“At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom,” announced Jawaharlal Nehru as the world ushered in a new nation, the echoes of the distraught mere echoes amidst the joy of freedom.

Well, as they said, what do people wearing white caps sitting in Delhi know about the situation at the border? The Partition of India, a cataclysmic event which gave birth to the world’s largest democracy, left a devastating legacy and scars that refuse to heal.

Even after 72 years and three generations, a part of its legacy still thrives within us; the remnants of the separation still haunts us. While having a casual discussion with a fellow Punjabi about her maternal grandmother’s yearning for her beloved erstwhile home, the shared belonging and collective memory reverberated.

Finding no recluse under the infamous ‘Dilli ki garmi’, my mind drifted to Holocaust survivors who shared narratives of the ghastly apocalypse. Borders, after all, are simply political boundaries. Beyond the demarcations, it is land; vast land, full of flesh and blood, of thoughts and emotions, of common folklore, myths and superstitions.

Well, as they say, ‘Batwara jitna bhi kar lo, garmi Lahore Dilli dono mein paintalis hi padegi’. (Divide as much as you want, the heat in both Lahore and Delhi will be 45 degrees Celsius).

Narrating the tale of the Samjhauta Express, a brief encounter with investigative journalist Bhavna Vij Aurora led to a shattering of stereotypes and infused biases as a major societal consequence of the Partition. As a Punjabi, being accompanied by a Muslim cameraman to Pakistan seemed like a logical step to her. As it turned out, it wasn’t!

She felt closer to ‘their Punjabi’ more than the cameraman did as a Muslim.

