New Delhi: Ease of access to LPG cylinders, lack of awareness around hazards of indoor pollution, and high prices of cylinders are some of the factors that are discouraging women in rural and poor households from using LPG cylinders as opposed to traditional cooking fuels, a new study has found.

Citing the detrimental effects of traditional cooking fuels on women’s health as well as the environment, the Union government launched its flagship scheme the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) in 2016 with an aim to make clean cooking fuel available to rural and low-income households.

The objective of the scheme was to make clean cooking fuel such as LPG “available to the rural and deprived households which were otherwise using traditional cooking fuels such as firewood, coal, cow-dung cakes, etc”.

A study conducted by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in collaboration with ASAR (Asar Social Impact Advisors Pvt Ltd), a social and environmental impact start-up in India, was published on Monday, August 21, that assesses and identifies strategies to reduce household air pollution and mitigate the damage to health and environment.

The study titled Barriers to Access, Adoption, and Sustained Use of Cleaner Fuels Among Low-Income Households: An Exploratory Study from Delhi and Jharkhand, India was conducted using 10 focus group discussions and nine in-depth interviews in five urban slums of Delhi (both notified and non-notified bastis) and five in villages in rural Jharkhand with women above 18 years of age, who are primary fuel users.

Findings of the study

The study found that the use of different fuels depends on their “ease of access rather than ease of use”.

It stated that in the notified bastis of Delhi for instance, “women are primarily using LPG, whereas those in non-notified bastis rely on biomass as they are unable to access LPG. In Jharkhand, women largely use biomass as it is easily available to them, and only women with regular incomes use LPG as the primary fuel”.

The study said that Jharkhand and Delhi were chosen for the study as the two states with the highest and lowest use of solid fuel for cooking in India (as per the fifth round of the National Family Health Survey) – Jharkhand (67.8%) and Delhi (0.8%) respectively.

The study also found that while schemes like Ujjwala Yojana have been undertaken by the government to reduce the impact of cooking fuels on women’s health, women are not aware of the adverse health impacts of household air pollution.

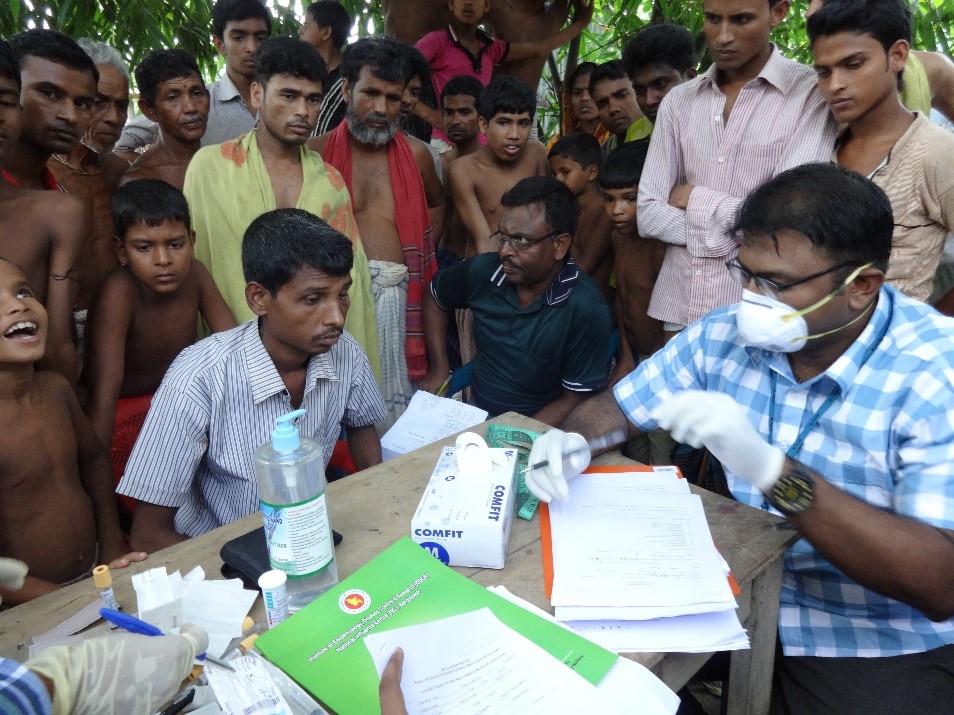

Prime Minister Narendra Modi distributes the free LPG connections to the beneficiaries, under PM Ujjwala Yojana in Ballia on May 1, 2016. Union Minister for Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Kalraj Mishra is also seen. Photo: PTI

