This is the second of a four-part series on Shah Inayat, whose 300th death anniversary is now being commemorated. Read the first part here.

The popularity of Sufi Shah Inayat’s movement not only lead to the reduction in the number of devotees of Saadaat family, but the peasants of Babu Paleja and the surrounding areas were also affected. “The fakirs of Sufi Inayat were also mischief-making in their lands, meaning they were preaching collective farming.” The result was that landlords’ peasants began demanding that the method of Sufi Shah Inayat should also be practiced in their lands. But the landlords were not prepared to accept the principle of equitable participation in production.

They had felt that unless this revolutionary mischief was not dealt with immediately, the feudal and landed system in Sindh would fall in danger. So in order to stem the danger, the landlords – among whom Syed Abdul Vasay, the heir to Shah Abdul Karim of Bulri; Sheikh Sirajuddin, the heir of Sheikh Zakariya Bahauddin; Noor Muhammad bin Manba Palijo and Hamal bin Laakha Jaat, landlords of Palejani were in the forefront – pleaded with Mir Lutf Ali Khan, the subedar of Thatta to prevent Sufi Shah Inayat from collective farming. But Sufi’s land had been forgiven by the state – this was a special category of land which was granted to schools and madrasas for their expenditure or to ulema, scholars and the family of saadaat for their subsistence as forgiveness. The subedar had no authority over it. So he did not find it suitable to intervene from the side of the government, and instead gave the landlords permission to deal with the Sufi and his fakirs as they wished.

At the cue of the subedar, the landlords suddenly attacked the town of Jhok but were defeated disgracefully – although many fakirs were killed and people suffered huge financial losses. The heirs of the martyrs filed a suit in the royal court against this lawlessness of the landlords; the court ordained that: “The criminals should give an account of the blood of innocents in the presence of the king. Because they violated the royal decree, therefore in lieu of blood money according to the royal constitutional act, their lands were given to the heirs of the slain.”

The spirits of peasants on all sides rose with this legal victory of the fakirs and the terror of official authorities and landlords also no longer remained as of old, in fact:

“Most of the poor and the rest of these districts began to live peacefully in the protective refuge of this man of God (Sufi Shah Inayat) after their deliverance from the oppression of the landlords.”

Also read: Remembering the Socialist Sufi of the Indus Valley, Shah Inayat Shaheed

This tells us that the peasant movement of Sufi Shah Inayat had spread to many districts in lower Sindh and because of the support of the Sufi, the people had become so powerful that the landlords could not dare touch them. Meanwhile, “the number of fakirs distressed by the oppression of the time also began to increase day by day and calls of Hama Uust (God is Everything) began to rise from every nook and corner, dome and monastery.”

Perhaps Farrukhsiyar, thinking that Mir Lutf Ali Khan was treating the fakirs leniently, replaced him in 1716 with Nawab Azam Khan as the subedar of Thatta. The landlords took advantage of this change and began to poison the ears of Azam Khan by backbiting. Maybe the nawab had personal ill-will against Sufi Shah Inayat as well. It is said that once when Azam Khan went to meet Sufi Shah Inayat, the fakirs stopped him saying that the former is busy in chanting and reading some special verses from the Holy Quran. When they met, the Sufi Azam Khan said that, “It does not behoove an ascetic to have guards at his door.” The Sufi unhesitatingly replied that, “It is appropriate so that a worldly dog may not enter.” This matter became the cause of a personal grudge for Azam Khan.

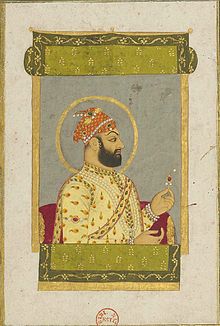

Emperor Farrukhsiyar. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

This tradition maybe right or wrong, but Nawab Azam decided to crush the movement for collective farming and began stoking the flames. He demanded dues from Sufi Shah Inayat which had been “forbidden by the sovereign”. The Sufi responded by saying what right of collection do you have when these dues have been forgiven from the king. The nawab was agitated with this answer. He wrote a complaint to the king after consulting his deputies and executive officials that Sufi Shah Inayat and his fakirs were claimants to the throne and refusing to follow the orders of the caliph of Allah. Farrukhsiyar, without investigating this incidental matter ordered the rebels to be forced to obey at the point of the sword.

Siege of Jhok

Immediately after getting permission from the Centre, Nawab Azam Khan began preparing for an assault on Jhok. He sent orders to virtually all the nobles of Sindh to assist him with their soldiers.