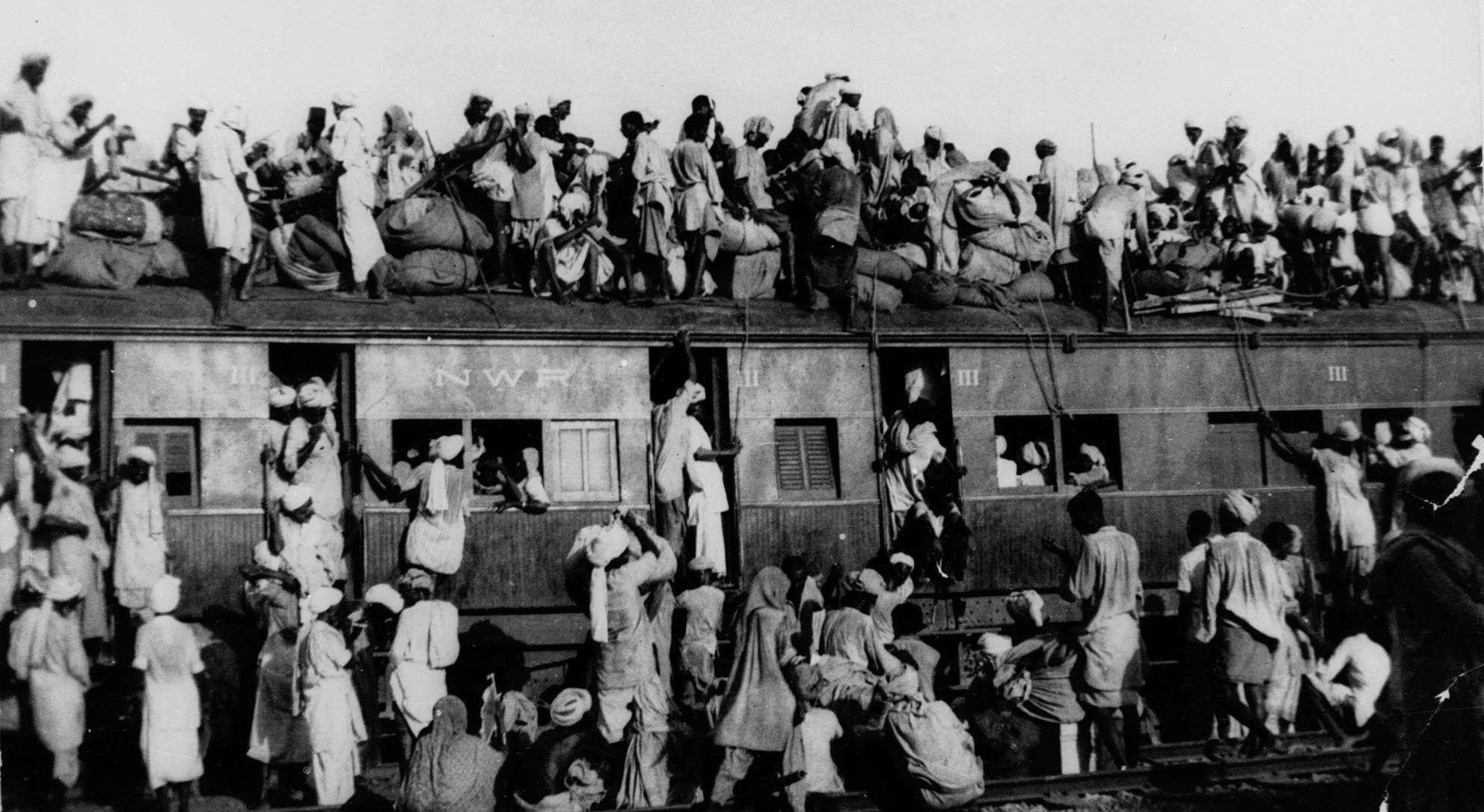

Refugees atop an overcrowded coach of train leaving New Delhi for Pakistan in September 1947. Credit: Wikipedia.

Nehru himself had once said:

“A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.”

If only this ‘new’ world escalated beyond communal violence and hatred.

Today’s Delhi is an amalgamation of migrants, of different religions, cultures, languages and virtues – all painting Delhi in their unique shade. In the gullies of present-day Lajpat Nagar, Amar Colony, Malviya Nagar to Bhogal, Jungpura, Tilak Nagar and Rajouri Garden once resided perplexed migrants, lost in their ‘own land’, suffocating amongst their ‘own people’, haunted by shadow lines.

At times like these, Toba Tek Singh smirks from an unknown place afar, rekindling his desire to find a sense of home, a place to call his own.

As today’s generation watches Manto and fails to grasp the depth and dearth of love in Saadat Hasan Manto’s works, there are some who are struck by a restlessness to seek a part of their own selves in the stories of Partition – from the Sikh man leaving his crops to pursue a different craft in the land of ‘his people’ to the Muslim woman who abandoned her palatial ancestral estate to re-discover herself as a working-class person among ‘her people’.

Also read: My Grandfather’s Bedtime Tale of Tolerance

The narratives echo stories, the legacies of people with beating hearts and welled up eyes – someone’s lover, someone’s landlord, someone’s neighbour.

Someone.

As the decades pass by and the years of psychological catastrophe, political polarity, societal annihilation, economic stagnation and centuries of historical hostility culminate into a friendly cricket match between India and Pakistan, does the youth feel a legacy being passed on to them?

We haven’t had any first-hand experience of the Partition, nor do we have a living substitute. Our understanding of the same has to be attributed to period dramas, hyper-nationalistic movies, and overly-dramatised or romanticised versions of the horror that plagued India for months. The pain, trauma, hopelessness, gore, emotions, separation has, in the very least, been rich bait for creative artists to capitalise on – allowing a part of the Partition to linger on.

‘Division of Hearts’, a 2013 advertisement by Google Search, struck a cord in a hidden, vulnerable place. The joy of reuniting with a loved one separated by such a horrific ordeal felt surreal. As the two young people on each side of the border strive to reunite their respective grandparents, we, as the audience are left to ponder upon the essence of humanity.

Even as accusations today fly thick and fast about the youth being indifferent toward India’s rich history, through initiatives like this, or the penning down of first hand oral narratives, and the simple acts of reading, talking and sharing stories – the past will never die.

As we go about our day, shopping in Lajpat Nagar, taking in the stature of Rashtrapati Bhawan in all its glory at night, crossing the Civil Lines metro station, let’s try to not forget to keep an eye out for the echoes of history that surround us, just waiting to be found.

The Partition may be just a history lesson for some, a remorseful story for others and a historical note for yet others. But there are still many for whom the Partition is still very much a part of them – a living, breathing part of a massacre that will live on for generations to come.

Anandi Sen is an aspiring Journalist, a lover of words, dogs and coffee. She can be usually seen ranting on politics

Featured image credit: Pariplab Chakraborty