To commemorate the 125th birth anniversary of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, the Union government declared that January 23 will henceforth be observed as ‘Parakram Diwas’ or ‘Day of Valour’. This year, it came with a new plan to start the Republic Day celebrations from Bose’s birth anniversary on January 23. These developments have taken place amid long-standing demands to declare the day as ‘Desh Prem Diwas’ or ‘Day of Patriotism’, and it was being celebrated in West Bengal, Bose’s home state, as such since 2011.

It appears that the present Union government wishes to highlight Netaji’s contributions only as the head of the Indian National Army challenging the British government with arms. This goes in line with some other announcements around Netaji by the government including Moirang Day – April 14, INA Raising Day – October 21, the day Netaji went to Andaman and unfurled the flag – December 30 etc.

Bose was one of the most important leaders of the freedom movement whose popularity among the masses was perhaps second only to Gandhi. In India, where politics often gathers around larger than life figures, and history is contested not only in universities but also in political rallies, how the ruling regime is trying to portray one of the tallest leaders of the Indian freedom movement assumes importance.

In 2021, Prime Minister Narendra Modi made a speech to commemorate Netaji’s 124th birth anniversary in front of the Victoria Memorial Hall in Kolkata. It is important to read between the lines of the prime minister’s speech, since he himself, his government and his party, the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), are trying to establish that the previously neglected Netaji is getting a canonical space in the freedom movement through their efforts only.

In that event, the prime minister said that on January 23, 1897, “India’s new military prowess was born.” He focused on the INA and how Netaji organised it taking great “risks” and making “sacrifices”. His emphasis was that Netaji had shown that the British “could be defeated by the brave soldiers of India on the battlefield”. The prime minister narrated how Netaji escaped from his Elgin Road house to flee the country but not before sending “his niece Ila to Dakshineswar temple to seek the mother’s blessings”. At the end, the prime minister also attributed a copy of the Bhagwad Gita (a Hindu religious text) to Bose which he kept with him and that inspired him in “flowing against the stream”.

The image that follows from the Prime Minister Modi’s description of Subhash Chandra Bose is of one austere Hindu militarist with no ideological leanings other than his own conviction in the “sacred goal”. This image contrasts sharply with the well-read, ICS qualified statesman Subhas Chandra Bose who presided over the Congress twice, represented his country at the highest of platforms and brought significant ideological energies to the Congress and the national movement.

It appears that Bose’s long political life, starting with his college days to the Kolkata Corporation to the national scene, has little (read no) relevance to the ruling dispensation and only his raising the INA and fighting the British militarily are noteworthy achievements. This image of an austere Hindu militarist, unconcerned about the means but focused solely on the end, fits the bill for the prime minister’s parent organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and its aggressive Hindu nationalist rhetoric. However, Bose’s life was much more complex and these attempts at placing him in the Hindu nationalist canon can only be called crude reductionist distortions to Netaji’s legacy and his place in the freedom struggle.

It would be beneficial in this context to examine Subhas Chandra Bose’s personality and work in some detail to better appreciate what he intended for his country he so greatly loved.

Also read: Modi’s Aim Isn’t to Pay Tribute to Netaji and the Ina but to Put Mahatma Gandhi in His Place

Unity among all Indians

When Bose was young, he spent much of his time wandering to find the ‘truth’. Visits to seers and Sadhus were a regular affair along with extensive debates on the spiritual and philosophical subjects among a group of friends. He dived deep into the works of Swami Vivekananda and such was the impact that he “was thrilled to the marrow”.

For further studies, his parents sent him to the burgeoning city of Calcutta and it was here that Bose started realising the futility of founding ‘the truth’. It was impossible for the young and sensitive Bose to remain aloof to the racial discrimination practised on the streets and trams of Calcutta. Conflicts of an inter-racial nature between Britishers and Indians were a ‘rude shock’ to him.

In July 1914, reports of the Great War filled newspapers and Bose started feeling “disillusioned about Yogis and ascetics”. Gradually, it started dawning on Subhas that “for spiritual development social service was necessary… which included the service of one’s country”. Glancing at his adolescence days in his autobiography, The Indian Pilgrim, Bose approvingly quoted Vivekananda saying “salvation will come through football and not through the Gita.” He went to Cambridge and cleared the ICS exam in 1920 but could not reconcile himself to the “principle of serving an alien bureaucracy” and resigned consequently.

