They can have millions of parties in the moonlight that I will not go to

— Vinicius de Moraes, “Você e Eu”

Getz/Gilberto

Spring ’64, was when the forests rumbled and the streets caught fire. Cassius Clay became Muhammad Ali. Elvis was discharged from the army. The British, dressed up as four boys in mop-tops, invaded the Americas. And in Brazil, the army, aided by the ever-dependable CIA, overthrew President João Goulart in what turned out to be the start of 21 years of military dictatorship.

Yet, a quieter invasion began that same spring, when another Brazilian, also called João – that sticky Portuguese J, whispered through coffee and cachaça – released an album with a jazz saxophonist from Philadelphia. The record had a memorable cover, painted by the Puerto Rican abstract expressionist Olga Albizu, all flaming amber and Titian gold on heavy black. It had a memorable name, a harmonic and alliterative name, those of its creators, Stan Getz and João Gilberto. And it had a memorable sound, a new thing, new beat, bossa nova, the sound of warm rain and afternoons on the beach in the shadow of the Sugarloaf Mountain.

‘Getz/Gilberto’ was one of the first two CDs I owned, acquired almost four decades after its original March 1964 release (the other was Parlophone’s reissue of ‘With the Beatles’). Like most of the non-Portuguese-speaking world, this was my first affair with Brazilian music. I knew vaguely of samba, because, being Bengali, enthusiasm for the Brazilian football team was thrust upon me. And I was beginning to get a taste for jazz, so I really dug Stan Getz.

But this, this was something else entirely, this syncopated love-child of Debussy, jazz and samba. It was sickeningly melodious, but also kinda off-key (as the fourth song on the album, ‘Desafinado’, or “out of key” in Portuguese, admits with a wink). It sounded happy, but also wistful, as if it had forgotten a beloved hat in the back of a taxicab and regretted it just a little. Seductive as hell, it all but buried the attendant whiff of danger under irony and mesmerism. It was, in other words, the perfect record to make fumbling, inexperienced love to, and I was head over heels in love the summer I discovered João Gilberto.

A poster of Joao Gilberto. Photo: Flickr/comunicom.es CC BY SA 2.0

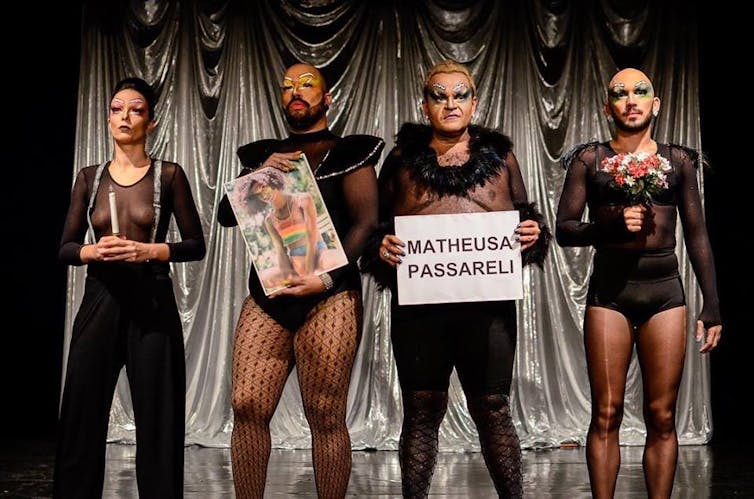

Orphic Rites

In Brazil, race clings to everything. For almost four hundred years, the Portuguese pressed both the indigenous people (the Guarani) and Africans into slavery; by the early nineteenth century, Africans outnumbered Portuguese settlers by three to one in northeastern states like Bahia (which is where, on June 10, 1931, Gilberto was born). Even today, dark-skinned Brazilians are disproportionately subject to institutional violence and unequal distribution of wealth.

However, in the 1930s, a number of scholarly works began interrogating this idea of race, politics and national identity, and celebrating mixing of races as something fundamental to the Brazilian character. In Roots of Brazil, the sociologist Sérgio Buarque de Holanda – father of the singer Miúcha, who married João Gilberto in 1965, and of the musician Chico Buarque de Holanda – suggested that the essential Brazilian identity was that of “the Cordial Man,” ruled by the heart and basing everything on the “ethos of emotion.” And in his revolutionary The Masters and the Slaves, the anthropologist Gilberto Freyre acknowledged “the shadow, or at least the birthmark, of the aborigine or the Negro in every Brazilian”. “In our affections,” he wrote, “our excessive mimicry, our Catholicism, which so delights the senses, our music, our gait, our speech, our cradle songs – in everything that is a sincere expression of our lives, we almost all of us bear the mark of that influence.”

