After the trauma of 1857, literature on the Mughal court acquired an unreal quality and was projected as an idealistic world to denounce the British Raj.

After the trauma of 1857, literature on the Mughal court acquired an unreal quality and was projected as an idealistic world to denounce the British Raj.

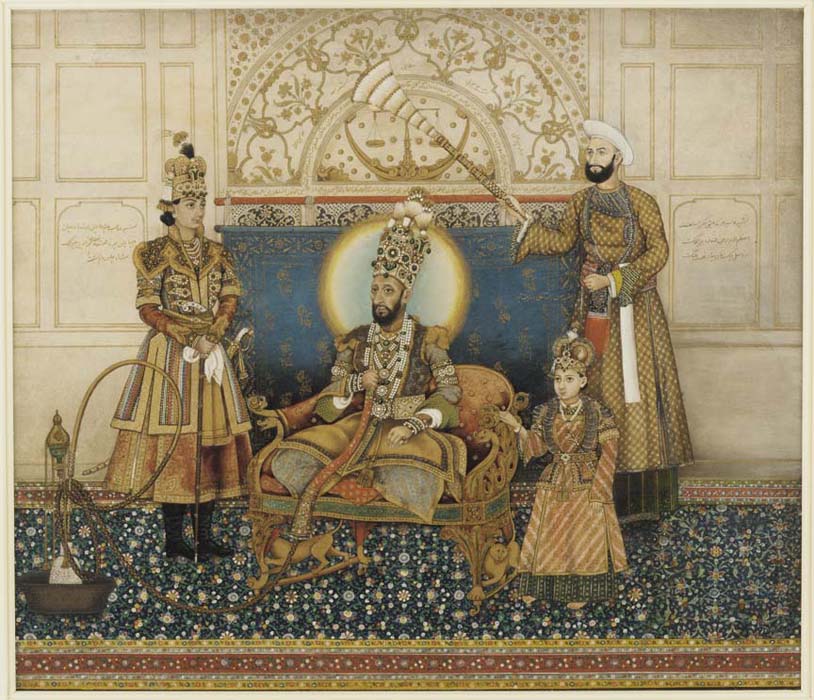

Bahadur Shah II enthroned with Mirza Fakhruddin. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

How we write about our past is tied intimately to our own time and place. As we seek to define ourselves by our history, our present day concerns often deeply colour our perceptions of that history. No wonder the past is such a strongly contested field of enquiry. This issue is well reflected in a particular body of writing in Urdu, published between the 1880s and the 1930s. These works sought to capture the culture of the Mughal court, as it had existed before the revolt of 1857. The content, style and tone of these popular histories tells us as much about the authors and their times, as it does about the past they present to the reader. New editions of several of these have been published by the Urdu Akademi, Delhi, in the last few decades. However, no English translations have been published.

It is interesting to compare the first work in this genre of popular history writing – Munshi Faizuddin’s Bazm e akhir (literally, ‘the last gathering’), published in 1885 – with one of the last to be published – Syed Wazir Hasan Dehlvi’s Dilli ka akhri deedar (literally, ‘the last sight of Delhi’). Not much is known about Faizuddin, except that he was an employee of Mirza Ilahi Baksh, who was a close confidant of the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar and the father-in-law of the emperor’s son. Due to Ilahi Baksh’s membership of the inner circle of the Mughal court, Faizuddin had seen life in the Mughal court and family at close quarters. Interestingly, the first edition of the book carried an endorsement by a prince of the royal family, asserting the authenticity of the account.

His is a richly detailed account of the daily life of the emperor, his extended family and household. It makes for fascinating reading and is an important source of information for this period of Mughal history – particularly court ritual, the beliefs and practices of the Mughal royal family, the festivals celebrated by them – all related in an anecdotal style. At the same time, its curious silences stand out. There is no mention at all of the East India Company, even though it was the de facto ruler of Delhi at the time and was making deep inroads into the Mughal court as well. After all, Bahadur Shah ‘Zafar’ himself succeeded to the throne, in spite of his father’s wishes, due to the support of the British.

