A disingenuous narrative is being woven around the close contest in Madhya Pradesh. That the state has not rejected outgoing chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan and, despite a setback to the BJP, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s popularity is intact in the state.

The narrative is inspired by two facts. One, the Congress, though the single largest party, has polled 37,000 less votes than the BJP. Two, the seat difference between the winner (114) and the loser (109) is just five in the 230-strong assembly. Both the rivals have garnered 41% votes each, with a marginal difference of 0.1%. Based on the vote share, the BJP stands to lose 18 out of 29 Lok Sabha seats, if the election were held today.

Also Read: If Congress, BSP Had Allied in Madhya Pradesh, the Map Would Look Radically Different

Put in perspective, the narrative’s hollowness becomes evident. The Congress’s tally improved by 56 seats, from 58 to 114, and increased its vote share by 4%. This is no mean achievement, given the fact that the BJP pulled all stops to retain power. In terms of organisation and resources, the Congress was simply no match to the well-oiled election-fighting machine of the rival, which was in power in Madhya Pradesh for 15 years. Had it not been for quite an unexpected setback to it in the Vindhya region, the Congress tally could well have crossed the 125 mark.

In all regions across urban-rural divide, the Congress surged head of the BJP. In Malwa-Nimad (66) Congress seats rose from 11 to 35, in Gwalior-Chambal (34) from 12 to 19, in Mahakoshal (38) 13 to 21, in Madhya Bharat (36) six to 13 and in Bundelkhand (26) from ten to 16. But in the Vindhya region (30), the Congress shrunk to six from ten. Thus, the Congress, overall wrested 60 seats from the BJP in other regions and conceded four in the Vindhya.

A fairly uniform rise of the Congress across the regions, except Vindhya, could not have been possible without a dent in popularity for the ruling party. That said, it was still possible for Chouhan to somehow scrape through with a vastly reduced margin for a record fourth time. But the double whammy of demonetisation – which angered the farmer – and the Goods and Service Tax (GST) – which hit the trader – shattered the Chouhan’s hopes to retain power. Therefore, a disappointed Chouhan can justifiably blame his defeat on Modi whom he, otherwise, called “god’s gift to India.”

A farmer’s protest in Madhya Pradesh. Credit: Reuters

Narendra Modi’s policies

All the woes that befell the ousted Chouhan government had their genesis in the Modi government’s disastrous policy decisions. Madhya Pradesh was no stranger to agrarian crisis, but it was aggravated only after farmers ran out of cash due to demonetisation two years ago.

Petty traders had had little problems with their favourite party, the BJP, till the GST’s shoddy implementation broke the back of their business. Upper castes, which have been traditional BJP supporters, may have remained loyal to the party had it not been for the confusing signals emanating from the Sangh parivar over the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. Constitutional amendment to the Act by the NDA government in August spawned numerous anti-reservationist outfits in MP which exacerbated societal discord.

His [Narendra Modi’s] ten rallies across the state in the run up to the election evoked more sarcasm than cheers.

As if his policies were not enough to fuel popular anger against the state government, the prime minister’s acerbic speeches in the state targeting Congress president Rahul Gandhi further queered the pitch for his party’s prospects. His ten rallies across the state in the run up to the election evoked more sarcasm than cheers.

BJP president Amit Shah’s introduction of micromanagement of electioneering and overdependence on his own team members antagonised the state’s devoted party workers, who were accustomed to indigenous way of door-to-door campaigning.

Also Read: Seven Big Takeaways from the Assembly Elections Results

Uttar Pradesh chief minister Adityanath sought to whip up communal passion to polarise the campaign on the Hindu-Muslim line. But, unlike UP, 91% of the Hindus in Madhya Pradesh were not impressed with Adityanath’s implicit message that they should be unduly worried about the presence of 8% Muslims in the state. His ‘Ali versus Bajrang Bali‘ exhortation had no takers in the state beyond, of course, the rabid Hindu fundamentalists.

A majority of journalists, who extensively covered campaigning in Madhya Pradesh, concurred with the perception that had it not been for the cumulative effect of demonetisation and the GST, the BJP had the chance to rule the state for a record fourth consecutive time. Chouhan put in valiant efforts to shore up the damage caused to the party’s prospects.

By the time the BJP’s top leaders started carpet bombing ahead of the election, the party’s chickens were as good as cooked.

The script for the BJP’s poor show had begun to be written over the last couple of years.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi introduces the BJP candidates for Madhya Pradesh assembly elections during a public meeting. Credit: PTI

Chouhan’s own plight

Chouhan’s own plight aptly reflected his party’s vulnerabilities. Like the 2008 and 2013 assembly elections, he was the pivot around whom the electioneering revolved in the state. The BJP put all its eggs in his basket, and the Congress targeted Chouhan more than his party. However, unlike the previous polls, Chouhan didn’t look like the knight in the shining armour, with his juggernaut rolling thunderously across MP.

Chinks in the armour became more visible as the campaigning started to peak. What was unthinkable in the past became apparent this time: a beleaguered Chouhan. He faced former MPPCC president Arun Yadav in the Budni constituency where he had sailed through breezily four times in the past (1990, 2006, 2008 and 2013).

He was booed by the public during his Jan Ashirvad Yatra at many places; a slipper was hurled at him in a town; he abruptly aborted the yatra owing to poor public response; his brother-in-law, Sanjay Singh Masani, defected from the BJP to the Congress; his wife Sadhna Singh got an earful on two occasions from angry women while campaigning in her husband’s constituency.

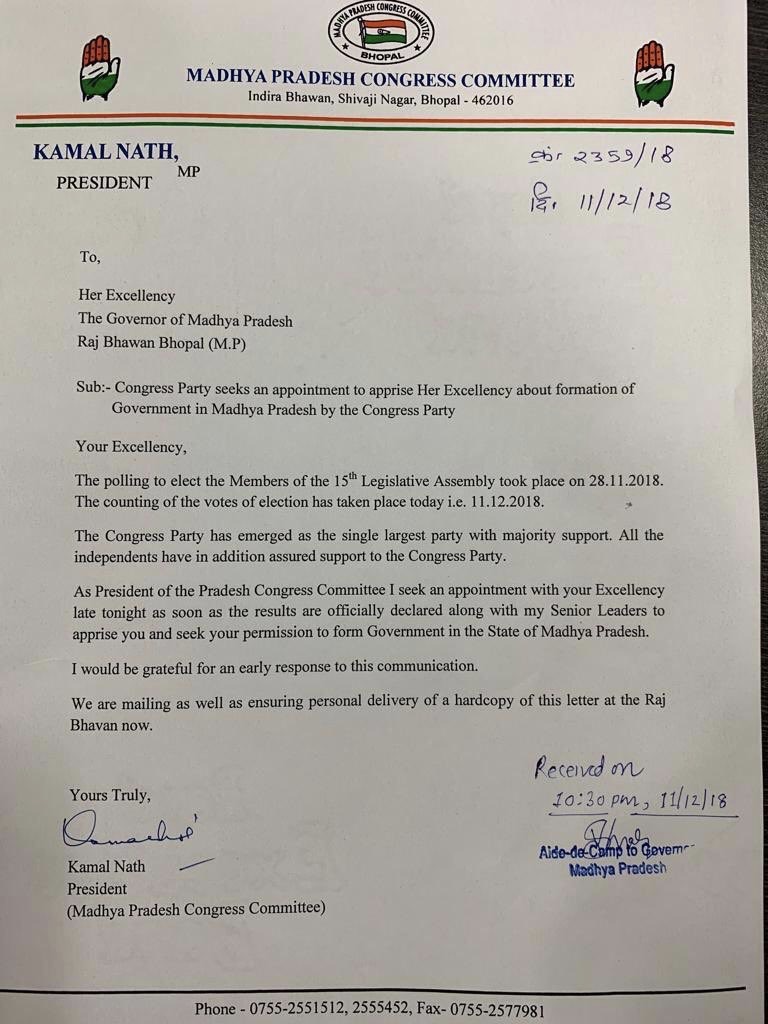

Also Read: In Late-Night Move, Congress Stakes Claim to Form Government in MP

All these developments clearly indicated that Chouhan minister was battling severe anti-incumbency. He had been ruling the state since 2005, unencumbered of any visible dissent within the ruling party. In the 13 years as chief minister, Chouhan had seen to it that none within the party rose high enough to pose a challenge to his leadership. Therefore, the task of salvaging the government a fourth time from the quagmire of public resentment squarely lies on his shoulders. And opinion polls suggested he might not rise equal to the task.

Doubts about the Chouhan’s chances of retaining power stemmed from many factors. For one, a resurgent Congress under Kamal Nath’s leadership looked far more united and determined for the first time since the party was routed in 2003. People didn’t seem willing to be swayed by either communal or casteist electoral ploys.

More importantly, the BJP’s rebels queered the pitch for nearly two dozen official candidates. That was a clear indication that the chief minister’s writ didn’t run in the party any more. In the previous elections, just calls from Chouhan were enough for rebel candidates to withdraw nominations.

Madhya Pradesh chief minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan. Credit: Facebook/Shivraj Singh Chouhan

The Congress’s resurrection

One leader’s imposing presence in the Madhya Pradesh election scenario upset all the BJP’s calculations in the run up to the polling, and his name is Kamal Nath. His organisational capacity, clout with the party high command and ability to ensure a facade of unity among top party leaders inspired belief among the Congress’s rank and file that this election is pretty well winnable. To the delight of the Congress workers, Kamal Nath outsmarted the combined political acumen of the BJP leadership, be it stealing the march over Hindutva, candidate selection or poaching dissidents from the opposition camp.

A comparative journey of both the major rivals, the Congress and the BJP, over the last few months provides a useful insight into the changing election scenario.

However, anti-incumbency against his government had begun to be visible in the past two years.

The Vyapam scam was huge, though not-so-visible: the albatross around Chouhan’s neck since the multi-billion job-cum-admission swindle surfaced in 2013. However, anti-incumbency against his government had begun to be visible in the past two years. It was manifest in the upper castes’ simmering anger over the Chouhan’s rather unwise ‘Mai ka lal‘ rhetorical remark in a meeting of the SC/ST government employees in 2016.

Chouhan said in the meeting that, “Koi mai ka lal arakshan khatm nahikKar sakta jab tak mai chief minister hun” (No one can scrap reservation till I am the chief minister). This caused a wave of anger among the BJP’s upper caste vote bank. Sensing this, Chouhan undertook a political pilgrimage of the Narmada, which connected him to 144 constituencies along the holy river.

Agrarian distress and farmers’s anger

However, the extravagant journey proved counterproductive. While he was away from Bhopal, agrarian crisis was brewing in the state. It erupted suddenly in June last year. The farmers hit the streets to demand remunerative price for their produce, among other things. The police resorted to force to quell the agitating farmers. In Mandsaur, six farmers were killed on June 5, 2017.

Since then, Chouhan’s popularity graph plummeted drastically. All moves to placate the farmers in the aftermath of the bloodied stir bred more skepticism. No amount of sops offered to the farmers could restore their trust in the BJP government.

By September, the trio of Kamal Nath, Digvijay Singh and Jyotiraditya Scindia managed to quell the doubts to a large extent.

However, while anger against the government was mounting, the Congress was not viewed as a viable alternative. Chouhan still had the benefit of the TINA (There Is No Alternative) factor.

Popular perception about the Congress began to change after Kamal Nath took over as the PCC chief. He infused fresh energy into the organisation. However, doubts about the Congress’s ability to oust the BJP still persisted.

By September, the trio of Kamal Nath, Digvijay Singh and Jyotiraditya Scindia managed to quell the doubts to a large extent. They undertook different responsibilities, but worked in tandem. Kamal Nath took up the task of reviving the organisation, Digvijay leveraged his pan-Madhya Pradesh image to galvanise idle workers and Scindia cast his charm offensive through public rallies. Their combined efforts bore fruits.

Madhya Pradesh state Congress committee chief Kamal Nath with Jyotiraditya Scindia and Digvijay Singh. Credit: PTI

The Congress tactfully negotiated the anti-reservation protests that had threatened to spawn caste conflict in the state. The BJP government failed miserably on this count. The soft versus hard Hindutva narrative built in the media following the Congress’s announcement to open cowsheds in all village panchayats and construct the mythical path traversed by Rama during his exile gave jitters to the BJP. Congress president Rahul Gandhi’s temple-hopping in Madhya Pradesh further upset the ruling party.

Before the BJP could unleash its brand of Hindutva to counter the Congress, Kamal Nath switched gears. He launched a 40-question series to discomfit the chief minister. The BJP government chose to ignore the uncomfortable questions on its performance on a range of issues. It was again advantage Congress.

The real acid test for the Congress was to avert insidious rebellion, which is a bane of the party, following declaration of candidates. On this count too, the Congress was seen to have fared better than the BJP.

Rakesh Dixit is a Bhopal-based journalist.