If everyone in Hollywood – or any other industry – started renouncing peers for sexual misconduct, how many would be left standing?

Harvey Weinstein. Credit: Reuters/Steve Crisp/Files

“The balance of power is me: 0, Harvey Weinstein: 10,” Lauren O’Connor wrote in a memo several years ago. She was Weinstein’s assistant back then, and the memo was addressed to his company, written in response to his sexual harassment. O’Connor is one of several women who have come forward to accuse Weinstein of sexual harassment and assault in articles published in the New York Times and the New Yorker. Notably and commendably, she is one of the few to speak on the record.

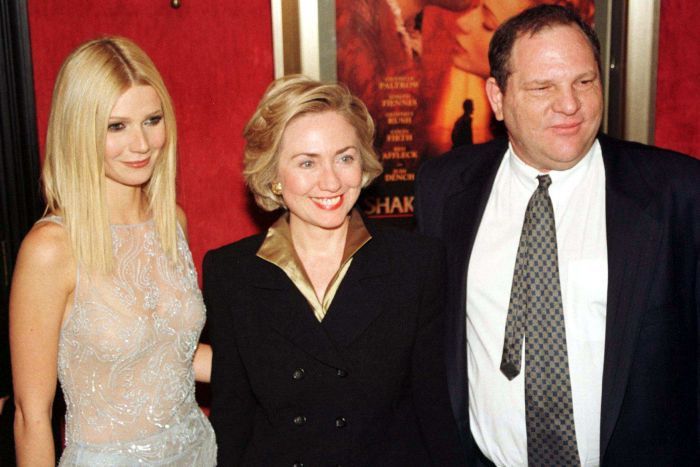

Calling these revelations shocking and eye-opening would be a glib understatement. Weinstein, owner of Miramax and the Weinstein Company, is one of Hollywood’s most “dominant, and domineering” figures. Just those two words go a long way in explaining why an entire industry managed to keep his activities quiet for three decades. The man has been involved in so many Oscar wins that he’s in the top three most-thanked people in Oscar speeches, “just after Steven Spielberg and right before God,” as the New Yorker put it. He has been a prolific supporter and fundraiser for Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. He has been endowed professorships at universities in the names of feminist icons like Gloria Steinem. Weinstein, until this week, was not just a powerful Hollywood executive, but a liberal darling who promoted movies with strong female leads and used his great wealth to further the careers of politicians and spawn academic departments for women’s and gender studies.

But, more importantly, he was – is – a sexual predator. The New York Times and New Yorker collectively cite nearly 20 women who all more or less recount the same sequence of events. Weinstein would invite a woman, usually young and a newcomer to the industry, to his hotel room on the pretext of a professional meeting and the often unassuming, sometimes wary, woman in question would quickly find herself confronted by a naked Weinstein, being persuaded to give him a massage, allow him to massage her or watch him shower or masturbate. And in some cases, like with actor and filmmaker Asia Argento’s, even receive oral sex from him. Can receiving oral sex count as assault? Yes. Any non-consensual sex act counts.

Also read: When ‘No’ is Not ‘No’ in Law

In the coming days, we will continue to talk about Hollywood’s culture of complicity, how to move forward, what to do about Weinstein and his professional legacy. We will also discuss how to reconcile his considerable economic contributions to women’s empowerment with his degradation of women. This story encapsulates so many elements of the problems surrounding sexual harassment and assault that the narrative is already scattering. But the foundational problem we should be discussing is the nature of his sexual assaults.

Most of us have internalised this idea that assault has to look violent. Weinstein did not beat the women he assaulted, he did not even threaten them with physical violence. He did not have to. Sure, part of it is that he’s a big – both large and powerful – guy. But the women didn’t fight back because they knew that rejecting or resisting his advances would effectively end their careers. Lucia Evans, one of the women who spoke to Ronan Farrow at the New Yorker, described an encounter during which Weinstein forced her to perform oral sex on him. She told Farrow that she tried to resist but she thinks she didn’t try “hard enough” because she didn’t want to “kick or fight him”. So instead, she “just sort of gave up. That’s the most horrible part of it, and that’s why he’s been able to do this for so long to so many women: people give up, and then they feel like it’s their fault.”

Shock can make us shut down, overpowering our cognitive abilities until we’re reduced to autopilot mode, allowing someone conniving to take advantage of us. Worse yet, we can find ourselves helpless in the face of the power the other person holds over not only us, but also everyone else we interact with. Our size and physical strength have nothing to do with this.

Louisette Geiss (L) sits with lawyer Gloria Allred as she speaks at a news conference to allege that Harvey Weinstein sexually harassed her, in Los Angeles, California, US October 10, 2017. Credit: Reuters/Lucy Nicholson

One of the most popular reaction articles to follow these revelations gives men advice on how to prevent themselves from mistreating women. The premise is simple: every time you’re faced with an ambiguous situation involving an attractive woman, imagine her as Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson instead, and react to her as you would him. I can appreciate the sentiment – treat women with the same respect that you would men, don’t assume women are attracted to you or want to sleep with you without their explicit say so. The author, Anne Victoria Clarke, is preemptively addressing those men who will now be afraid to mentor women for fear of being accused of inappropriate behaviour. But the article builds on the insidious assumption that men, being physically stronger, are better able to protect themselves in dangerous situations and deserving of a certain respect. It is not always so.

