Considered by many to be the best television drama series ever, The Wire ran from June 2, 2002, to March 9, 2008. Made and set in Baltimore, it employed a large ensemble cast playing cops, junkies, dealers, lawyers, judges, dockers, prostitutes, prisoners, teachers, students, politicians, and journalists. The dramatis personae ranged widely, not only horizontally but vertically, from the foot soldiers of the drug trade, police department, school system, and newspapers through middle management to the higher executives, showing parallel problems and choices pervading the whole society.

But summing up its plot does not tell the full story. As the series progressed, The Wire’s individual stories opened out into an analysis of an overarching, and at times irresistible, system shaping each aspect of society. The series demonstrated the potential of television narrative to dramatise the nature of the social order, a potential that TV drama has long neglected or inadequately pursued.

Each season ended with a stirring montage that pulls together the various plots and projects them into the immediate future, leaving the viewer pondering the story lines’ outcomes and reflecting on their causes and consequences. And off-screen, The Wire’s writers provided a rich context to its intentions and message, a meta-narrative that situates the series within twenty-first-century American capitalism. In many ways, The Wire is a Marxist’s idea of what TV drama should be — stylish and intellectually serious, a series with compelling plotlines woven through a rigorous analysis of society.

We’re not as smart as The Wire

The Wire’s creator David Simon admitted “the raw material of our plotting seems to be the same stuff of so many other police procedurals.” And The Wire certainly emerged into an evolving genre, one in which dissonance, disruption, and ambiguity of resolution had increased over decades. The gap between law and justice widened in TV drama as it has widened in social consciousness. By the early 2000s cops such as Andy Sipowicz (NYPD Blue), Frank Pembleton (Homicide: Life on the Street), Vic Mackey (The Shield), and Olivia Benson (Law & Order: Special Victims Unit) were a different species from Joe Friday of 1950s Dragnet. They were no longer untainted and uncomplicated agents of righteousness, but morally conflicted, psychologically complex characters struggling with difficult personal lives as well as a crumbling social contract. They crossed lines, both ethically and legally.

Nevertheless The Wire represented a leap in the evolution of the genre. It moved complexity up a level, particularly in terms of social context, showing a social order in steep decline. It also broke from the standard narrative structure to which most cop shows still adhere. In these, a relatively harmonious status quo is disturbed by a murder, rape, or assault, followed by an investigation combining elements of pavement pounding, interrogation, and forensic detection. The script brings the assailant to justice by the final scene and restores harmony. The Wire’s narrative structure unfolds according to a much longer and less predictable story arc, which reveals a more astute social analysis. As Simon observed:

On shows where the arrest matters… the suspect exists to exalt the good guys, to make the Sipowiczs and the Pembletons and the Joe Fridays that much more moral, that much more righteous, that much more intellectualised. It’s to validate their point of view and the point of view of society. So, you end up with same stilted picture of the underclass. Either they’re the salt of earth looking for a break and not at all responsible, or they’re venal and evil and need to be punished.

The Wire also takes aim at the seemingly omnipotent and omniscient CSI-type police procedurals. In these shows, the labor of detection is effectively reduced to a glamorised pseudoscience pursued by investigators dressed like fashion models and working in crime labs that look like night clubs. In contrast, an early episode of The Wire shows detectives waiting at a crime scene for forensic investigators, who are tied up with the theft of a city councilman’s lawn furniture, while the corpse is decaying. On another occasion, the evidence for multiple murders is inappropriately amalgamated because a temp has failed to understand the meaning of “et al.” Most consequentially, in season five, Detective Jimmy McNulty contrives a serial killer scenario through manipulation of forensic evidence (after discovering that postmortem bruising can be mistaken for strangulation) in a convoluted scheme to get funding for real police work. The crime lab itself is down at the heel, and its personnel look like ordinary working people dressed for a day’s work rather than a catwalk.

An anecdote told by actor Andre Royo (Bubbles), recounting his experience on Law and Order, highlights the gulf between The Wire and more conventional cop shows:

In one scene, the cops come to my house because someone is killed and I have the weapon there. While we were shooting, I saw an open hallway and I ran out. And the director yelled “Cut” and said, “We’re not as smart as The Wire. On our show, you put your hands up and get handcuffed.”

The Sopranos offers another point of comparison, as an HBO production that also took crime drama into new territory and moral ambiguity to a new level. In speaking of The Sopranos, David Simon has praised this aspect of the show and said that he himself is not interested in good and evil. However, despite what he says, the series itself as well as his other utterances in interviews belie this. While The Wire casts virtually every character in a stance of moral compromise and shows sympathy for criminals, it nevertheless has a strong moral compass and does not seduce its audience into moral dissolution as The Sopranos arguably does. The Wire constantly raises the question of a moral code, even if along unconventional lines, and challenges its audience to moral reflection.

