The process of manufacturing post facto approval for the momentous changes that the Central government made to the status of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) in August 2019, with parliament’s nod, is in full swing.

Apart from the chest-thumping at the recent election rallies in Maharashtra and Haryana, and the latest round of military operations launched across the northwestern border, educational institutions are being pressed to organise debates on this issue.

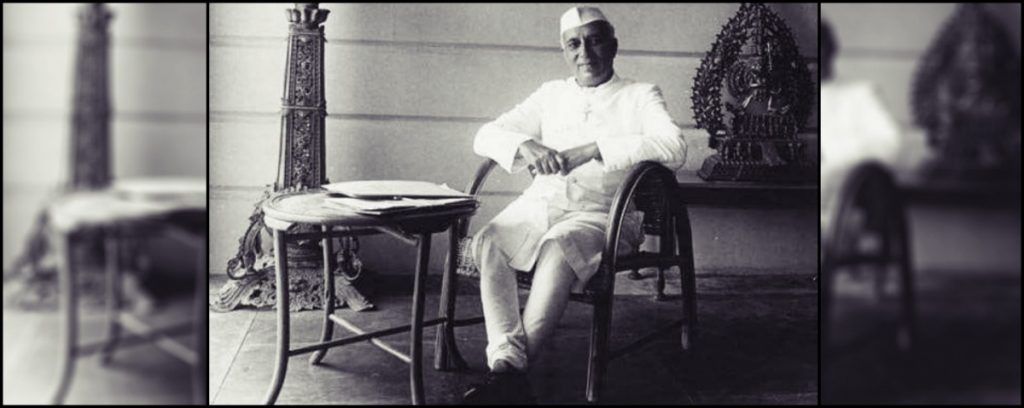

A common theme that pervades all these attempts to legitimise recent actions over J&K is the blame game targetting other political parties that governed the Centre and J&K for all that went wrong until August 2019. Arguably, the favourite whipping boy of critics of the Kashmir policy is Jawaharlal Nehru, who was the prime minister at the time of J&K’s accession to the Indian Union in October, 1947.

An oft-repeated charge against Nehru was that he did not show enough courage to beat back the invaders who descended on J&K in September 1947. Instead, he is accused of internationalising the matter by making a complaint to the United Nations at the end of December that year. So the picture fabricated for public consumption is one of contrast between the “weakness” of a “vacillating” leader in 1947 and the “aggressiveness” of his “decisive” successor in the 21st century. This is what current and successive generations are expected to lap up as the gospel truth about J&K affairs between 1947-48, as compared to the developments in the 21st century.

Also read: In Congressional Hearing, US Lawmakers Critical of India’s Actions in Kashmir

Unfortunately, in the 15th year of the implementation of The Right to Information Act, 2005 (RTI Act), crucial official papers that would help the citizenry, particularly millennials and their successors of Generation Z, and of course academia, to understand the Kashmir issue better, are being withheld on government orders.

The Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, popularly known as Teen Murti Library, under instructions from the Ministry of External Affairs, has denied me access to the files about J&K put together between 1947-49 by India’s second Army chief, Sir Roy Bucher.

The background

Readers might remember my piece published in The Wire in 2016 around the 68th anniversary of J&K’s accession to the Indian Union ( 26-27 October). I had published multi-colour scanned copies of the Instrument of Accession signed by the then Ruler of J&K, Maharaja Hari Singh and accepted by the then British Vice Roy in India, Lord Louis Mountbatten of Burma in 1947. The Wire resurrected that piece in the aftermath of the legislative exercise made in August 2019 to change J&K’s status in the Indian constitution.

In the interim, my ‘Quest for Transparency’ (a phrase borrowed from the website of the Prime Minister’s Office) continued, until it led me to a 20-odd-page transcript of an interview of Sir Francis Robert Roy Bucher, second commander-in-chief of the Indian Army (who took over from General Sir McGregor MacDonald Lockhart) conducted by noted biographer B.R. Nanda a few decades after the former’s retirement in October 1949.

The transcript of the interview with Bucher makes for very interesting reading, with tidbits about what happened in J&K narrated from memory and also his love for India and the respect he had for top leaders like Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Sir C. Rajagopalachari, the first governor general of independent India. This crucial interview contains multiple references to files and papers related to J&K affairs that were compiled between 1947 and October 1949 by Bucher and handed over to NMML.