Also Read: Brazil’s First Indigenous Online Radio Station Promotes Native Languages and Communities

For scholars like Freyre and Buarque, Brazil, more than a political entity, is an affective state of being where everything is connected intimately, at a personal level. This is why Brazilians love Garrincha more than Pele (“Pele is revered. Garrincha is adored.” – Alex Bellos, Futebol: The Brazilian Way of Life). And this is why João Gilberto’s mistimed mumblings strike something delicate and raw somewhere deep inside, because they are reminiscent of the necessity and the fragility of human relationships. They are the link between the magnificent, utopian architectural folly that is Brasilia and Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed, even as they concede, all along, that repression and dictatorships are also intricate weaves in the elemental Brazilian fabric.

The Orphic rites of danger, death and excess that form the nervous system of Brazilian culture explode into trails of genius every once in a while. In 1956, the poet and diplomat Vinicius de Moraes’s three-act romantic tragedy Orpheus of the Conception, with music by Antônio Carlos Jobim – the greatest Brazilian composer of the 20th, or, indeed, any, century – premiered in Rio de Janeiro. A moody reimagining of the Orpheus myth, set in Rio during the carnival, it had voluptuous music in the vein of samba-canção, a slower, more lyrical samba. But samba, nonetheless. That’s when João Gilberto stepped in.

Nhenhenhem…

Gilberto’s contribution to the craft of Brazilian song is, frankly, absurd. He takes Jobim’s languid compositions and shuffles them into his guitar. The guitar swivels one way, his voice droops the other. He delays the vocals and advances the guitar. Then he does it the other way around. His guitar keeps brushing against chords in this bossa nova style of playing, much of it influenced by the legendary São Paulo guitarist Garoto (“Garoto is extraordinary and his guitar is the heart of Brazil,” Gilberto once said). Sometimes, he uses his voice to complete the harmonies on his “telegraphically syncopated guitar,” as the bossa nova historian Ruy Castro notes in Bossa Nova: The Story of the Brazilian Music That Seduced the World.

The voice of João Gilberto is a quiet revelation. It wanders, whispers, and often just wilts away, trailing off into plucked guitar strings. Gilberto sings every song like he’s humming to a sleepy canary on the windowsill. His enunciation and phrasing from Sinatra, his breathy tone from the Brazilian crooner Dick Farney, he always sounds casual, conversational, and unconcerned. “João is skilled at singing behind the beat, like many jazz singers, but his ability to phrase ahead of the beat is even more remarkable,” the music journalist Ted Gioia recently wrote. “Few singers attempt to push the beat in this manner, because doing so tends to impart a rushed and anxious quality to the music. It remains a mystery to me how Gilberto can propel the lyrics one bar or more ahead of the music, yet continue to sound so extraordinarily relaxed.” Or, as Miles Davis once said, “João Gilberto on guitar could read a newspaper and sound good.”

Also Read: Moralistic Pressures in Brazil Leading to Revival of Artistic Censorship

In a way, Gilberto’s sonic wobbling is an extension of all the dark arts performed by Cariocas over the ages. Rio is the only great world city where the poor look down on the rich, quite literally; the real estate gets more expensive the closer you get to the sea, so most of Rio’s low-income population lives in elevated favelas, unregulated slums on the hills near the Rio harbour. This visual-class counterpoint – the poor get the best views, while the rich pay for the beaches – is paralleled by the counterpoint between favela and asfalto. In the geographic imagination of the city, the asfalto is dull but safe, where the respectable people live; the favela is violent and diseased, but exotic, exciting, authentic! Gilberto’s stammering guitar (what the Brazilians call violão gago) and the temporal convulsions of his voice – just the barest suggestion of “an edgy fire behind the music’s calming melodies,” as Ed Morales describes it in The Latin Beat – gesture at just such a dialectic.

