The murder of around 500,000 of Europe’s Roma and Sinti by the Nazis and their collaborators during the second world war is a little-known aspect of the atrocities committed during this period.

In the immediate postwar period, war crimes against Roma were not prosecuted. Survivors struggled to get recognition and compensation for the persecution they experienced. Roma victims were also not acknowledged in monuments commemorating the Nazis’ victims.

Although there is now a greater awareness of the atrocities committed against the Roma, the struggle for recognition continues. The genocide against the Roma is described by Professor Eve Rosenhaft, a historian of modern Germany, as “the forgotten Holocaust”.

As curator of The Wiener Holocaust Library’s current exhibition, Forgotten Victims: The Nazi Genocide of the Roma and Sinti, I aimed to explore this often over-looked history.

The Library is the world’s oldest archive of material on the Nazi era and the Holocaust, and has gathered evidence and information about the experiences of Roma Nazi oppression since the 1950s.

It includes materials collected by academic researcher Donald Kenrick and activist and researcher Grattan Puxon in the late 1960s as part of the first attempt to systematically document the genocide against the Roma.

Forced labour and incarceration

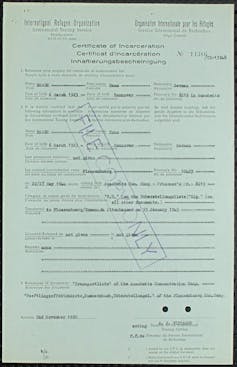

One story featured in the exhibition is that of Hans Braun, a German Sinti man.

Braun survived forced labour service and incarceration in Auschwitz. In the 1980s, he gave a testimony of his experiences, a copy of which is held by the Library.

Other documents in the archive show that Braun’s first attempt to gain compensation failed, probably on the spurious grounds that he was held by the Nazis because he was a criminal, rather than for “racial” reasons.

In the early years following the war, compensation was often denied to Roma and Sinti victims on this basis, despite extensive evidence that they were in fact persecuted as part of a campaign of targeted and ultimately genocidal racism.

Nazi racial ideology

By the late 1930s, Nazi racial ideology had been extended to encompass the notion that, like Jews, Roma were also of “alien blood” and a threat to the racial strength of the “Aryan master race”.

As part of the development of these ideas, Roma were subject to a massive programme of pseudo-scientific investigation.

They were also targeted for forced sterilisation and forced medical experiments.

Margarete Kraus, (in the photograph to the left), a Czech Roma survivor of Auschwitz, was a victim of forced medical experiments.

In this post-war image, taken by German journalist Reimar Gilsenbach in the 1950s, her camp number tattoo is just visible on her left forearm.

The “Gypsy” camp

The exhibition also features eyewitness accounts detailing the so-called “Gypsy” camp in Auschwitz. Julius Hodosi, a Roma man from Burgenland in Austria who survived Auschwitz, recounted his children’s death from starvation in the camp. A number of Jewish survivors, including Hermann Langbein, described witnessing horrific conditions in the “Gypsy” camp. He said:

The conditions were worse than in other camps … the route between the huts was ankle deep in mud and dirt. The gypsies were still using the clothes that they had been given upon arrival … footwear was missing … The latrines were built in such a way that they were practically unusable for the gypsy children. The infirmary was a pathetic sight.

Another witness, Dr Max Benjamin, a Jewish man from Cologne who was a doctor at the “Gypsy” hospital in Auschwitz, gave an account to the Library of the “liquidation” of the “Gypsy” camp in August 1944: “[In] one fell swoop every single one of the gypsies who represented the population of this camp was chased into the gas chambers.”

Of the 23,000 people who passed through the “Gypsy” camp at Auschwitz, 21,000 died – of starvation, ill-health or were murdered in the gas chambers or by other means.

In the 1950s, Hermine Horvath, an Austrian Roma woman, gave the Library an extensive account of her experiences of persecution after the German takeover of Austria in 1938. She was forced into labour service and later survived the camps. She herself experienced sexual violence perpetrated by an SS man, and later witnessed sexual violence committed against Roma girls in Auschwitz by members of the SS.

August (centre), a Sinti boy with relatives in Germany. August died in Auschwitz as almost certainly did the other children in the photograph. Photo: University of Liverpool GLS Add GA, Author provided

But while the Library’s collections on the persecution of and genocide against the Roma contain a great deal of valuable evidence and testimony, it does not tell the entire story. Most of these documents relate to events in Germany, Austria and central Europe, as well as the situation in the camps and ghettos in German-occupied Poland.

But both the Jewish Holocaust and the genocide against the Roma also involved mass shootings carried out by the Nazis and their collaborators in Eastern Europe and in Soviet territories. In other places, such as Croatia, regimes supportive of the Nazis, carried out their own atrocities against the Roma.

The genocide against the Roma and Sinti affected people across Europe from communities in France to those in Ukraine and Greece. Yet this terrible history is frequently overlooked and Europe’s Roma continue to experience extensive discrimination and violence across the continent.

It is hoped this exhibition will help to shine a light on the history of the Roma in Europe, and warn where discrimination and prejudice can lead.

Barbara Warnock, Course Tutor at the Institute of Continuing Education, University of Cambridge

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.