Also read: To Be Indian in These Times Is to Battle a Crisis of Faith

When I looked up its index of archival papers, this file that Bucher had handed over to NMML was catalogued “closed”. Surprised that NMML would be holding back government records and papers from public scrutiny even after more than 70 years had lapsed, I inquired with some of the senior officials about this practice. One conceded that certain archival material is indeed withheld from scholars and researchers on two grounds:

- under instructions from the government department concerned; and

- under instructions from the donor or his/her family who hand over archival materials to NMML.

The RTI intervention

So at the beginning of this month (October 2019), I submitted a request under the RTI Act to NMML, through the RTI Online Facility, seeking the following information:

“1) A clear photocopy of any list of records, documents, papers, microfilms, microfiche and any other material available in the holdings of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library that are closed to the public, under instructions from any agency in or under the Government of India;

2) A clear photocopy of any list of records, documents, papers, microfilms, microfiche and any other material available in the holdings of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library that are closed to the public, under instructions from any agency in or under the State or Union Territory Governments;

3) The name of the agency which has issued instructions, the date of such instruction and the period for which every such record, document, paper, microfilm, microfiche or other materials referred to at para nos. 1 and 2 above, must remain closed to the public, and

4) Inspection for a period of 5 hours, the files and papers pertaining to Jammu and Kashmir handed over to the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library by General Sir Roy Bucher, 2nd Chief of the Army Staff of India, as mentioned in his interview with eminent historian Shri B. R. Nanda, which is recorded in the Sir Roy Bucher Transcripts available in your holdings.

Kindly make arrangements for supplying copies of all papers and micro-films or micro-fiche, if any, or any other materials that I may identify during the inspection.”

Also read: Authorities Refuse to Reveal Details of People From J&K Detained in UP Jails Under RTI

The PIO’s reply

The public information officer (PIO) was prompt enough to send a reply, free of charge, within 20 days of receiving the RTI application. He attached a list of archival papers that are closed for public scrutiny under orders from the Central government or under directions from the donor. A study of the list of “closed papers” attached to the PIO’s reply reveals the following interesting facts:

- Sir Roy Bucher’s papers (except for the transcript of the interview with B.R. Nanda) are closed under orders from the Union Ministry of External Affairs;

- Certain papers of Pyarelal, who was personal secretary to Mahatma Gandhi in his later years, and Sushila Nayyar, who was Gandhiji’s personal physician, are closed from public scrutiny under directions from Harsh Nayar. This restriction is to run for a period of 30 years. The start date of the embargo is not revealed in the RTI reply;

- Certain papers relating to former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi are closed under instructions from the Indira Gandhi Memorial Trust;

- Certain papers of Uma Shankar Dixit, former Union minister and governor of my home state, Karnataka during the 1970s (he was removed within a year and a half of appointment when the Janata government came to power in 1977) under instructions from his daughter-in-law Sheila Dixit, former chief minister of Delhi, who also passed away recently. Whether her heirs will continue to press for this secrecy remains to be seen;

- Certain papers of K. Hanumanthaiah, former chief minister of my home state Karnataka, (he was instrumental in completing the construction of Vidhana Soudha which houses the State Legislature and certain segments of the Government Secretariat) under instructions from one V. Shivalingam; and

- Certain papers donated by noted author Nayantara Sahgal who has instructed maintenance of secrecy until 2033. Incidentally, Sahgal is the niece of Nehru and the daughter of his sister Vijayalakshmi Pandit, who was India’s ambassador to the United Nations and the first woman president of the UN General Assembly in 1953.

The list that NMML’s PIO provided also includes papers of Gordon B. Halstead, who was associated with Gandhiji until the British government ordered him out in 1932 and those belonging to a former officer of the Indian Police Service, Ashwini Kumar. The PIO of NMML endorsed the note prepared by one Priyamvada, staffer of NMML, that Sir Roy Bucher’s papers and the rest listed above cannot be permitted for anybody to see or consult. Click here for the RTI application and reply.

What is problematic about the PIO’s reply

While there might be a justification for keeping personal papers of public figures donated to the NMML away from public scrutiny for a limited period or even eternally, every claim of secrecy for papers relating to official matters of the Central or state government must be tested on the touchstone of the RTI Act. Mere executive instructions issued by a babu are not adequate to prevent access to such records under the RTI Act.

