As a species, we humans are inveterate pattern makers. We’re also plagued by recency bias – the tendency to give more weight to things that have only just happened. Hardly surprising, then, that when analysing party politics, we tend to take the results of the latest elections and try to fit them into a trend.

That’s why the results of the recent election in Germany have caused a tailspin. The country looks set to have its first social democratic chancellor since 2005 after Olaf Scholz’s party emerged as the biggest in the Bundestag. That, in turn, has led at some point to the fact that the centre-left now governs a whole bunch of countries we’re very familiar with – and to wonder whether conservatives everywhere are in trouble.

It’s a good question. But to answer it, we need to first qualify what we mean by “conservative”. All too often it’s used to describe parties who would reject the label themselves. That’s certainly the case for the Christian Democratic Union of Germany and the Christian Social Union in Bavaria (CDU/CSU) – the big losers in the German election.

Christian democracy, in Germany and elsewhere, such as the Netherlands, Spain and Ireland, is a very different beast to conservatism and liberalism. It is as concerned with the “social” as it is with the “market” side of the social market. It is profoundly internationalist and with a view of society ultimately rooted in notions of community and family rather than the sovereign individual.

That’s why, when we’re trying to analyse trends, it’s arguably more helpful to talk about the mainstream right. This portmanteau term allows us to pick out those parties which (unlike parties of the left) have tended to govern in the interests of more comfortably off and/or socially traditional voters, but which (in contrast to the far-right parties on their flanks) regard the norms of both liberal democracy and the liberal international order as givens.

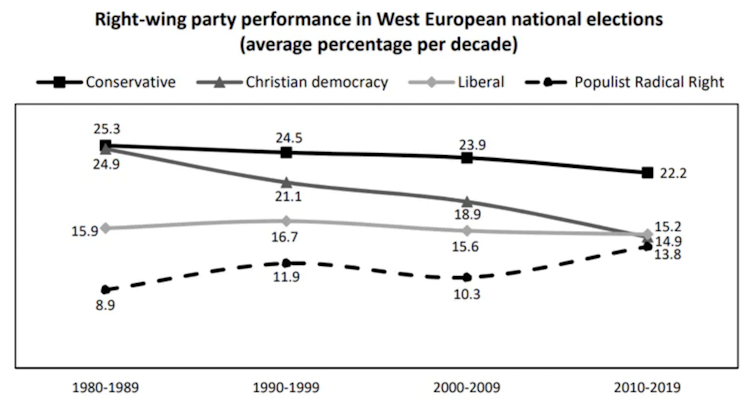

Looking at the trends for western Europe over the last four decades with this in mind, it’s clear that parties on the far right have become more popular over time, although not perhaps as much as some scare-story headlines are prone to suggest. Liberal parties have held fairly steady but it is the Christian democrats who’ve fared worst of all. As the chart shows, their performance across western Europe has declined more steadily than other conservatives since the 1980s.

The reasons for the trajectories of mainstream conservatives of all kinds are complex and obviously each country has its own story to tell. One cannot hope to appreciate the difficulties experienced by the mainstream right in Italy, for instance, without taking account of the post-cold war implosion of the country’s entire party system and the rise of Silvio Berlusconi’s hyper-personalist political outfits. Nor is it possible to understand the problems encountered by the Partido Popular in Spain without realising how big as issues that corruption and Catalan and Basque nationalism have each become.

However, as the research included in our new book shows, a useful way to frame the difficulties faced by the mainstream right more generally is to think of its members as facing two ongoing challenges.

One is the so-called silent revolution which, since the 1970s, has seen more and more people in Europe adopt what we might term cosmopolitan, progressive-individualist values. Their move away from the more traditional, and sometimes nationalistic and authoritarian, values associated (rightly or wrongly) with the right of the political spectrum has helped kickstart green and new left parties.

The other challenge is the so-called silent counter revolution: a backlash against that value-shift gathered pace in the 1990s and helped to fuel the rise of populist radical-right parties. Ever since, these have threatened to eat into the support of their more conventional counterparts on the right.

In fact, as the contributors to our book make clear, the mainstream right has indeed sometimes struggled to adapt – although some parties have coped better than others. But since their response has often involved adopting, over time, more socially liberal policies on issues like gender and sexuality while taking an increasingly nationalistic and restrictive stance on immigration, it is perhaps predictable that it is Europe’s Christian democratic parties (already coping with the decline of religious observance in a more secular world) which have struggled more than most.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel in Aachen, Germany, September 25, 2021. Photo: Reuters/Wolfgang Rattay

Survival at what price?

But if liberal and conservative parties haven’t generally run into quite so much trouble, might that have come at a heavy cost, both to their reputations and to the longer-term health of liberal democracy? To take just one example, the British Conservative party, in its desperation to see off Nigel Farage’s various vehicles, has adopted Europhobic and anti-immigration stances and seems determined to undermine the role of the judiciary and the independence of the Electoral Commission. Little wonder that some warn that it is going the way of Hungary and Poland.

That said, we need to be careful, as humans, not to over-interpret. And, recency bias aside, what’s just happened can sometimes still provide a useful reminder not to do so. In Austria, Sebastian Kurz – in some ways the poster boy for the idea that mainstream right parties can win by hugging the far right close – seems to have come unstuck, undone by allegations of corruption. Over the border in the Czech Republic, the mainstream right seems to have performed better than expected in their elections.

Finally, in Germany, as a flow-of-the-vote analysis shows, although the CDU/CSU did suffer net losses to the Greens, it may well have lost more voters to the grim reaper than it did to the far-right AfD, given that an estimated 7% of its voters have died since the last election. At least this time anyway, it was the good old fashioned SPD, rather than the products of the silent revolution and counter revolution, that did it by far the most damage.

Radical right-wing populism and social liberalism, then, remain a significant dual threat to Europe’s mainstream right, but they should still keep a weather eye on their traditional rivals too.![]()

Tim Bale, Professor of Politics, Queen Mary University of London and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Professor at the School of Political Science, Diego Portales University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.