Terry Crews, an actor in the popular TV show Brooklyn Nine-Nine, whose large, buff build is a running trope on the series, came forward on Twitter last night to share his own experience with a predatory Hollywood executive. While attending an event last year, Crews had his crotch grabbed by a male Hollywood executive, in the middle of a crowded room, in front of his wife. He was too shocked, and then in a way too afraid, to react. As a 240-pound black man, he says he knew any physical violence would land him, not the wealthy white executive, in jail instantly.

Sexual assault is not about sex, it’s about power. And it can happen to us whether we identify as a man, woman, transperson or a non-binary individual. And the perpetrator can be anyone. If someone uses their socio-economic status to coerce you into sexual acts or behaviour, no matter how brief, regardless of the number of times it happens or how successful they are in their efforts, it still counts. Unwanted advances in the form of inappropriate comments and late night phone calls also count as sexual harassment.

Like many of the women when they first encountered Weinstein, I too am in my early 20s and trying to carve out a career for myself. It’s not a stretch to say that my superiors’ opinions matter to me. We all have professional idols that we aspire to be like, work with, learn from. Think of the trust we place in people we look up to, letting them shape how we think of ourselves, expanding or contracting our dreams based on their feedback and mentorship. Gwyneth Paltrow, who has come forward with her own Weinstein story in the past day, recounted how shocked she was to find out that the man she thought of as ‘uncle Harvey’ turned out to view her completely differently. Paltrow managed to work with Weinstein in the later years, making it big in Hollywood, and her outspokenness now is unlikely to cost her – she has profitable business ventures of her own now and doesn’t need Weinstein to give her acting roles. Not everyone has been this lucky. And that’s to say nothing of the countless others who remain silent about their experiences with Weinstein or others.

Harvey Weinstein with Gwyneth Paltrow and Hillary Clinton. Credit: Reuters/Peter Morgan

Trust is an invaluable, intangible thing; the kind Mastercard tells you can’t be bought. Signing non-disclosure agreements with Weinstein bought these women some respite and monetary assurance that they were wronged, but the real damage was emotional. Think of the women who gave up working in the movie industry because of Weinstein, those who suffered and continue to suffer from trust and confidence-related issues; others still who have taken such treatment of women as par for the course and navigate all professional interactions like they’re treacherous minefields. So many of us say nothing because we’re afraid of getting caught up in a ‘he said-she said’ battle, we preemptively start to second-guess our own actions and motives, asking ourselves if we could have dressed differently, if we should have said no more, if we didn’t fight back enough. We learn to undermine and invalidate our own selves. New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino summed up the emotional cost of such incidents in two tweets.

& in turn, every bad thing you've ever done, the slightest inconsistency or accommodation, can be made to look the same way: like an excuse

— Jia Tolentino (@jiatolentino) October 10, 2017

Weinstein wielded a jaw-dropping amount of power over Hollywood. He harassed and assaulted women knowing they would have nobody to turn to. His employees and peers were forced into complicity because financial concerns like their own jobs hung in the balance. But by focusing solely on Weinstein, we risk losing sight of the thousands of other predators fostered by the same culture that guarantees impunity to the powerful. Weinstein wasn’t kicked out of his company because of his behaviour. He was sacked because he was caught and put on trial by legacy organisations like the New York Times and the New Yorker, who came armed with testimonies from dozens of women.

It’s the silence of so many other powerful, influential celebrities and Hollywood executives that’s horrifyingly chilling. Most remain silent even now. Others who have spoken out have aimed their condemnation at Weinstein specifically, careful to praise women’s safety while staying mum on other perpetrators. Ben Affleck is a good example. When he tweeted a statement against Weinstein’s actions, he refrained from mentioning his younger brother Casey’s murky history with sexual assault allegations.

Also read: How Bollywood Plays a Role in Normalising Stalking

Roman Polanski and Woody Allen, also infamous for sexual misconduct, continue to be feted by the industry. Notably, none of these allegations have hampered these men’s professional success. They’re all Oscar winners.

If everyone in Hollywood – or any other industry – started renouncing peers for sexual misconduct, how many would be left standing? The fraternity’s silence carries the terrifying possibility that Weinstein is the norm, not the aberration. In which case, his downfall may not be a permanent condition.

And let’s not forget, we only know of these events because journalists found a crack in a wall of silence. Weinstein’s firing is not the conclusive end to misogyny in Hollywood, it’s a siren begging us to pry open other walls of silence.

Nehmat Kaur is a culture writer based in New Delhi. She writes a weekly column for The Wire called Name-Place-Animal-Thing and tweets @nehmatks.