His eagerness to serve the country was such that he went to see Mahatma Gandhi in Bombay the same afternoon he landed from England. Here, it should be noted that while most of his fellow-travellers in the Grand Old Party were awed by the charisma of Gandhi, “Mahatma had failed to cast his hypnotic spell on Subhas.” Cast in a different mold than his Congress brethren, Bose was the protégé of Chittaranjan Das, popularly called Deshbandhu, an esteemed lawyer, nationalist and leader of the Swaraj Party. It was C.R. Das who boldly announced as the president of the 1925 session of the All India Trade Union Congress that the Swaraj he wanted is for the ‘98%’.

Das’s work was remarkable on the front of Hindu-Muslim unity as well. Following the footsteps of Das, Bose also tried to solidify Hindu-Muslim unity, going far ahead from some of his compatriots in working to assuage the fears of the minority community. Though forming the plurality in Bengal, Muslims were far behind Hindus in the newly emerging professions, education and services. To rectify this, Das “proposed a pact between Hindus and Muslims for an equitable sharing of power and positions acquired by nationalists from the British” which the Bengal Provincial Congress Committee adopted.

When Bose became the chief executive officer of the Calcutta Municipal Corporation, he appointed a disproportionate number of Muslims in the corporation to break the Hindu monopoly. He was vehemently criticised for this but he remained firm behind the ‘just-claims’ of Muslims, Christians, and members of the depressed classes even at the cost of ‘heart-burning’ among the conservative Hindu sections. This act won him applauds from Das and Gandhi himself. Bose’s work on the Hindu-Muslim unity was such that it frustrated Vinayak Savarkar, the founder of Hindutva, who said that “Bose did not differ very much from Mahatma Gandhi, except that he went further to woo the Muslims.”

The socialist thrust was evident in Bose when he started attracting nationwide attention. It was evident after the Madras session of the Congress that Bose along with Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru were capturing the imagination of the nation’s youth and “they could see themselves as confreres in the left wing of the Congress”.

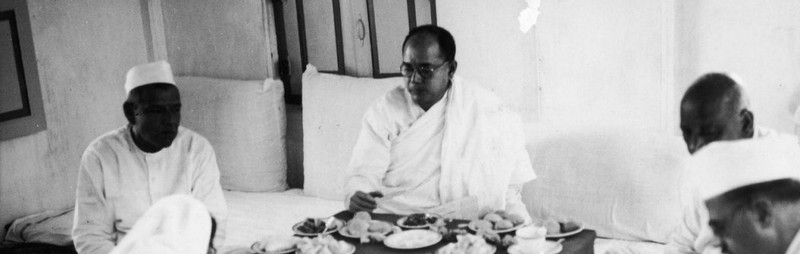

Subhas Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru and others proceeding to the AICC meeting from 1, Woodburn Park on October 1937. Photo: Unknown photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Mass appeal of these young leaders enabled them to broaden the Congress programme to include the demand of ‘complete independence’ instead of dominion status as demanded in the All-Party Nehru Report (1928). The Hindu-Muslim issue was becoming central to the future of the country with radical appeals from both the Hindu and Muslim side becoming shriller. To tackle the drift, Bose advocated “the dawn of economic consciousness [which] spells the death of fanaticism. There is much more in common between a Hindu peasant and a Muslim peasant than between a Muslim peasant and a Muslim Zamindar.”

The 1930s were the high point of Left unity in and out of the Congress. The Congress Socialist Party was formed in 1934 and Bose was in agreement with “its general principles and policy from the very beginning” and added that he sees it “desirable for the Leftist elements to be consolidated into one party.”

Bose worked a great deal to realise the unity of the Left – socialists, communists and the Royists – in the Congress. He believed that “without Left consolidation I do not see how we can arrive at real national unity.” He presided over the All India Trade Union Congress’ (AITUC) Calcutta session at a crucial juncture when the conflict between Leftists and Rightists was intensifying in the AITUC. He declared there that “I have no doubt in mind that the salvation of India, as of the world, depends on socialism.” When the clouds of the second World War were gathering and Bose was getting impatient with the Gandhi-led Congress’s lack of “revolutionary impulse”, he was firm that the “INC should be organised on the broadest anti-imperialist front, and should have the two-fold objective of winning political freedom and the establishment of a socialist regime.”

The undemocratic fiat exercised in the princely states was many a times ignored by Gandhian stalwarts due to several reasons like the personally cordial relations between some Gandhian leaders and many Princes and representation of the land-owning class. Bose’s stand was uncompromising here as he wanted the INC to guide the “popular movements in the States for civil liberty and responsible government.”