Our current condition

Breaking from genre norms on many levels, The Wire went beyond even the best of previous police procedurals. It set out to create something more panoramic and more provocative, or, as Simon himself said, “storytelling that speaks to our current condition, that grapples with the basic realities and contradictions of our immediate world,” that presents a social and political argument. It is a drama about politics, sociology, and macroeconomics.

He described how the story line unfolds in the space “wedged between two competing American myths.” The first is the free-market, rags-to-riches success story that says “if you are smarter… if you are shrewd or frugal or visionary, if you build a better mousetrap, you will succeed beyond your wildest imagination.” The second is the American idea that “if you are not smarter… clever or visionary, if you never do build a better mousetrap… if you are neither slick nor cunning, yet willing to get up every day and work your ass off… you have a place. And you will not be betrayed.”

According to Simon, it is “no longer possible even to remain polite on this subject. It is… a lie.” The un-packaging of this new reality across the series reveals much about America’s economic and existential crisis. Much TV drama shows the slippage in the grip of these myths while still remaining in thrall to them. The Wire broke more decisively as it explored the social crisis resulting from a world in which many people will not succeed or necessarily even survive, whether they are smart or honest or hardworking; indeed even conceding that they might even be doomed because they are.

Nick Sobotka (Pablo Schreiber) stares through the fence at the Baltimore docks in season two.

Rarely, if ever, has a television drama constructed a narrative with such a strong thrust toward meta-narrative. The Wire’s intricate and interwoven story lines dramatise the interaction between individual aspirations and institutional dynamics. These build into the larger story of a city, not only the story of Baltimore in its particularity, but with a metaphoric drive toward the story of Every City. Each character and story line pulses with symbolic resonance about the nature of contemporary capitalism. While the text itself does not name the system, the meta-text does with extraordinary clarity and force.

David Simon, the primary voice of this collective creation, has engaged in a powerfully polemical discourse articulating the worldview that underlies the drama. The meta-narrative, the story about the story, is implicit within the drama, but explicit in the discourse surrounding the drama, going way beyond that of any previous TV drama.

Shakespearean is a term often used to describe what is perceived as quality drama, and it has often been used to describe The Wire. Simon was, however, quick to correct his interviewers with regard to its dramatic provenance:

The Wire is a Greek tragedy in which the postmodern institutions are the Olympian forces. It’s the police department, or the drug economy, or the political structures, or the school administration, or the macroeconomic forces that are throwing the lightning bolts and hitting people in the ass for no decent reason.

This larger theme recurs across numerous interviews: The Wire is not a drama about individuals rising above institutions to triumph and achieve redemption and catharsis. It is a drama where those institutions thwart the ambitions and aspirations of those they purportedly exist to serve; one where individuals with hubris enough to challenge this dynamic invariably become mocked, marginalised, or crushed by forces indifferent to their efforts or to their fates; where truth and justice are often defeated as deceit and injustice are rewarded.

Of all the forces in motion — in politics, education, law, and media — most crucial are the macroeconomic ones, which underpin and determine the operation of the other institutions. For David Simon, “[c]apitalism is the ultimate god in The Wire. Capitalism is Zeus.” The worldview underlying ancient Greek tragedy is one in which individuals do not control the world. They are at the mercy of forces beyond their control. The Wire is a drama of fated protagonists, a rigged game, where there is no happy-ever-after ending.

Literary references abound in the discourse surrounding the series. Explaining why he thinks it to be the best in the history of television, Jacob Weisberg argued:

No other program has ever done anything remotely like what this one does, namely to portray the social, political, and economic life of an American city with the scope, observational precision, and moral vision of great literature… The drama repeatedly cuts from the top of Baltimore’s social structure to its bottom, from political fund-raisers in the white suburbs to the subterranean squat of a homeless junkie… The Wire’s political science is as brilliant as its sociology. It leaves The West Wing, and everything else television has tried to do on this subject, in the dust.