“(Azam Khan) had secured orders of assistance to Mian Yar Muhammad Kalhoro, all the landlords and all the people of this region who had old enmity with the fakirs. So he attacked the fakirs by assembling such an army the likes of which could not be counted and was even greater than ants and locusts and had been gathered from Sibi, Dhadar and the area upto the sea.”

Sufi Shah Inayat was a peace-loving sage. When he heard about the opposition of the landlords and the military preparations of Azam Khan, he became sorrowful that, “I had not brought this trade in the bazaar of love for all this and neither did I want that such uproar be created so as to prepare a field of conflict.” When the armies of the enemy moved towards Jhok, the fakirs presented a proposal that why don’t we attack them on their way so that the royal army does not have an opportunity to arrange its ranks and Jhok be spared from siege but ‘the God-conscious Shah did not allow forestalling.’

Jhok was a peaceful settlement of fakirs, not a military cantonment. Apart from their “paper” swords which had wooden handles, any arms which they had were a small wooden cannon, whereas the enemy was armed with “iron cannons used to kill elephants”. But from the letters of Mian Yar Muhammad (the ruler of Bukkur Khudayar Khan Kalhora) and Meeran Singh Khatri Multani which had been written from the battlefield, it seems that as per the ancient tradition, strong ramparts of raw earth were present around Jhok and a deep ditch was also dug which was filled with water.

Also read: Karl Marx: The Passing of a Colossus

The letter which Mian Yar Muhammad had written in Farsi to his son Mian Noor Muhammad during the siege informs that the royal army reached Jhok by departing from the Uthal River on October 12, 1717 or a few days before; and settled at a distance of one mile from the settlement, although the number of invaders and fakirs could not be known. It is known from the letter of Meeran Singh Khatri Multani that “the party of Nawab Azam Khan was small” and fighting actually took place between the huge army of Khuda Yar Khan and the fakirs. He writes that the “fortress of mischief” was besieged on one side by Khuda Yar Khan “guns which threw lightning and islands which made thunder-like confounding noise began to punish the enemy” and on the other side Nawab Azam Khan set up a fortification and “raised an uproar of war with arrows.”

Tomb of Mian Yar Muhammad Kalhoro. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Meeran Singh has clarified the military superiority of his benefactor Mian Khuda Yar Khan and the inferiority of the royal army with great prudence. He narrates the party of fakirs to be 10,000 riders – which is inaccurate. What to talk of horses, they even did not have so many men. Mian Yar Muhammad has written in his letter while narrating the night-attack by the fakirs that the latter were 1,700 afoot in number that “in reality the spirit of all the mischief-makers existed.” One can speculate from this that the total number of fakirs was no greater than 2,000-2,500 and they did not possess firearms at all.

The night attack

The incident of the night-attack took place on October 12, 1717 on the same night as the day the royal army besieged Jhok. Mian Yar Muhammad writes that:

“It was Sunday night. Our army had laid siege. Still three hours of night remained that 1,700 of the mischief-makers somehow reached the army on foot with the intention of a night-attack and advanced into the army at many places and began to attack without fear or hesitation, so many men of the army fell in battle although our braves bent over backwards to prove themselves and only a handful of mischief-makers were able to escape with their lives.”

Also read: The Changing Face of Sufism in South Asia

“In this night-attack, most of the Panhwar among Qasim son of Gohram and Syed Bola, lawyer of Thatta and Ahmed Bobkani and our brothers of the Odhija nation and other landlords as well were killed.”

When this attack took place, the soldiers who were appointed for guarding near the tent of Mian Yar Muhammad ‘went here and there’ (perhaps deliberately) but it was all well that the two sons of Mian Yar Muhammad, Mian Dawood and Mian Ghulam Hussain, and his brother Mir Muhammad ibn Mian Naseer Muhammad were present at the scene of the incident. In the ensuing battle, Mian Ghulam Hussain was injured.

Two months passed during the siege but the royal army despite being armed with cannon and gun dared not capture Jhok. Meanwhile, Sahibzada Syed Hussain Khan and several landlords reached Jhok with the reinforcements as per the order of Nawab Azam; but perhaps at the same time a flood came and “there was such an abundance of water around the ‘fort’ of Sufi Inayat that no trace of land could be seen for four or five miles.” Nevertheless, Sahibzada’s army crossed the water somehow and set up a fortification near the ramparts of Jhok. Mian Yar Muhammad, while singing odes to this unparalleled achievement of his able son scatters pearls in such a way as if the hero had emerged victorious in the seven labours of (ancient Persian hero) Rustom.

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic, and an award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently teaching in Lahore. He is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. His most recent work is an introduction to the reissued edition (HarperCollins India, 2016) of Abdullah Hussein’s classic novel The Weary Generations. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com