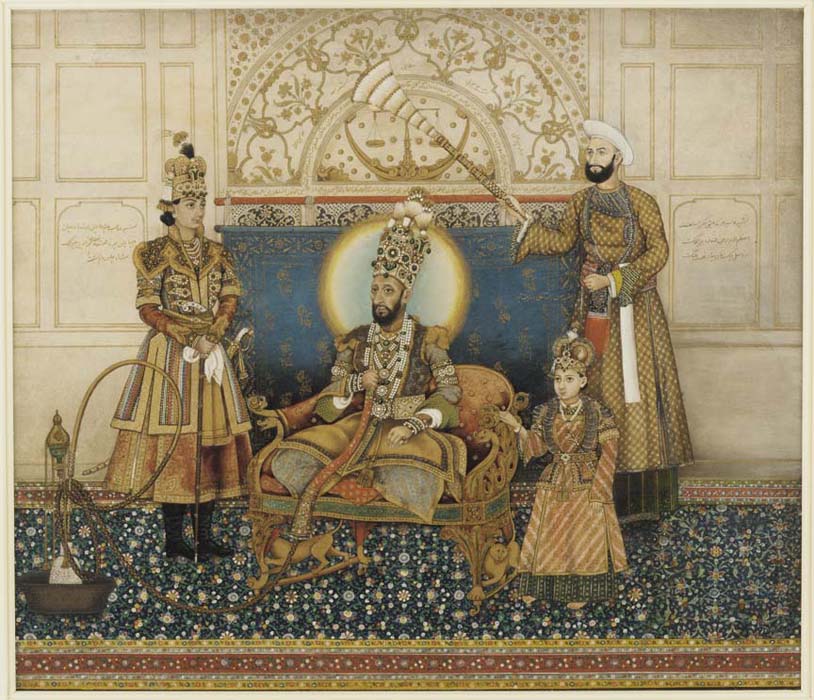

The fact that Munshi Faizuddin chose not to speak of the colonial state, should not surprise us. The revolt of 1857 had invited exemplary punishment on Delhi – many of its residents were massacred or executed after summary trials, many more had their properties confiscated, were driven out and ended up migrating to other towns and cities to build their lives afresh. The terror of the reprisals was so deeply imprinted on the minds of the generation that lived through it, that more than 25 years later, Faizuddin could not bring himself to talk of the East India Company’s rule in Delhi. The fact that a quarter of a century had to elapse before anyone wrote about the Mughal court was an indication that in the immediate aftermath of the revolt its was considered unwise to even mention Bahadur Shah, his court and his family.

A slightly different kind of writing was to surface in the early 20th century. This came from the pens of a younger generation, many of whom were well known literary figures. Though born in families that had seen the revolt, they themselves were separated from it by a generation or two. They relied on the memories of their elders for their accounts – though one suspects that sometimes the tales of an ‘old grandmother’ was used as a literary device.

The siege of Delhi in 1857. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

One of these later works is that of Syed Wazir Hasan Dehlvi, the grandson of the famous novelist ‘deputy’ Nazir Ahmad. The short book is a collection of essays based – the author says – on things read in books and heard from elders. His descriptions of rituals and practices and the life in the Mughal court, often seem to have been taken from sources such as Munshi Faizuddin’s work. They are therefore much the same.

Where he goes beyond the earlier work, is in the nature of his authorial commentary. There is explicit comment on the significance of Mughal rule and implicit comparisons to the present. For instance, he says of the Mughals, that they “did not merely conquer Hindustan but made it their own country and beloved home, and as a person adorns his house according to his capacity, they too transformed it with their language, administration, architecture, way of living, learning, music, poetry, knowledge and talents.” Wazir Hasan uses the voice of an old lady, Aghai Begum, for a variety of social and political comment. She points out that, nowadays, despite there being plentiful rain and abundant crops, there is repeated famine. This is because, to quote her, “whatever we have is taken away in sackfuls”. Earlier, in her words “ghar ka paisa ghar hi mein tha” (the wealth of the home, remained in the home). This was obviously a critique of the drain of wealth under British rule, which Wazir Hasan could express indirectly through the words of the old lady.

In the 1930s, when the work was published, the freedom movement was nearing a crescendo. Memories of Mughal rule, long buried in the trauma of 1857, could be invoked to denounce the British regime. This political agenda exaggerates the nostalgia in Wazir Hasan’s work and there is a strong tone of pathos when speaking of a culture that is past.

Both authors, constrained by their own place in history, separated by both time and circumstances, write accounts of the late Mughal court and culture that differ in important particulars, but at the same time share a certain unreal quality. The picture they paint is vivid but somehow unreal – idealised and frozen in time. In the case of Faizuddin, this is because the removal of the East India Company from the scene he depicts, makes it ahistorical. In the case of Wazir Hasan, the desire to show the Mughal world as being in every way better than his own, makes it equally unreal.

Part of the problem also lies in the trauma of 1857, which swept away the Mughal court, and left behind memories that would forever be seen through the prism of the upheaval, as a late lamented ideal world. Those who had lived through the revolt, or their descendants, could not be objective about it. It is important to keep this in mind when reading these accounts as a source for the history of late Mughal Delhi.

Swapna Liddle wrote her PhD thesis on the cultural and intellectual history of nineteenth century Delhi. She is the author of Delhi: 14 Historic Walks, and Chandni Chowk: The Mughal City of Old Delhi