The blog Scandalum Magnatum posted an entry on Simon entitled “Balzac of Baltimore,” arguing that Balzac, Marx’s favourite novelist, sought to portray society in all its aspects, showing how it was falling apart at the hands of the rising bourgeoisie. As Engels observed of Balzac, although his sympathies were with the class doomed to extinction, there was more to be learned from his fiction than from all the professed historians, economists, and statisticians of the period together. In building a whole world, The Wire rivals the breadth of vision of the nineteenth-century realist masterworks. It too anchors its sympathies in a class doomed to extinction, living in Simon’s shadows of the “brown fields and rotting piers and rusting factories,” “dead-ended at some strip mall cash register,” or “shrugged aside by the vagaries of unrestrained capitalism.”

The other America

Significantly, The Wire’s writers were novelists and journalists who lived in close proximity to the experience of “the other America” they sought to uncover. “None of us are from Hollywood,” Simon wrote. “[S]oundstages and backlots and studio commissaries are not our natural habitat.” In his opinion:

So much of what comes out of Hollywood is horseshit. Because these people live in West L.A., they don’t even go to East L.A…. [W]hat they increasingly know about the world is what they see on other TV shows about cops or crime or poverty. The American entertainment industry gets poverty so relentlessly wrong… Poor people are either the salt of the earth, and they’re there to exalt us with their homespun wisdom and their sheer grit and determination to rise up, or they are people to be beaten up in an interrogation room by Sipowicz.

The writers took credibility seriously. This meant, according to Ed Burns, “You’ve got to know the world… otherwise it’s medical crap here and cop crap there and a love story,” a series by the numbers. For senior editor Eric Ducker, it was important to reflect the world as it is, so The Wire he said “is not some sort of proletariat revolution where longshoremen and drug dealers have seized the means of storytelling, but it’s as close as you get to an East Coast, rust belt, post-industrial city telling its own story.”

“Stringer” Bell (Idris Elba) in the courtroom of D’Angelo Barksdale’s murder trial in season one.

Despite their distance from the dominant television industry, the writers learned the craft of TV drama production impressively. Everything — from the writing to the shooting — is honed to the purpose of showing the world. Even the directorial practice of staying wide in terms of visual composition is shaped with this intent. Image construction often shows lives constricted by confining spaces, which are then depicted in relation to the larger environment surrounding them.

We see characters and events against the backdrop of the city from its grandest views: from executive offices or luxury condos overlooking the harbor. And we also see the windowless basement offices where police monitor wiretaps and the grim abandoned houses where addicts inject heroin. The beauty and space open to some sections of the population always stand in sharp contrast to the ugliness and claustrophobia circumscribing the others. One group cannot exist without the other.

The Wire is “about untethered capitalism run amok, about how power and money actually route themselves in a postmodern American city, and ultimately, about why we as an urban people are no longer able to solve our problems or heal our wounds.” It is a show in which the excesses of capitalism are not reduced to the actions of a few proverbial bad apples. As Scandalum Magnatum argued:

Most “progressive” Americans think in terms of “corporations” rather than “capital.” The former has people in charge who are evil; the latter is a faceless and diffuse social force, which controls simply by going about its business in a banal and unthinking manner. In not giving capital a face, Simon removes the easy way out.

Nevertheless, capitalism is largely invisible within The Wire. There is a sense in which, like the Greek in season two, it hides in plain sight. The character of the Greek sits in the foreground, silent and unacknowledged, at a café counter while underlings conduct business on his behalf. To David Simon, the Greek “represented capitalism in its purest form.” He only becomes a visible actor when his interests are directly threatened. He reappears briefly in the final montage of season five, still sitting in the café, still present, still barely observed.

Narco-capitalism is shown as the only viable “economic engine” in neighbourhoods where no other path to wealth exists. Those excluded from making a living through the dominant system create their own alternative. For Simon and Burns, drug culture provides “a wealth-generating structure so elemental and enduring that it can legitimately be called a social compact.”

An unskilled and poorly educated underclass is trapped between the drug economy and the war on drugs. The Wire compresses decades of the Baltimore drug trade into its five seasons. It uses the industry to tell a story about capitalism, contrasting its “legitimate” modes of accumulation with “illegitimate” ones. When McNulty observes, “everything else in this country gets sold without people shooting each other behind it,” the irony is implicit. Within legitimate capitalism, the economic system’s violence remains largely hidden. Only in the primitive accumulation of the drug economy is violence visible.

Even within this process, as the scripts develop it, the characters with more power have an impetus to launder the money, to bring greater order, and to reduce the overt violence, all the more effectively to accumulate further. For example, a character is developed who provides enormous assistance in this regularising aspect of capital. He is lawyer Maurice Levy, who defends drug dealers in court, procures their political connections, and facilitates their property transactions.