Watch: If Netaji Were Alive, He’d Attack Modi’s Attitude to Muslims; He Wanted Jinnah as India’s 1st PM

What Bose meant by socialism

It should be underlined here that socialism for Bose was not some vague ideal fancy. On many occasions he discussed what he means by socialism at length and had charted out programmes to achieve that goal. He wanted organisation of peasants and workers on socialistic lines, organisation of youth as Volunteer Corps, abolition of the caste system and organisation of women’s association to achieve freedom.

He clarified what he meant by socialism further as the president of the Congress Session at Haripura (1938). “If after the capture of political power national reconstruction takes place on socialistic lines – as I have no doubt it will – it is the ‘have nots’ who will benefit at the expense of the ‘haves’.” Eradication of India’s endemic poverty was the first item on his agenda for national reconstruction. For that, he wanted “radical reform of our land system, including the abolition of landlordism.”

The Congress’s approach to the question of the abolition of landlordism has been lacklustre and as Congress president, Bose gave it a definite, progressive direction. Many in the Congress right-wing represented the interests of the landed classes but more than them, Bose’s roaring call to abolish Zamindari sent chills to the Muslim League, the Hindu Mahasabha and the RSS since these organisations primarily depended on the reactionary class of Zamindars for their coffers.

Moving from agriculture, the next item on his socialist agenda was “comprehensive scheme of industrial development under state ownership and state control.” To that end, Bose advocated a Planning Commission for “gradually socialising our entire agricultural and industrial system in the sphere of both production and distribution.” Bose eventually formed a National Planning Committee to chart the future course of Indian society and economy. His Leftist comrade Nehru was made chairman of this body. It’s clear as day that the programme of Bose was diametrically opposed to the practices of incumbent Modi regime which has abolished the Planning Commission Bose established. The BJP government is pursuing rampant privatisation and selling national resources to a few cronies while Bose wanted the ‘have-nots’ to benefit at the expense of the ‘haves’.

At Haripura itself he explained that “there is an inseparable connection between the capitalist ruling classes in Great Britain and the colonies abroad. As Lenin pointed out long ago, reaction in Great Britain is strengthened and fed by the enslavement of a number of nations. The British aristocracy and bourgeoisie exist primarily because there are colonies and overseas dependencies to exploit. The emancipation of the latter will undoubtedly strike at the very existence of the capitalist ruling classes in Great Britain and precipitate the establishment of a socialist regime in that country.”

Bose thundered further, “We who are fighting for the political freedom of India and other enslaved countries of the British Empire are incidentally fighting for the economic emancipation of the British people as well.” This excerpt makes it apparent that Bose had a deep understanding of the functioning of colonialism and was connecting the people of colonies to those of the metropolis in a united struggle against capitalism. He unequivocally declared that he “stands for socialism – full-blooded socialism” with a significant qualifier that “India should evolve her own form of socialism as well as her own methods.”

Meanwhile, communal sectarianism was raising its ugly heads and fanatics from both the Hindu and Muslims sides were consolidating the conservative sections of both the communities behind their respective banners. Earlier, as president of the Congress, Bose had banned the membership of the Congress to those who are members of communal organisations like the Hindu Mahasabha and the Muslim League.

The League under M.A. Jinnah had already passed the Lahore Resolution demanding Pakistan in March 1940. The reigns of the Hindu Mahasabha were in the hands of Vinayak Savarkar who also believed that Hindus and Muslims constitute two separate nations and was trying to organise Hindus against Muslims in North India and Bengal. “Subhas Chandra Bose did not seem to have been entirely persuaded by the mainstream Congress discourse on a singular nationalism exemplified by Jawaharlal Nehru.” He was for greater flexibility in the matters of religion but communal fanaticism was absolutely intolerable for him. He noted that Savarkar “was only thinking how Hindus could secure military training by entering Britain’s army in India” and “Jinnah was then thinking only of how to realize his plan of Pakistan (division of India) with the help of the British.”

Bose came to the “conclusion that nothing could be expected from either the Muslim League or the Hindu Mahasabha” for Indian independence.

File picture of Nehru, Mountbatten and Jinnah. Photo: Wikipedia Commons, public domain

The secular leadership

Around the same time, in Bose’s home province of Bengal, the Hindu Mahasabha was trying to polarise society and make headway among Hindus in the leadership of Syama Prasad Mookerjee, the founder of Jana Sangh and an icon of the Hindu right-wing. About that atmosphere, Bose wrote with concern that “thanks to the Hindu Mahasabha and to papers like the Amrita Bazar Patrika that have suddenly developed a rabid communalism, communal venon is being emitted from day to day, with a view to poisoning the minds of the Hindus in Bengal and elsewhere.” It appears that Syama Prasad and the Hindu Mahasabha came in conflict with Bose in the initial period itself.

