When the Black Death swept across Asia and Europe in the 1340s, the upheaval was extraordinary. Up to half the population of Europe died over the course of four years, and bubonic plague continued to wrack the globe in the centuries that followed. The fear and confusion felt by communities prompted a range of reactions, and forced governments to take drastic measures in a bid to control the disease.

Some responses to the epidemics were pragmatic, others heartbreakingly inhumane. What is striking, though, is that as the globe faces a new pandemic in COVID-19, some of our actions are eerily similar to those of our ancestors.

Since the outbreak of coronavirus, there have been rumours of people intentionally spreading the disease. Some of these reports appear to be true: for example, several people in Britain have been arrested for maliciously coughing on others, especially the old and vulnerable.

Also read: Watch | Northeast Indians Say #StopRacism

Confirmed cases like these have given way to other rumours, including that post workers and delivery drivers have been intentionally spitting on packages to spread the virus. Many, if not all, have since turned out to be fake, but that hasn’t stopped these tales spreading across the world like wildfire.

Though unnerving, fear of people maliciously spreading disease is not new. During a bout of plague in 16th-century Geneva, a rumour broke out that house-clearers and carers were trying to spread plague through the city. The method was different to now – and more disturbing. They were thought to be smearing the fat of plague victims over doorknockers and handles, hoping that homeowners would get infected as they entered and left.

There were two theories behind why anyone would do this. Some worried that carers resented putting their lives at risk – others were paranoid that workers were profiteering from the infection, by raiding the victims’ houses after they died.

Publishing death tolls

The news cycle has rarely headlined anything but COVID-19 since it was declared a pandemic. A morbid fascination has developed around the rate of infection: Johns Hopkins University is keeping a tally of global infections, and the BBC has launched an interactive page where people can check infections in their area.

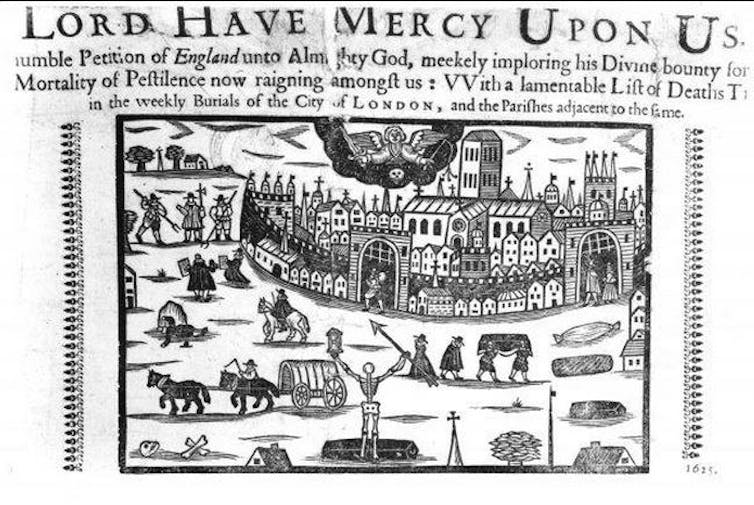

These are strikingly similar to a popular broadsheet that circulated across England’s capital in 1665. Alongside documenting previous bouts of plague, Lord Have Mercy broadsheets supplied up-to-date figures of London’s running death toll for the year, and what proportion had died of plague. They sometimes even showed the number of deaths in each parish.

Broadsheets were published weekly recording death tolls in London. Vanderbilt University

Besides demonstrating an all-absorbing fascination with epidemics, these broadsheets had a practical function. They helped gauge how virulent the outbreak was compared to previous ones, and could also act as a guide on which parts of the city to avoid. The Lord Have Mercies also tried to be helpful (and drive up sales) by publishing home remedies to help protect from the disease: some of which are still doing the rounds today. One iteration offered “A cheap Medicine to keep from infection”:

Take a pint of new Milk, and cut two cloves of Garlick very small, put it in the milk, and drink it mornings fasting [(or breakfast], and it preserveth from infection.

Similar advice on the immune-boosting properties of garlic is being shared across social media platforms and health forums as we speak.

Blaming minorities

Acute stress can sometimes bring out the worst in humanity. Fear and panic brings pre-existing suspicions and vendettas to the surface, and can eventually boil over in devastating ways. Historically, plague outbreaks marked a spike in persecutions of already vulnerable and marginalised communities.

A frequent rumour across medieval and early modern Europe was that Jewish communities – already shunned in most Christian states – were to blame for plague, prompting mass arrests and executions. There was no evidence to support this theory – all confessions were given under torture – but scapegoating minorities continued throughout the period. Expelling Jews and other marginalised groups such as beggars and prostitutes from towns became common, making the most vulnerable even more so.

Also read: Pandemic vs Prejudice

Unfortunately, we are seeing history repeat itself during the coronavirus pandemic. There have been reports of racially motivated attacks in the UK and across the world, particularly targeting people with an “Asian appearance”, due to the origin point of COVID-19 in Hubei province in China.

Everyday heroism

Despite the panic, some of the best in humanity is shining through, too. Like the Peak District village which chose to shut itself off from the wider world to stop plague spreading in 1665, an Italian village is now in full quarantine and acting as a “human laboratory” for scientists to understand the coronavirus.

Also read: Khidmat-e-Khalq: Young Volunteers Team Up to Help Those in Need

In the past, neighbours would drop food through the windows of quarantined houses and many doctors, priests and gravediggers risked their lives to deliver essential services. Today, the same selfless attitude can be seen in the community groups appearing across the world an organising via social media as well as and national services working round the clock to save lives.

As history repeats itself through this new pandemic, there are some important lessons we can learn from the past.![]()

Tabitha Stanmore is honorary research fellow in early modern studies at department of history, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Featured image credit: Reuters

![]()