A key figure in the trajectory of transformation from primitive to more advanced accumulation is Russell “Stringer” Bell, second-in-command of the Barksdale drug organisation. When McNulty tails him, the detective finds that Bell’s destination is Baltimore City Community College, where the drug lord is taking a course on macroeconomics. As Bell progresses in his course and tightens his control of the organisation, we see him explicitly applying his lessons to the drug trade. From the start, Bell conceptualises the process of his group’s capital accumulation at a level inaccessible to street dealers: “Every market-based business runs in cycles. We’re in a down cycle now.”

Indeed, under Bell’s leadership, we see the organisation progress from making on-the-fly decisions in the grubby back room of a strip club to holding formal meetings in a funeral home according to Robert’s Rules of Order to forming a cartel that meets in an upmarket hotel conference facility laid out as a corporate boardroom. He comes to recognise that the traditional goal of controlling territory is meaningless if the group distributes bad product. Moreover, it’s the fight for territory that brings the bodies, and the bodies that bring the police, which forces dealers off the streets, affecting productivity and profits. Eventually Bell uses illegal profits to buy legal property. He strives to mix with the movers and shakers of the propertied class, bribe politicians, accumulate further capital, and integrate into the dominant system. When police enter his upscale apartment, the camera settles on a book McNulty pulls down from the shelf: Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations.

Ultimately however, Stringer Bell is felled by hubris. Despite or perhaps because of his education, he fails to see the true nature of the system that confronts him. Bell takes his lessons in economics at face value. Consequently he is conned out of millions of dollars by the corrupt state senator, R. Clayton “Clay” Davis. Simultaneously, he is betrayed by his own group’s ostensible leader, Avon Barksdale, recently released from prison and unimpressed by Bell’s more businesslike attempts to reform the drug trade. Avon stands for a more traditional criminal subculture. He poses as a community leader, serving food at a cookout and financing a boxing club; in the end he betrays Bell for reasons of family loyalty.

Ironically, it is Marlo Stanfield, successor to the Barksdale organisation, who reaps the rewards of Stringer Bell’s business education. Marlo takes the best of both worlds: he understands that bodies bring the police, but rather than eradicate the violence, he hides the bodies, rendering the violence invisible. In the end, Marlo achieves everything that Stringer wanted, but has no idea of where to go with it. He meets with the city powers at a reception in a high-rise office block, looking out across the city that they each in their different ways control. For all of his frequent callousness, Stringer believed he could tame the system. Marlo stands on the verge of admission to the inner circle, his extreme ruthlessness seemingly marking him out as one of its own.

Juking the stats

The political structure, as portrayed in The Wire, has adopted the priorities of finance capitalism. Commodity value is consistently prioritised over use value. The public sector has become impoverished — to the point where it cannot meet basic needs — while money accumulates in other sectors, particularly in the drug trade, beyond any possible need or use. Marlo, for example, has no idea what to do with all the wealth he has amassed. Meanwhile, politicians cut budgets, and police and teachers cut corners on the job and go into debt at home.

To defend their declining position, educational and legal institutions adopt prevailing modes of justification so that public services appear to produce little in the way of real results. The school system struggles but fails to educate, and the police force strives but fails to reduce crime. This environment seems to produce nothing of market value, so how is performance in the social sector to be measured? Paradoxically, the measurement that exists cloaks the lack of meaningful performance. Even further, producing the metrics disincentivises meaningful performance. The street rips drain time and energy from policing, which should be targeting the powerful players and the causes of crime. Teaching to the test does the same with respect to education, which should be opening the mind to the world.

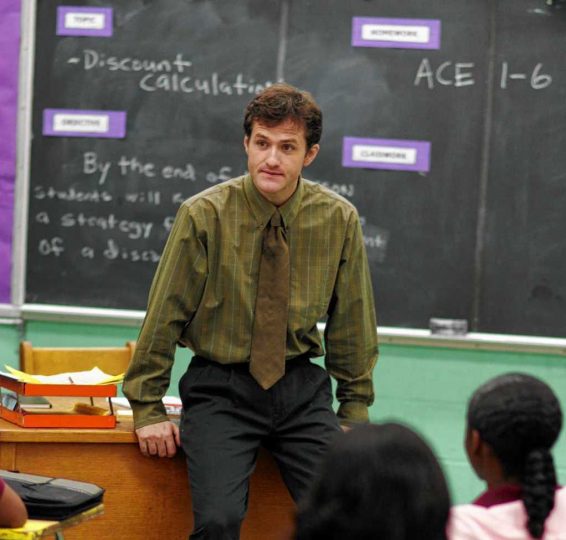

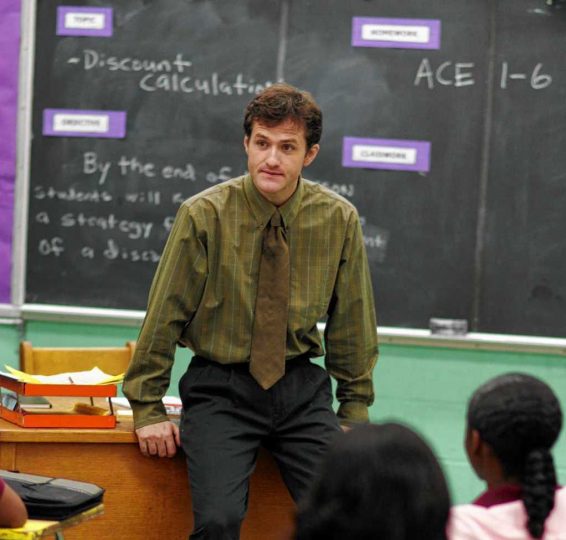

Roland Pryzbylewski (Jim True-Frost) in the classroom in season four.

From the first episode, this kind of dilemma is made starkly clear. McNulty, after talking to a judge, unwittingly brings to the bosses’ attention a series of related murders linked to the Barksdales. The detective is reprimanded in the harshest terms for violating the chain of command. However, what most disturbs the head of the homicide division, Major William Rawls, is the fact that McNulty uses as evidence one of the murders from the previous year, which would therefore have no bearing on the current year’s case-solved statistics.

This massaging of crime figures is clearly illustrated and referred to as “juking the stats.” In season three we are introduced to COMSTAT meetings. Via Powerpoint slides, police give figures to suggest there are now decreases in crime. Since police at all levels, from the commissioner down, are often berated and even demoted for their failures, they defend themselves by finding ways to reclassify crimes, making aggravated assaults into common assaults. Sometimes they even make bodies disappear. When the bodies concealed by the Stanfield gang are discovered, the homicide sergeant suggests to the detective that he might want to leave them where they are, as there are only three weeks left in the year and the unit clearance rate is already under 50%.

Other relevant metrics play a role, as well as the year and body count. For example, some dead bodies are discovered in a location with an unimportant zip code — a story line with strong undercurrents of race and class. As the cops put it, dozens of black, poor bodies in Baltimore count for less than one white suburban ex-cheerleader in Aruba. Such a conversation takes place in the local newsroom as well. In other instances, overtime pay can become a metric, as one lazy detective insists that “cases go from red to black via green.”

The tyranny of numbers extends beyond the police department. When Roland Pryzbylewski is dismissed from the police force for accidentally shooting a black officer, he becomes a public school teacher. Sitting in a meeting to discuss how to “teach the test” for the forthcoming No Child Left Behind standardised tests, he experiences a flash of recognition. “Juking the stats,” he comments to a colleague, “you juke the stats and majors become colonels. I’ve been here before.”

Manipulating teaching procedures just to achieve adequate test scores parallels manipulating crime statistics at COMSTAT. The progress made by Pryzbylewski’s own unconventional teaching methods, and by an experimental program designed to resocialise troubled children, is eviscerated. In a succession of scenes ironically juxtaposed against each other, the high school’s seminar on a teaching strategy for the test is edited against a police meeting on anti-terrorism.

The police are the most sustained presence in the series. Characters such as McNulty, Lester Freamon, Cedric Daniels, and Kima Greggs have a commitment to building strong but difficult cases, tracing how the money and power are routed. However, these officers are constantly under pressure from those higher up the chain of command, who are in turn under pressure from city hall, to produce easy street rips that will produce arrests and drug seizures. That’s the kind of police action known to generate enthusiastic press conferences and impressive crime stats. Under such pressure, Daniels worries that one generation is training the next how not to do the job.

The good guys do not win. By the end of the series some of the best police must go — Daniels, McNulty, Freamon, Howard “Bunny” Colvin — while the worst thrive — Rawls, Stan Valchek, Ervin Burrell. Yet some — Greggs, Bunk Moreland, Ellis Carver — also survive and try to do another decent day’s work. The police exhibit the same moral ambiguity as does society as a whole. The venal but eloquent Sergeant Jay Landsman reflects, “We are policing a culture of moral decline.”

