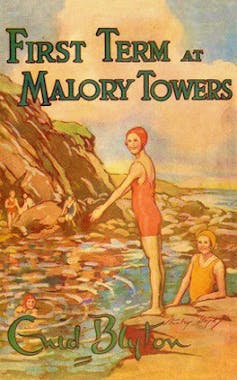

While UK schools are closed for the majority of children, Malory Towers has opened its doors in a new adaptation on BBC iPlayer. Its source text, Enid Blyton’s First Term at Malory Towers (1946), was the first in a series of six, and very much a product of its time.

The clifftop setting was inspired by Benenden School, which Blyton’s daughters attended, and which temporarily relocated from Kent to a hotel in Cornwall during the Blitz. This idyllic landscape sets the mood for the novel, which is steeped in ginger beer and post-war optimism. Now, in a time of national emergency, the series promises both nostalgia and escapism, a welcome distraction from the pandemic.

Also read: Enid Blyton, Moral Guide

The title sequence fulfils these promises: bathed in the rose-tinted glow of retrospect, it features a world of pillow-fights, lacrosse matches, and friendship. Yet this saccharine opening belies the series’ revisionist impulse, which is as concerned with diversity, neurodiversity and gender equality as it is with hoodwinking Matron for extra tuck.

It’s widely accepted that adaptations reveal as much about their contemporary contexts as their literary sources, but this is more than a simple updating. Rather, the BBC’s Malory Towers reveals aspects of the historical context that were glossed over in Blyton’s novel, finding its inspiration in the gaps and silences of the original.

Diversifying the cast

The first change is evident in the girls themselves. The first form is a mix of white and BAME girls. There is also body diversity, with girls of all sizes and one with facial disfigurement. This upholds the standard set by Emma Rice’s 2019 stage adaptation, which cast a non-binary trans actor and one with restricted growth, as well as two women of colour.

The first edition of the novel, illustrated by Stanley Lloyd. Photo: Wikimedia

The same year, a four-novel reboot, New Class at Malory Towers, introduced black, Asian, introverted and working-class characters to the school.

The illustrations to the first edition of Blyton’s novel, conversely, paint a blandly homogeneous picture. Given that children from the Commonwealth were often sent to English boarding schools, this seems like straightforward whitewashing.

The series puts that right, reflecting how, in the words of adaptor Sasha Hailes, 1940s “Britain [was] more diverse than it’s often accounted for”.

Learning differences

The book’s homogeneity also extends to learning differences, of which there are none: only girls who don’t try, and “stupid ones”. “If you are brainless and near the bottom, we shan’t blame you, of course,” says housemistress Miss Potts, in a pep talk bordering on disciplinary offence. “But if you’ve got good brains and are down at the bottom, I shall have a lot to say.”

Two girls fall into the latter category: governess-reared Gwendoline, who phones it in for half the term before discovering the existence of school reports, and heroine Darrell Rivers. Darrell is able but struggles with arithmetic. Being distracted by the class clown causes her to fall in the class order before she hoists her socks with military enthusiasm and finishes fifth from the top.

In the series, however, Darrell has a genuine struggle with spelling and presentation, rising hours before the others to make clean copies of her jumbled prep. Devastated when her class position fails to reflect her hard work, she volunteers to be put in the “dreaded remedial” class. There, tutor and head-girl Pamela diagnoses “word-blindness”, or modern-day dyslexia. As a representative of the countless children with learning differences throughout history, Darrell is a role model for neurodiverse viewers. Her coping strategies, and a renewed commitment to becoming a doctor, also model an admirable growth mindset.

Choice above all

Darrell’s interest in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects, and her belief that “girls [can] do everything boys can do”, shows how the series amplifies the feminism of the book. This is largely a product of its single-sex environment, which offers a safe space for the girls to develop, free from the need to conform. The book’s feminism is, however, offset by Blyton’s tendency to downplay academic achievement.

Miss Potts and lead character Darrell. Photo: BBC/WildBrain/Queen Bert/Steve Wilkie

For Miss Potts, the most successful old girls are not “those who have won scholarships and passed exams” but those who have become, more nebulously, “good, sound women the world can lean on”. This bodes ill for “clever Irene”, who is “a marvel at maths. and music, usually top of the form – but oh, how stupid in the ordinary things of life”. Darrell, by contrast, is said to have “the makings of a first-rate person”, combining academics with games prowess and lashings of common sense.

The series inserts several narratives that champion academic achievement, the pursuit of a career and above all a girl’s right to choose her own path. Sally is sent to Malory Towers, not so her mother can focus on her delicate sister, as in the book, but to prevent her from becoming an unpaid carer and wasting her academic potential. Emily, whom Blyton describes as “a quiet studious girl”, has her education funded in the series by her mother’s work in the school’s sanatorium. Meanwhile Pamela chooses in a new storyline to debut in society, instead of pursuing a teaching career, in the hopes of safeguarding her family’s estate. “Maybe [teaching] isn’t my dream,” she tells an incredulous Darrell, “we can’t all be pioneers”. The message is confirmed by Miss Potts when Gwen suggests that she, too, would prefer society to college: “You’re lucky to have a choice”.

For fans of the adaptation, the series has now been novelised by Narinder Dhami as Malory Towers: Darrell and Friends. It is available to purchase alongside Blyton’s originals, Pamela Cox’s sequels, and New Class at Malory Towers, giving young girls, and boys, that most valuable of things: a choice.

Bethany Layne, Senior Lecturer in English Literature, De Montfort University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.