Also read: Despite Appropriating Netaji, the BJP Continues to Disregard His Secular, Pluralist Worldview n

Syama Prasad recorded in his diary that “when we started organising ourselves [Hindu Mahasabha], Subhas once warned me in a friendly spirit, adding significantly, that if we proceeded to create a rival political body in Bengal he would see to it (by force if need be) that it was broken before it was really born.” It appears that Syama Prasad’s fear were not for nothing as he alleges that a public meeting they organised was “broken up by the hired agents of Subhas.” Syama Prasad’s contempt for the secular leadership Bose was giving to Bengal is visible in his slanderous accusations that Netaji was “scheming performances for keeping the [Calcutta] Corporation under his thumb”, and was lucky to get arrested in the Holwell monument case.

When Bose was organising the Left and working to bridge the widening communal chasm, Savarkar expressed contempt that Bose and his group is “obsessed with this mirage of Hindu-Muslim unity.” It is ironic and showcases the ideological bankruptcy of the Hindu right that the heirs of Syama Prasad and Savarkar are trying to pull Bose in their camp who so vehemently opposed their organisation and communal operations from the very beginning.

His escape from his Elgin Road house and reaching Germany is part of nationalist legends now. Subhas Chandra Bose taking Hitler’s assistance in his efforts to free India was perhaps the only act in his long public life that has some semblance with the RSS and the Hindu right. Here also, some evidence has emerged suggesting that before reaching Berlin, Netaji wanted to receive Soviet Union’s assistance with the support of the Communist Party of India. He tasked his nephew Amiya Bose to carry a secret letter to London to pursue that end.

During deliberation on this course of action, Netaji reportedly said “Soviet Russia could be trusted not to take advantage and occupy the country”. This plan did not work out as intended and Bose had to land in the company of Hitler. On the other hand, admiration for Hitler and his methods has been a constant theme in Sangh circles. However, they thought their energies are spent best in organising Hindus against Muslims and did nothing for Indian independence, with or without Hitler. Due to Bose operating from Fascist territory “there seemed no love lost between Subhas” and Leftist factions in and out of the Congress in India.

With great difficulty, Subhas managed to set a ‘Azad Hindustan’ radio. He raised the India Legion in Berlin numbering around 4,000 men with the springing tiger of Tipu Sultan – much despised by the Hindu right – adorning the Legion’s banner. Bose was fully aware of the international notoriety of the Hitler and his allies. He was seeking an intervention in the form of an endorsement of India’s independence from Germany, Italy and Japan but understood the ramifications of associating with these totalitarian ideologies. He distanced himself from the ideological programmes of Hitler, Mussolini and Tojo in a rare act of courage. He declared in a broadcast from Berlin that “my allegiance and my loyalty has ever been and will ever be to India and India alone, no matter in which part of the world I may live at any given time.” He was conscious as to not act as “an apologist of the Tripartite Powers” and stated in clear terms that he is not the person to defend their actions.

Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose with members of the Azad Hind Fauj, circa 1940. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Netaji taking command of the INA and making East and South Asia his theater of war is well recorded in military history. While leading the army, Subhas was also trying to make common cause with the ongoing struggles in the country. The first division of the INA under Mohammad Zaman Kiani was divided into brigades and “named after Gandhi, Nehru, and Azad in a deliberate effort”. The motto of his Azad Hind provisional government (Arzi Hukumat-e-Azad-Hind) was in Hindustani bordering Urdu: Ittehad, Itmad aur Qurbani (Unity, Faith and Sacrifice).

Back home, neither the Congress nor the Left were making efforts for enlistment in the British army. While most of the Congress leadership was in jail, the communists were soon to engage in relief work in Bengal. However, Savarkar was bent on making the most of the war for his organisation, the Hindu Mahasabha. He noted that “Japan’s entry into the war has exposed us directly and immediately to the attack by Britain’s enemies… Hindu Mahasabhaits must, therefore, rouse Hindus especially in the provinces of Bengal and Assam as effectively as possible to enter the military forces of all arms without losing a single minute.”

It’s clear from this position of Savarkar that he was most keen on recruiting ‘Hindus’ for the British, primarily in the areas Netaji intended to liberate with his INA. The Hindu right-wing’s politics has thoroughly remained one of contempt to Netaji, his mission and his ideology.