A dark corner of the American Experiment

Some of the scenes where we see most clearly the identity, contradictions, and solidarity of the police subculture and its relation to wider society are at the wakes for dead policemen. The ritual usually involves going to an Irish bar, laying out the corpse on a pool table, drinking whiskey, singing “The Body of an American” (The Pogues), and eulogising the dead cop. Discussing the dead policeman at Cole’s wake, one of the most memorable scenes in the series, Homicide Sergeant Landsman characterises the characters’ lives as “sharing a dark corner of the American experiment.”

In a montage of brief shots, the character of Cole, the Irish cop, is visually reconstructed. Some of the elements in the mise-en-scène are contradictory, even outlandish. On a pool table draped with a police flag are arranged a photo of the dead officer in dress uniform, rosary beads hanging over one corner, and a St Brigid’s cross lying in front of it. A shot of a bottle of Jameson Irish Whiskey held in the corpse’s left hand cuts quickly to a close-up of the wedding ring on his third finger. Shots of cuff links, cigars, and a tie follow in quick succession before settling briefly on his police shield. The figure of Cole as a symbol of policing, albeit a chaotic and contradictory one, is thus established, a perception heightened by Landsman’s observation that he was neither the world’s greatest cop nor its worst.

The incongruity of these elements is replicated even more forcefully at the seeming wake held for McNulty when he leaves the police force. He is symbolically dead, having left the brotherhood. Ironically for this uniquely promiscuous and self-destructive detective, the table is positively cluttered with religious kitsch, including votive candles and plaster hands draped with a rosary, alongside the obligatory bottle of Jameson and statue of the Virgin Mary. The verbose and articulate Landsman is momentarily lost for words, but he must ultimately admit to a grudging respect for the “dead” detective, the black sheep. In the only positive words he ever spoke to or about McNulty, Landsman declares that if his own body were found lying dead on the street, there is no one he would rather have standing over him investigating the case than McNulty.

Season five takes as its theme the mass media. Journalists, too, find themselves inhabiting a dark corner of the American experiment. Beset by pressures of bylines, deadlines, and prizes alongside problems created by cutbacks, out-of-town ownership, buyouts of the most experienced staff, and declining circulation, reporters find themselves disconnected from the city they are charged to report. Some go for the fast track to promotion and prizes, undercutting the process of building long-term knowledge of long-term situations, establishing contacts, creating trust, and understanding more of the context in which they operate.

The Baltimore Sun newsroom in season five.

Simon believes that the indifferent logic of Wall Street has poisoned relations between newspapers and their cities. The management of the Baltimore Sun, as represented in the series, is preoccupied with gaining Pulitzer Prizes. The newspaper’s formula, according to Simon, is to “surround a simple outrage, overreport it, claim credit for breaking it, make sure you find a villain, then claim you effected change as a result of your coverage.” Much journalism focuses on the symptoms rather than the disease, which Simon compared to coming to a house hit by a hurricane and making voluminous notes on the displaced roof tiles. One type of story is “small, self-contained and has good guys and bad guys,” whereas the other is informed by a bigger picture and a longer history and reveals what is happening in society.

In the newspaper plotline, the conflict is not just about the stories that the reporters get wrong for one reason or another, but about the fact that they fail to get at all the major stories that dominate the drama, things which the viewers but not the reporters understand. That, according to Simon, is the “big-ass elephant in our mythical newsroom.” The reporters do not uncover the stories about juking the stats on crime or education. They do not reveal that this is being driven by city hall or that the mayor is reverting to the practices he pledged to reform. They do not probe the connections between property transactions and political corruption. They have no idea of how the drug trade works. The death of Proposition Joe, a major player in East Baltimore drugs, is relegated to the inside pages, and the death of Omar, a semi-mythic figure in West Baltimore, is bumped from the paper altogether.

In depicting the world of print journalism, the script provides a strong sense of social decline, driven by Simon’s own experience of reporting for the Baltimore Sun and then following its transformation over the past few decades. In one scene, two journalists remember why they wanted to be newspapermen. One recalls seeing his father read the paper every morning at breakfast so thoroughly and intently that the child wanted to be part of something so important as to require that sort of concentrated attention. Another told of a man whom he saw on the bus every day and how that man folded his paper in sections and read it with such great care. There is a sense of a loss of coherence in a society where the daily newspaper was once part of a wider workaday ritual.

All the pieces matter

Another absence, also evoking a sense of social decline, is political protest. We see little organised opposition to the deindustrialisation and demoralisation of the city or to the macroeconomic forces driving its decline. This is worthy of remark, since the writers of The Wire wanted to make a companion series titled The Hall that would have focused more specifically on the political system. According to Simon, it would have acted as “an antidote to the Father-Knows-Best tonality of more popular political drama.”