Section 7(1) of the RTI Act clearly states that a request for information made under this law can be refused only on the basis of the exemptions listed under Sections 8 and 9. No other reason is valid. NMML is a public authority and its policies of allowing or refusing access to records relating to governmental affairs must be based on the standards and procedures of the RTI Act.

Also read: The Failing Art of Selling Normalcy in Kashmir

Refusal to provide access to Bucher’s papers related to J&K and other records relating to government affairs must be justified under the exemptions provided in the RTI Act, subject to the public interest override in Section 8(2) of the Act. This is the implication of the overriding effect that Section 22 gives the RTI Act over all other laws, rules, regulations or instruments that have the effect of a law.

MEA’s instructions alone, for maintaining confidentiality of these papers, cannot insulate Bucher’s J&K papers from public scrutiny. I will do the usual appeals in this case and report the developments to you in due course.

Nehru contemplated a strike on Pakistan to save J&K in 1947-48

Many writers and his bitterest critics have accused Nehru of not going the whole length of the way to take back the territory of J&K that had been seized by invaders with active support from across the border, in 1947, after it acceded to independent India soon after Dusshehra and Eid. Bucher seems to know otherwise. In his interview with B.R. Nanda, he remembers the tumultuous events as follows:

“…What went on within the Indian cabinet I do not know, but I have two letters at home [no I think they may even be in the file here (i.e. at NMML); anyway I have copies of them at home if they are not in the file] from Pandit Nehru; he had become very perturbed about the shelling of Akhnur and the Beripattan Bridge by Pakistan heavy artillery from just within Pakistan; he enjoined me to do all I could to counteract this. There was nothing which one could do except counter-shell.

In one his letters Panditji wrote: “I do not know what the United Nations” – I am quoting – “are going to propose. They may propose a ceasefire and what the conditions are going to be I do not know. If there isn’t going to be a cease-fire, then it seems to me that we may be faced with an advance into Pakistan and for that we must be prepared.” I assured my prime minister that all steps would be taken to meet any eventuality” (emphasis supplied).

Bucher continues the narrative saying a few days later then defence minister Sardar Baldev Singh telephoned him to announce a ceasefire. Bucher says he drafted the communication to his counterpart in Pakistan, General Gracey, about the ceasefire, showed it to Nehru in the Lok Sabha and signalled it to Pakistan to stop the hostilities. The justification for the ceasefire was made as follows:

“My Government (Indian Govt.) is of the opinion that senseless moves and counter-moves with loss of life and everything else were achieving nothing in Kashmir; that I (Sir Roy Bucher) had my Government’s authority to order Indian troops to cease firing as from a minute or so before midnight of 31st December…”

The transcript wrongly mentions 1948 as the year in which the ceasefire was signalled. In fact this action was taken at the stroke of midnight when the calendar changed from 1947 to 1948. Sadly, NMML does not permit copying of more than 20% of these old transcripts. So I had to pick and choose from the 20-odd page long document, extracts that serve the purpose of this article. Click here for extracts from the transcript of Bucher’s interview with Nanda.

In order to get to the bottom of the truth, the Sir Roy Bucher files and all other related papers, transcripts and microfilms in the NMML holdings as well as archival materials held in the National Archives (from where I obtained a scanned copy of J&K’s Instrument of Accession) and the MHA and MEA must be made public without any delay.

Also read: The Siege in Kashmir Is Damaging India’s Image Abroad

Very few members of the generation that witnessed the developments in J&K in 1947 are still with us today and their narratives of the developments that led to J&K’s accession to India are at variance with each other on some crucial issues. Transparency of contemporary official records is indispensable to counter propagandist versions of contemporary history.

The NDA-II government promised to declassify papers held in secret for several decades about Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. It is yet to fully deliver on this commitment. Whether NDA-III will go the whole length of the way to make archival papers about J&K public remains to be seen.

I must also clarify, I hold no brief for any individual. It is important to unearth facts and details from locked-up files and papers to reconstruct a truer picture of what happened in government circles in 1947-48. I hope the RTI Act will prove a useful tool to bring in greater transparency about that sanguinary episode of modern Indian history, if the government does not volunteer to open up these papers for public scrutiny.

Venkatesh Nayak is programme head of the Access to Information Programme of the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative.