Charlie Chaplin’s sympathy for the working class defines all his most famous silent films.

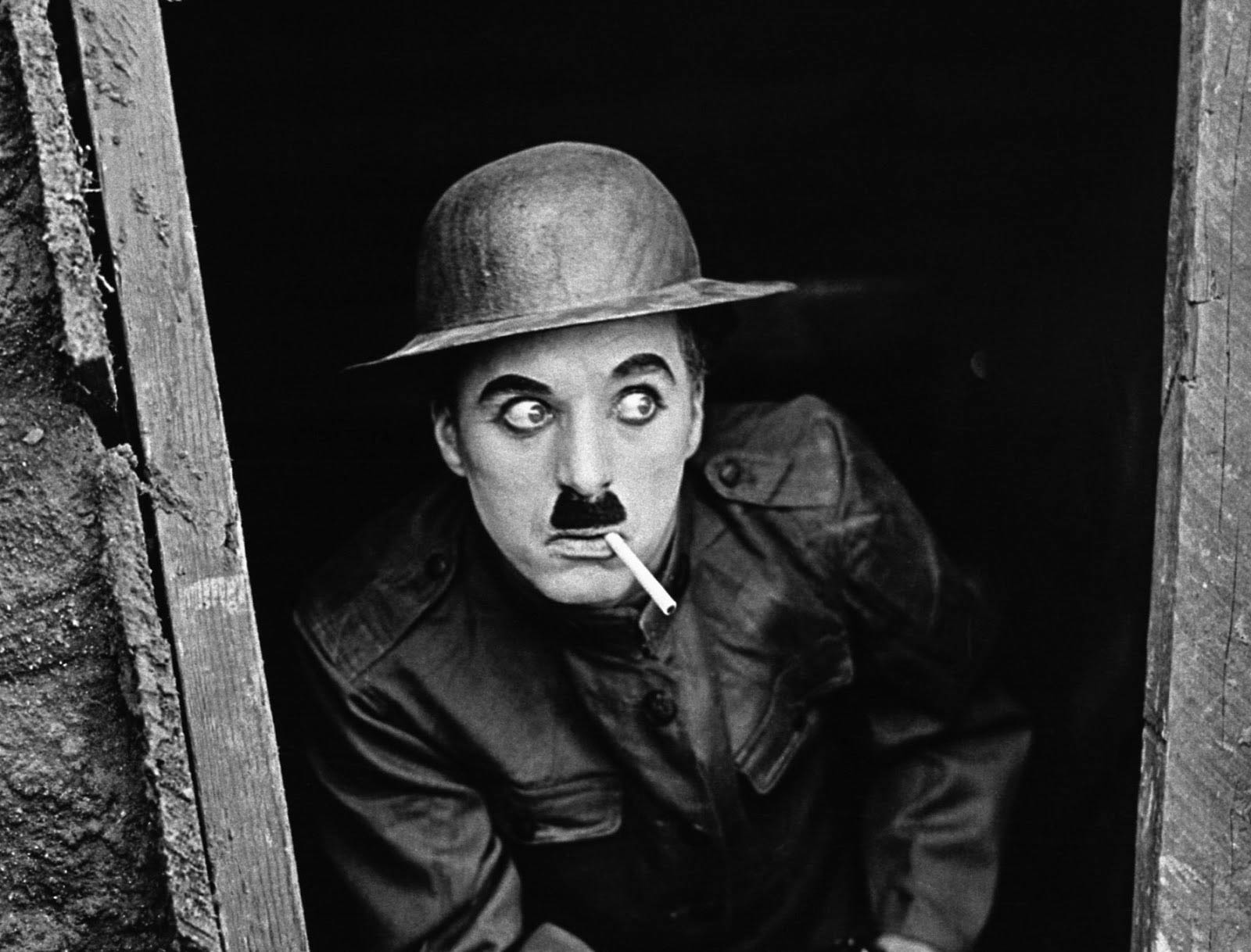

Charlie Chaplin in action.

In September 1952, Charlie Chaplin (1889-1977) looked back at New York on board the Queen Elizabeth. He was bound for Europe, to introduce the continent to his latest film Mousieur Verdoux. On the ship, Chaplin learned that the US government would only let him return to the US – where he had lived for the past three decades – if he subjected himself to an immigration and naturalisation inquiry into his moral and political character. “Goodbye,” Chaplin said from the deck of the ship. He refused to submit to the inquiry. He would not return to the US until 1972, when the Academy of Motion Pictures gave him an Oscar for Lifetime Achievement.

Why did the US government exile Chaplin? The Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) – the country’s political police – investigated Chaplin from 1922 onwards for his alleged ties to the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA). Chaplin’s file – 1,900 pages long – is filled with innuendo and slander, as agents exhausted themselves talking to his co-workers and adversaries to find any hint of communist association. They found none. In December 1949, for instance, the agent in Los Angeles wrote, “No witnesses available to testify affirmatively that Chaplin has been member CP in past, that he is now a member or that he has contributed funds to CP.”

Beside the charge that he was a communist, Chaplin faced the accusation that he was ‘an unsavoury character’ who violated the Mann Act – the White Slave Traffic Act of 1910. Chaplin had paid for the travel of Joan Barry – his girlfriend – across state lines. Chaplin was found not guilt of these charges in 1944. It has subsequently been shown in a number of memoirs and studies that Chaplin was cruel to his many wives (many of them teenagers) and ruthless in his relations with women (Peter Ackroyd’s 2014 book has the details). In 1943, Chaplin married the playwright Eugene O’Neill’s daughter – Oona. She was 18. Chaplin was 54. They would have eight children. Oona Chaplin left the US with her husband and was with him when he died in 1977. There was much about Chaplin’s life that was creepy – particularly the way he preyed on young girls (his second wife – Lita Grey – was 15 when they had an affair and then married; he was then 35). FBI director J. Edgar Hoover had considerable evidence to sift through here, but none of it was found to be sufficient to deport Chaplin.

What was the smoke that got into Hoover’s nose from the fire of Chaplin’s politics? From 1920 onwards, it was clear that Chaplin had sympathies for the Left. That year, Chaplin sat with Buster Keaton – the famous silent film actor – to drink a beer in Keaton’s kitchen in Los Angeles. Chaplin was at the height of his success. With Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford and D.W. Griffith, Chaplin created United Artists, a company that broke with the studio system to give these four actors and directors control over their work. Chaplin was then working on The Kid (1921), one of his finest films and based almost certainly on his childhood. Keaton recounted that Chaplin talked “about something called communism which he just heard about”. “Communism,” Chaplin told him, according to Keaton, “was going to change everything, abolish poverty.” Chaplin banged on the table and said, “What I want is that every child should have enough to eat, shoes on his feet and a roof over his head”. Keaton’s response is casually insincere, “But Charlie, do you know anyone who doesn’t want that?”

Chaplin came to the US just after the Russian Revolution. He saw the growing lines of unemployment and distress in the US – an unemployed population that grew from 950,000 (1919) to five million (1921). This was a time of great class struggle – the Palmer Raids conducted by the government against the communists, on the one side, and the general strike in Seattle as well as the Battle of Blair Mountain by the mineworkers of Logan County, West Virginia, on the other side.

Chaplin’s silent films were anchored by the figure of the Tramp, the iconic poor man in a modern capitalist society. “I am like a man who is ever haunted by a spirit, the spirit of poverty, the spirit of privation,” Chaplin said. That is precisely what one sees in his films – from The Tramp (1915) to Modern Times (1936). “The whole point of the Little Fellow,” Chaplin said in 1925 of the tramp figure, “is that no matter how down on his ass he is, no matter how well the jackals succeed in tearing him apart, he’s still a man of dignity.” The working class, the working poor, are people of great resourcefulness and dignity – not beaten down, not to be mocked. Chaplin’s sympathy for the working class defines all his most famous silent films.

It was Chaplin’s popularity and his message that disturbed the FBI. “There are men and women in far corners of the world who never have heard of Jesus Christ; yet they know and love Charlie Chaplin,” noted an article that an FBI agent clipped and highlighted in Chaplin’s file. Chaplin’s plainly-depicted criticism of capitalism did not fail to impress the world’s peoples nor disturb the FBI. “I don’t want the old rugged individualism,” Chaplin said in November 1942, “rugged for the few and ragged for the many.”

The great limitation in his films is the depiction of women. They are always damsels in distress or rich women who are desired by poor men. There are few ‘women of dignity’, women who – at that time – were in pitched battles for their own rights. In fact, many silent films in both the UK and the US disparaged the Suffragette movement of their time – from A Day in the Life of a Suffragette (1908) to A Busy Day (1914, which was originally titled A Militant Suffragette). In this latter film, only six minutes long, Chaplin plays a suffragette who is boorish and then dies by drowning.