The protests we do see are effectively stunts, stage managed from the top. On one occasion, new mayor Tommy Carcetti is seeking to divert attention from the failings of the law enforcement and education systems. He exploits a growing sense of outrage surrounding an apparent spate of homeless murders by organizing a candlelight vigil outside city hall. Using this masterful piece of politicking, he can place the blame for homelessness on federal and state administrations, both Republican, as opposed to the Democratic city administration.

On another occasion, when Clay Davis, a corrupt state senator, goes on trial, he manages to transform the accusation of gross corruption to self-defense against a racist witch hunt. He presents himself as a beneficent patron of the city’s black poor, his pockets never full for long, as he hears his constituents’ troubles and pays their bills. He arrives at the courthouse carrying a copy of Aeschylus’s Prometheus Bound, the tale of “a simple man, who was horrifically punished by the powers that be for the terrible crime of trying to bring light to the common people.”

In the courtroom, drawing on the rhetoric of the Civil Rights Movement, Davis skillfully manipulates the discourses of race and class against his opponents, who, he claims, have no idea how things are for the black poor. He refers to those pulling the strings above the black state attorney. He enlists a corrupt former mayor to his cause, who makes reference to those “persecuting… our leaders.” This courthouse rally culminates in a chorus of “We Shall Not Be Moved.” While it is apparent that significant sections of The Wire’s black political establishment are engaged in graft, the enduring and systemic character of inequality enables them to draw on a radical tradition and to distort it to nefarious ends.

The spirit of the ’60s finds such echoes elsewhere in The Wire. Avon Barksdale and Stringer Bell regularly use the black power handshake. In one conversation Avon refers teasingly to their youthful enthusiasm for “that black pride bullshit.” Brother Mouzone, an enforcer brought from New York to Baltimore by the Barksdales, is a ruthless gun for hire, whose appearance evokes Malcolm X, but he is without substance. He prides himself on reading the Nation, the New Republic, the Atlantic Monthly, and Harper’s, but how he relates the political debates in them to his role as enforcer in the drug trade is unclear. A philosophy of collective liberation has morphed into a Hobbesian war of all against all. For all their talk of being brothers, Avon and Stringer have already betrayed each other, and Avon has set in motion the murder of Stringer.

This tradition of black radicalism is sometimes evoked in a more positive way. When Dennis “Cutty” Wise is released from prison and finally escapes the drug trade to open a community boxing club, his new optimism is underlined during an election day jog, accompanied on his walkman by Curtis Mayfield’s “Move On Up,” a significant moment of scoring in a series that largely eschews the use of a musical soundtrack. Such optimism is undercut, however, when Cutty is canvassed and admits that as a former felon he is barred from voting, a mechanism that further disempowers the underclass.

State senator “Clay” Davis (Isiah Whitlock Jr), a key character in the series.

In this depiction of black Baltimore, echoes of the ’60s are weak — considering the scale and dynamism of the upheavals that shook the United States and the world in that era, when masses marched against war, racism, sexism, and imperialism. The Wire cannot make present, however, what is absent or attenuated in the wider culture that it represents. The script gives a strong sense that this movement has been both co-opted and defeated. The residue of the Civil Rights Movement seems to have left in Baltimore a lack of confidence in collective action, a lack of faith in alternative possibilities.

This hollowed out political landscape is very much in keeping with the post–9/11 atmosphere, and direct references to new powers available to police emerge at a crucial moment in The Wire, showing how the FBI reordered its priorities from drug investigations to the “war on terror.” In one instance, an Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) agent points out a sign for the Department of Homeland Security and asks McNulty if he feels any different. McNulty admits that he didn’t vote in the 2004 election, because neither George W. Bush nor John Kerry had any idea of what was going on where he works.

Other plotlines bring in contemporary events. One journalist refers to a call that a colleague supposedly received from a serial killer and remarks that it must be strange to talk to a psychopath. In response, another reminds them that he interviewed Dick Cheney once. Another time, a woman in the city informs an old friend that her sister is working at a school in the county “teaching every n****r to speak like Condoleezza [Rice].” And as a police seminar on anti-terrorism descends into farce, one officer calls out, “Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job,” a reference to George W. Bush’s infamous post-Katrina comment to the head of FEMA. David Simon would in fact follow The Wire with a less successful series exploring New Orleans entitled Treme.

