, and what many readers have felt to be a romantic strain. No Indian poet, it can be safely said, has written more while in prison, than Varavara Rao. During his very first imprisonment in 1973, he wrote

“This is jail for the voice and the feet

But the hand hasn’t stopped writing

The heart hasn’t stopped throbbing

Dream still reaches to the horizon of light

Travelling from this solitary darkness…”

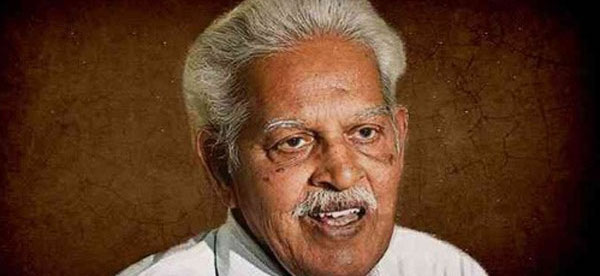

A file image of Varavara Rao.

Bhavishyathu Chitrapatam (‘Portrait of the Future’, 1986), and Muktakantam (‘Free Voice’, 1990), have been the two most celebrated volumes in VV’s poetic corpus. Police atrocities during the NTR regime, anti-people policies of the government, extra-judicial killings and the issues of the marginalised people of Andhra Pradesh are recurring themes in these volumes. ‘Butcher’, in the 1986 volume is point-blank in its condemnation of torture of civilians in police custody. A Muslim butcher had witnessed the killing of a college student by police in full public view on May 15, 1985, because he was asking shopkeepers to down their shutters in protest against police encounters. The butcher in the poem said,

“I too take lives

but never with hatred

I do sell flesh but

I have never sold myself”

Marvellously poignant and hard-hitting is the poem ‘Dance of Liberty’ in the same volume, where VV plays with the metaphor of Spring after home minister Vasanta Nageswara Rao announced that the state championed liberty and peace. No wonder the collection was banned.

Also read: Chained Muse: Notes from Prison by Varavara Rao

The lyrics in Muktakantam are some of the very best that VV ever wrote. In ‘After All You Say’, he sees the act of writing as an endless movement:

“For me

The scene of writing,

Torsioning out word-chains,

From the seams of the earth,

An endless movement.

In writing too

Pressure and stress inflecting sounds,

Repeated in a weave of inter animation.

Force re-gendering

Words

As lines of people,

In-surge in movement.”

‘Words’ talks about VV’s own poetic vision; how he stirs awake words from his soul, and then they soar into the sky: ‘Once again I must learn to utter/In communing with and listening to/Our people;/I must be tethered to the word and abide by it/What’s man’s legacy after betraying the word?’

In 1970, inspired by Naxalbari, VV founded the Viplava Rachayitala Sangham (Virasam) or Revolutionary Writers’ Association, along with author Kutumba Rao, dramatist Rachakonda Viswanatha Sastri, poet and historian K.V. Ramana Reddy, Jwalamukhi, Nikhileswar, Nagna Nuni and Cherabanda Raju (known as Digambar poets) and a few others. For half a century it has spearheaded the Dalit literary movement in South India. Its official journal Aruntara has been a platform for the youth, particularly Dalit writers, to record their resistance to the massive semi-feudal centre and its totalising systems.

Just as VV the poet has created a space where silenced voices, those of a butcher, a railway worker, an Adivasi, a landless peasant, an encounter victim can be heard, VV the editor opened up the literary scene for Muslim and Dalit writers and women in the 1970s and 80s. The publishing cell of Virasam has brought out nearly 100 books by these writers, which contain short stories and poems on subjects like the Dandakaranya movement, Operation Green Hunt or custodial death of Adivasi men. Many of these works have been translated into English other Indian languages.

In 2010, Penguin India published a collection of VV’s letters ironically entitled ‘Captive Imagination: Letters from Prison’. In the foreword, the author says the pieces in the book are “notes… scribbled in the loneliness of jail”. Explorations of solitude and confinement is the central theme of the letters culled in the volume, with VV showing that no jail in the world, big or small, can hold a poet’s imagination captive.

Also read: ‘No Reason in Law or Conscience to Hold Varavara Rao’, Say Academics in Appeal

VV’s other major prose work is his PhD thesis entitled ‘Telangana Liberation Struggle and Telugu Novel – A Study into Interconnection between Society and Literature’. It is by far the best known critical work on the influence of Marxist literary theory in Telugu fiction. It set forth a tradition of literary criticism in Telugu carried on by the likes of C.V. Subbarao, K Balagopal, N. Venugopal Rao and K. Srinivas.

VV’s poetry, which records a third-world reality crisscross with the most unending, brutal poverty and his vision for a world free of exploitation, has sustained his larger-than-life character for over half a century. His commitment to revolutionary humanism is a real, serious one, and successive governments, both in his home state and at the Centre, have relentlessly tried to muzzle that commitment. Touching 80, and suffering from multiple ailments including COVID-19, he remains the state’s Enemy No. 1.

May he continue to breathe among the masses! Long live the revolution! Long live VV!