The glorious victory in defeat for Netaji and his INA was felt all over India when the INA men were tried in the famous Red Fort trials. During the course of these public trials, newspapers columns were filled with the stories of the brave men and women of the INA and their Netaji. Congress formed a defense committee for the INA which included Bhulabhai Desai, Asaf Ali and Jawaharlal Nehru. Congress and communists publicised the details of trials and the bravery of the Indian prisoners of war under Bose.

At this time, Nehru noted that apart from the legalities, this was “a trial of strength between the will of the Indian people and the will of those who hold power in India.” The communist leadership “without shifting an iota from their inflexible anti-Fascist stand…regretted sincerely certain epithets used about Netaji.” In fact, it were the communists with the Forward Bloc who carried forward Netaji’s work whether through the Calcutta strikes (November 1945 – February 1946) or through their unflinching support and call of huge general strike in supporting the strike of the naval ratings during the Royal Indian Navy mutiny (February 1946) in Bombay.

Netaji’s personal life

This analysis of the life and work of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and his contemporaries leaves no doubt in mind that Bose was made of a different steel, incompatible with the claims of the incumbent Hindu right-wing. He was a spiritual person but abhorred communalism of any shade and termed the Hindu Mahasabha “a counterblast to the All-India Moslem League” with both trying to mobilise the conservative sections of their respective communities. He doubted their nationalist credentials many a times and believed that infighting between Hindus and Muslims is only going to strengthen the British.

Contrary to the belief and propaganda of the current Hindu nationalist dispensation which dubs the Mughals as Muslim invaders bent on destroying the Hindu culture, Bose wrote that under Mughal rule India “reached the pinnacle of progress and prosperity”. Praising Akbar, he wrote that the “state machinery which he built up was also based on the whole-hearted cooperation of the Hindu and Mohammedan communities”. Netaji also tried to achieve this cooperation in his own political life and in the functioning of the Indian National Army under very different circumstances. The RSS is infamous for not allowing women members and Savarkar, the high-priest of Hindutva advocated ‘rape as a political tool’. These go directly in opposition to Netaji’s belief in building women’s organisations and their liberation from servitude. In his Indian National Army, he made a women’s brigade under Captain Lakshmi Sehgal named after the Rani of Jhansi.

On a different question regarding the personal life of Bose, it would be interesting to see the reactions of the Hindu right since it has routinely ridiculed and insulted Rajiv Gandhi, Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi for their foreign connections. Their nationalist credentials have been questioned by the Hindu right solely on the basis of Sonia’s foreign origins and Rahul’s half foreign ancestry. Netaji married an Austrian woman, Emilie Schenkl whom he loved deeply. Not only Bose’s secularism, socialism and patriotism, his personal life is also hard to digest for the Hindu right and their narrow worldview.

To conclude, in trying to appropriate and laud Bose “the RSS motive is certainly not to praise Subhas but to denigrate Nehru”. Independent India is built on the solid secular, democratic foundations of the freedom struggle. Having no part in that fight against the British, the empty benches of the Hindu right in the pantheon of freedom fighters perennially haunt them. The crisis of legitimacy and lack of association with independence movement forces the RSS to look for icons on the other side of the political spectrum and try to appropriate them by reducing their image and work to fit the Hindu nationalist sectarian framework. They are doing this with Congress stalwarts like Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Madan Mohan Malviya and with the revolutionary Bhagat Singh.

Highlighting the military aspect of Bose’s personality, his Hindu credentials and spiritual drive to further the undemocratic agenda of aggressive Hindu nationalism and gaining a foothold in Bengal is fracturing and insulting the legacy of the secular, socialist and democratic Subhas Chandra Bose. Netaji Subhas was nothing like the aggressive Hindu militarist the Hindu right-wing is projecting him to be in the leadership of the prime minister himself. Reducing Netaji to mere slogans of ‘Khoon’ and ‘Azaadi’ and using his tactical disagreements with other leaders of the freedom movement to further the RSS agenda is misrepresenting and discrediting his life’s work. It needs to be said that when the statue of Subhas Chandra Bose – in full military uniform with a sword by his side – will be unveiled replacing Amar Jawan Jyoti by a right-wing regime, India would move further away from the teachings and message of our beloved Netaji.

The ‘Prince among Patriots’ was a fighter for the working classes, the peasants, the youth, the students and the women of this country. He was a crusader for communal harmony and Hindu-Muslim unity. All of these sections stand threatened today because of the aggressive, monolithic right-wing Hindu assault. It is opportune that we move by the “philosophy of activism” of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and the love he had for the men and women of his country in claiming the republic back and try build the “full-blooded socialism” he envisioned.

Vivek Sharma is a student at the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He tweets @imVivekSh