Iraq is a recurring point of reference, not only directly but analogically. The story of a homeless Iraq War veteran features in the final season. Police patrolling the streets of Baltimore compare the city to Fallujah, with one recommending the use of air strikes and white phosphorous. The “war on drugs” is portrayed in such a way as to mirror the war on terror. One sequence, for example, alludes to the twin towers of 9/11. After the demolition of two housing project towers indirectly triggers a protracted and pointless power struggle, one gangster says, “If it’s a lie, then we fight on that lie.”

As the series moves to its conclusion, various scenes evoke the beginning. In the final episode, Detective Leander Sydnor meets with Judge Daniel Phelan, just as McNulty did in the first episode. Detectives go to a crime scene in the low-rises where they find a body in the shadow of the same statue where the body of a witness murdered in season one was found. We see Michael become the new Omar, and Dukie become the new Bubbles. The concluding scenes, particularly the final montage, are marshaled to show that the police department, drug trade, school system, newspaper, and city hall all carry on in the same way. No matter what characters have risen or fallen or died, the cycle continues and the system survives.

The series is more diagnostic than prescriptive. Nevertheless, Simon has said that he intended the show to be a political provocation. As interviewers ask what sort of political response he means to provoke, he has replied that he is not a social crusader, claiming to be a storyteller coming to the campfire with truest story he can tell. What people do with that story, he said, is up to them. Simon admitted at the time, however, that he was pessimistic about the possibility of political change as he found the political infrastructure bought, journalism eviscerated, the working class decimated, and the underclass narcotised. By contrast to the president elected as the series concluded, he said The Wire exhibited the “audacity of despair.”

While occasionally Simon indicates politicians lack courage to take on real problems, ultimately he sees the problems as rooted in systemic failure. Underlying The Wire’s story arc is the conviction that social exclusion and corruption do not exist in spite of the system but because of it. Its skepticism about reform comes from recognising that substantive social change is not possible “within the current political structure.” Simon has declared the series to be about “the decline of the American empire.”

A political drama

In a session at the Paley Center for Media (formerly the Museum of Television and Radio), Ken Tucker introduced Simon as “the most brilliant Marxist to run a TV show.” While Simon did not contradict Tucker, he has elsewhere asserted that he is not a Marxist. When asked if he is a socialist, he has declared that he is a social democrat. He believes that capitalism is the only game in town, that it is not only inevitable but unrivalled in its power to produce wealth.

However, he opposes “raw, unencumbered capitalism, absent any social framework, absent any sense of community, without regard to the weakest and most vulnerable classes in society — it’s a recipe for needless pain, needless human waste, needless tragedy.” Simon is for radical redistribution — “no trickle down bullshit” — but not “to each according to his needs” either. He took this perspective into the 2016 US election cycle, saying that he welcomed Bernie Sanders, who was “rehabilitating and normalising the term socialist back into American public life,” but he opposed attacks on Hillary Clinton that he felt spoke to “presumed motives” rather than “substance.” Bernie Sanders, he said, should “lead the left-wing” of the Democratic Party.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, class struggle is largely absent from The Wire; characters struggle individually, but there is no sign of concerted collectivity likely to emerge as a counterforce of significant consequence. In an interview with Matthew Iglesias, Simon said he identified with the social existentialism of Camus: to commit to a just cause against overwhelming odds is absurd, but not to commit is equally absurd. Only one choice, however, offers the slightest chance for dignity.

The Wire told a “darker, more honest story on American television… indifferent to the calculations of real estate speculators, civic boosters and politicians looking toward higher office.” Simon is “proud of making something that wasn’t supposed to exist.”

What Simon thinks of Marxism is one thing (and it is not always clear), but what Marxists think of him is another. The Wire is a Marxist’s idea of what TV drama should be. Its specific plots open into an analysis of the social-political-economic system shaping the whole. The series has demonstrated the potential of television narrative to dramatise the nature of the social order, a potential that TV drama has long neglected or inadequately pursued.

In probing the parameters of the intricate interactions between multiple individuals and institutions, the complex script, seen over all the seasons, excavates the underlying structures of power and stimulates engagement with overarching ideas. It bristles, even boils over, with systemic critique. While it offers no expectation of an alternative, it provokes reflection on the need for one, and an aspiration toward one. It may not have been written by Marxists to dramatise a Marxist worldview, but it is hard to see how a series written on this terrain by Marxists would be much different from The Wire.

Helena Sheehan is emeritus professor at Dublin City University. She is the author of Marxism and the Philosophy of Science and Navigating the Zeitgeist.

Sheamus Sweeney is a recovering academic who completed a PhD on the representation of Baltimore in the work of David Simon.

This article was first published on Jacobin.

Featured image: HBO