The Rocinha neighbourhood in Rio de Janeiro. Credit: Pilar Olivares/Reuters

“This isn’t music, it’s nhenhenhem,” Gilberto Sr. had once mocked. And why not? For a singer famous for his understated vocal sensitivity, João Gilberto is often unintelligible, even when you understand Portuguese. His fondness for gibberish and whimsy is evident from his very first album, ‘Chega de Saudade’ (No More Blues), released in 1959. The title track, written by Jobim and Moraes (who would become his frequent collaborators), is a nostalgic number about rejecting nostalgia. There are two Gilberto originals; nonsense phrases both, they are pure sonic utterances: ‘Hó-Bá-Lá-Lá’ and ‘Bim Bom.’

“It is not the right angle that attracts me, nor the straight, hard, inflexible line created by man,” the great Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer says in A Vida é um Sopro (Life is a Breath of Air). “What attracts me is the free, sensual curve. The curve I find in the rivers of my country, in the clouds up in the sky, in the body of my favourite woman. All the universe is made of curves.” Gilberto wrote ‘Bim Bom’ while watching Bahian laundresses pass by the São Francisco river with bundles of clothes on their heads.

Its rhythm is meant to replicate the swaying of their hips.

Saudade

For the Portuguese, and for Brazilians, who dream, sing and fornicate in it, saudade is a complex historical condition, a state of mind and a way of being. The 15th century king of Portugal Duarte the Eloquent called it a “failure of the heart” when it misses someone or something. It has connotations of nostalgia, loss, and the eternal sense of an absence. In the early 20th century, it became a symbol of the Lusophone spirit and culminated in the aesthetic movement of Saudosismo. Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet, for example, is soaked in saudade (“Senhor Valdes. I remember him now as I will in the future with the nostalgia I know I will feel for him then.” Or, “I’ll miss Moreira, but what does missing someone matter compared with a chance for real promotion?”).

Also Read: Jazz Isn’t Dead, It’s Just Moved to New Venues

The profound melancholy of the Portuguese fado, with its desolate lyrics and desperate voicing, often captured the yearning for home that many colonialists felt in Brazil in the 19th century. A rising political engagement with questions of nationalism in the 20th century led to the fado being left behind for the samba, that “national Brazilian music” (Hermano Vianna, History of Samba). Gilberto’s guitar twists the samba’s tail and infects it once more with saudade. No wonder, then, that ‘Chega de Saudade’ was the first great bossa nova release.

A photo of Joao Gilberto. Photo: Facebook

I tracked down all the João Gilberto (and Antônio Carlos Jobim) albums I could find obsessively – not very many, before YouTube and internet piracy – partly because I had begun to enjoy the music, but mainly because I wanted to facilitate the continuation of my love affair. There was something appropriate about this music. It was appropriate for loving, of course, but also for heartbreak. It worked as well for wino afternoons as it did for the hangovers to come. I played it at parties and I played it alone.

Obviously, I was about 40 years too late. An entire generation of Brazilian lovers had already grown up listening to João, from Gilberto Gil to Seu Jorge. Tropicalistas – the iconoclastic, discordant rockers of the repressive ’60s, many of whom were imprisoned or exiled – swore by him. “João Gilberto was the greatest artist that my soul came into contact with,” Caetano Veloso tweeted (after Gilberto’s death, on July 6). “Before I turned 18, I learned from him everything I already knew and everything that was yet to come.” The fourteen-year-old Gal Costa grew entranced by ‘Chega de Saudade’ when it first came out and decided to become a singer. In the middle of a concert in a sleepy mid-western town in the US some years ago, the psychedelic band Os Mutantes, fronted by the incandescent Rita Lee, broke into a medley from Gilberto’s second album, ‘O Amor, o Sorriso e a Flor’ (Love, the Smile and the Flower). All of us hummed along.

In his delightfully vulgar ode ‘A Bossa Nova é Foda’ (which translates roughly to ‘Bossa Nova is the F*****g S**t’), Caetano Veloso calls João Gilberto “the Wizard of Juazeiro” who gives the world the gift of bossa nova. Eccentric, reclusive, stage-fraught, cat-loving, saudade-stricken João Gilberto, without whom my teenage love would not exist, I want to give you a big hug. Or, as they say down on the beaches of Ipanema, João Gilberto, um abraçaço.

Sudipto Sanyal is assistant professor, department of English at Techno India University in Kolkata.