The film was released the same year as Sylvia Pankhurst (1882-1960) founded the East London Federation of Suffragettes to unite suffragette politics with socialism. Pankhurst, unlike Chaplin, would join the Communist Party and – in 1920 – would author A Constitution for British Soviets. She would leave the Communist Party, but remained a devoted communist and anti-fascist for the rest of her life. If only Chaplin’s sexism had not blocked him from celebrating his contemporaries such as Pankhurst, Joan Beauchamp (another Suffragette and founder of the British Communist Party) as well as her sister Kay Beauchamp (co-founder of The Daily Worker, now Morning Star) and Fanny Deakin.

What drew Chaplin directly into the orbit of institutional left-wing politics was the rise of fascism. He was greatly troubled by the Nazi sweep across Europe. Chaplin’s film The Great Dictator (1940) was his satire of fascism – a film that should be watched by all in our times.

Two years after that film was out, Chaplin flew to New York City to be the main speaker at a Communist-backed Artists Front to Win the War event. Chaplin took the stage at Carnegie Hall on 16 October 1942, addressed the crowd as ‘comrades’ and said that Communists are “ordinary people like ourselves who love beauty, who love life”. Then, Chaplin offered his clearest statement on communism – “They say communism may spread out all over the world. And I say – so what?” (Daily Worker, October 19, 1942). In December 1942, Chaplin said, “I am not a Communist, but I am proud to say that I feel pretty pro-Communist”.

Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator.

Chaplin was impressed by the principled and unyielding stand taken by the communists against fascism – whether during the Spanish Civil War or in the Eastern Front against the Nazi invasion of the USSR. In 1943, Chaplin called the USSR “a brave new world” that gave “hope and aspiration to the common man”. He hoped that the USSR would “grow more glorious year by year. Now that the agony of birth is at an end, may the beauty of its growth endure forever”. When asked a decade later why he was so vocal about his support for the USSR – including with appearances at the communist fronts such as the National Council for American-Soviet Friendship and the Russian War Relief – Chaplin said, “during the war I sympathised much with Russia because I believe that she was holding the front”. This sympathy remained through the remainder of his life.

Chaplin had not calculated the toxicity of the Cold War era in the US. In 1947, he told reporters, “These days if you step off the curb with your left foot, they accuse you being a communist”. Chaplin did not back off from his beliefs or betrayed his friends. At that same press conference he was asked if he knew the Austrian musician Hanns Eisler, who was a communist and who wrote the music for many of Bertolt Brecht’s plays. He had fled Nazi Germany for the US to work in Hollywood. Eisler had composed songs for the Communist Party (he would write music for the anthem of the German Democratic Republic – Auferstanden Aus Ruinen). Chaplin came to his defence. When asked about his association with Eisler at that 1947 press conference, Chaplin said that Eisler “is a personal friend and I am proud of the fact…I don’t know whether he is a communist or not. I know he is a fine artist and a great musician and a very sympathetic friend”. When asked directly if it would make any difference to Chaplin if Eisler was a communist, he said, “No it wouldn’t”. It took a lot of courage to defend Eisler, who would be deported from the US a few months later.

When Chaplin died in Switzerland in December 1977, he was mourned far and wide. In Calcutta, where a Left Front government had only just come to power in a landslide in June, artists and political activists gathered the next day to mourn him. The main speaker at the memorial service was the Bengali film director Mrinal Sen. In 1953, Sen had written a book on Chaplin – illustrated by Satyajit Ray.

Neither Sen nor Ray had made any of their iconic films as yet (both released their first films in 1955, Ray’s Pather Panchali and Sen’s Raat Bhore). “Without a moral justification,” Sen said at the memorial meeting, “cinema is ridiculous, is atrocious, is an outrage. It is a social activity. It is man’s creation.” The gap between art and politics should not be too wide, Sen warned. He was thinking of Chaplin’s films, but also of his own. At that time, Sen was working on Ek Din Pratidin (One Day, Everyday), a superb film that chronicles the possibilities of women’s emancipation. Here Sen went far beyond Chaplin. His communism included women.

Vijay Prashad is the author of The Death of the Nation and the Future of the Arab Revolution from LeftWord Books.