“They do not consider indoor smoke due to biomass burning as pollution, but rather see it as a temporary discomfort which does not have long-term health implications,” the study said.

In a reply given to Rajya Sabha during the monsoon session, minister of state of the ministry of petroleum and natural gas Rameswar Teli said that as on July 1, 2023, there were 9.59 crore beneficiaries of Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY).

The study said that the high price of LPG cylinders coupled with the fact that they need to be paid for in one go makes it unaffordable for people from low-income households.

Teli had also told the Rajya Sabha in a written reply that under the scheme the Union government bears an expenditure of upto Rs 1,600 per connection for Security Deposit (SD) of Cylinder, Pressure Regulator, Suraksha Hose, DGCC booklet, and installation charges.

Also read: Since 2016, PMUY Beneficiaries Consuming Less LPG Than Non-Ujjwala Consumers: RTI Data

“PMUY beneficiaries have an option to choose from 14.2kg Single Bottle Connection(SBC)/ 5kg SBC/ 5kg Double Bottle Connection (DBC). Further, government has started a targeted subsidy of Rs. 200 per 14.2 Kg cylinder for Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) beneficiaries for upto 12 refills for year 2022-23 and 2023-24,” he further said.

In recent months, the price of LPG cylinders have skyrocketed.

In a separate reply on the increasing prices of LPG cylinders, Teli said that the price of “domestic LPG (at Delhi) was Rs. 1053 w.e.f. 6th July 2022 and is Rs. 1103 in July 2023. For PMUY consumers effective price is Rs. 903 after a targeted subsidy of Rs. 200 per cylinder”.

According to a report in The Financial Express FY19 and FY20, the average number of LPG refills per year was three bottles, which rose to 4.4 bottles in FY21. In the subsequent two years, it dropped to around 3.7 refills per year.

The report also noted that this decrease reflects the stagnant income levels among the beneficiaries. However, it added that some smaller households may not require more than four refills annually.

In August 2022, Teli told the Rajya Sabha that 9.2 million customers did not take any refill in 2021-22. The Union government had admitted that the PMUY beneficiaries had not been able to fill cylinders due to the high prices of LPG.

The study said that women face other systemic issues in accessing LPG.

This includes “the inability to furnish documents to apply for gas connections (especially in non-notified bastis in Delhi where people struggle to provide address proof), delays in processing applications, lack of doorstep delivery in rural Jharkhand and non- notified bastis of Delhi, and poor grievance redressal which makes their transition to cleaner fuels tougher.”

In addition, women were also found to be reluctant in using LPG fuel as perceptions and social norms act as deterrents. The study said that women were found to believe food cooked on LPG “causes gastric issues, it does not taste good, and that LPG is unsafe to use.”

Recommendations

The study has recommended the implementation of behaviour change and awareness campaigns along with building local-level baseline data on the households’ pattern of fuel usage to identify groups of people who should be targeted for interventions to promote the shift to clean cooking fuels.

In addition it has also recommended doorstep delivery of LPG cylinders as well as support with documentation to extremely vulnerable households.

“This study, supported by USAID’s Cleaner Air and Better Health project, will enable us to frame

policies and programs to match the needs of target populations, with a focus on gender inclusion,” said USAID/India’s Environmental Advisor, Soumitri Das in a press release.

“We need continuous and sustained interventions at both demand and supply levels to address the issue,” said Neha Saigal, Head of the Gender and Climate Programme at Asar Social Impact Advisors.