Grey’s Anatomy, the longest running prime-time medical drama on US television, contains many scenes of doctors and nurses in full gear (hospital scrubs, surgical caps, face masks) around the operating table. As they talk, laugh and argue, close-ups of the actors’ eyes convey concentration and emotion.

These scenes contradict one of the common arguments against face coverings — or more accurately, niqabs worn by some Muslim women — that they are a barrier to communication.

Now that face masks are being used to help fight against the spread of COVID-19, it has caused some to look anew at general discrimination against Muslim women wearing niqabs. And it has got me wondering about Québec’s face-covering ban, which came into law in October 2017 as well as France’s ban which came into law in 2011.

If Canadians, Americans and Europeans can get used to the new ubiquitous face masks, will they also get used to niqabs? Will discrimination against the few women in the West who wear it stop?

History of face politics

The European disapproval of the face veil has a long history, as I learned while researching for my book on Canadian Muslim women and the veil.

Niqab has been seen as both a symbol of cultural threat and also of the silencing of Muslim women. In her book, Western Representations of the Muslim Woman, Moja Kahf traces one of the first discussions of the veil in western fiction to the novel Don Quixote. One of the novel’s characters, Dorotea, asks about a veiled woman who walks into an inn: “Is this lady a Christian or a Moor?” The answer came: “Her dress and her silence make us think she is what we hope she is not.” As this scene from Don Quixote indicates, European women sometimes also covered their faces or hair but when they did so, it was not associated with something negative.

Eventually, the rise of western liberalism, with its prioritisation of the individual, capitalism and consumerism led to a new “face politics.” Jenny Edkins, professor of politics at the University of Manchester, studied the rise of a politics centred around this new meaning of the “face,” including the idea that the face “if it can be ‘read’ correctly, may be seen to display the essential nature of the person within.”

Also read: I Was Asked to Remove My Hijab to Appear For the NEET Exam

The flip side of this new face politics became true as well: concealing the face became something suspicious, as if the person had something they wanted to hide, and prevent others from knowing the real them.

At the same time, we grow up learning our face is something to be manipulated, in the same way actors manipulate their faces to entertain viewers. We learn about “putting on one’s face” with makeup; “facing the world” through our education and personal grit; cultivating “poker face” to deceive people in cards or lying to parents and teachers. We learn how to compose our face so as not to show emotion in the wrong places, like crying at work.

The face is often a mask of our real selves.

Anti-niqab attitudes and hate crimes

Generally, hate crimes are on the rise in Canada with the highest increases in Ontario and Québec. In Ontario, the increase was tied to hate crimes against Muslims, Black and Jewish populations. In Québec, the increase was the result of crimes against Muslims. According to a recent peer-reviewed study by Sidrah Ahmad, a PhD student at the University of Toronto, a tally of hate crimes in Canada released by Statistics Canada in 2015 noted that Muslim populations had the highest percentage of hate crime victims who were female.

Also read: The Hijab Has Arrived: Identity in the Time of Dissent and Conditional Allies

The rise in hate crimes mirrors the opinion of many public leaders who have loudly proclaimed their anti-niqab attitudes. Jason Kenney, the former Canadian Minister of Citizenship, Immigration and Multiculturalism, tried — and failed — to ban niqab in citizenship ceremonies. In 2015 he called the niqab “a tribal cultural practice where women are treated like property and not like human beings.” In the same year, former Prime Minister Stephen Harper called it a dress “rooted in a culture that is anti-women … [and] offensive that someone would hide their identity.”

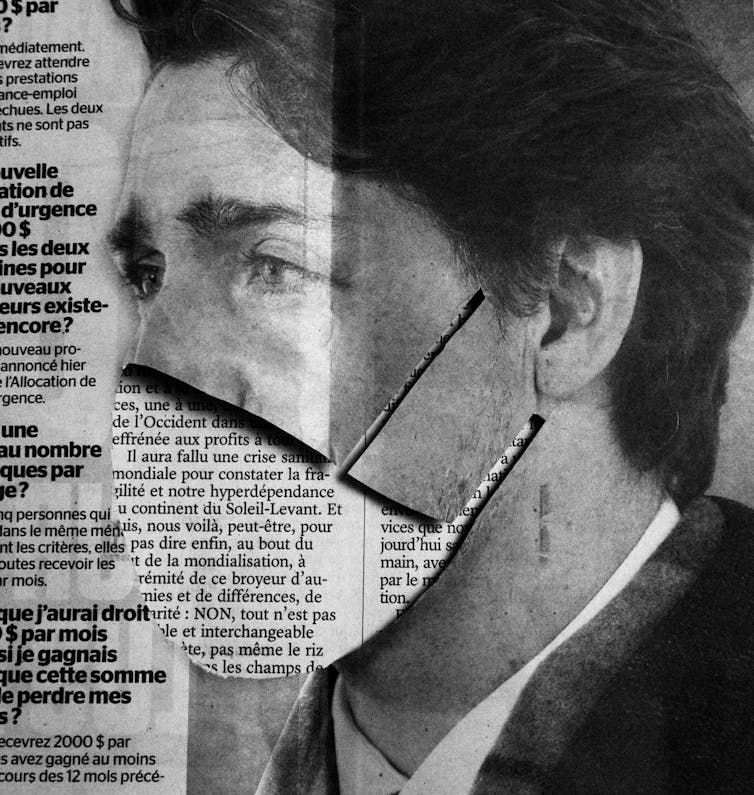

Polls on attitudes about the niqab have found people have grown increasingly opposed to its presence in Canadian society. Photo: Charles Deluvio/Unsplash.

A 2018 Angus Reid poll found that the majority of Canadians support a ban of niqabs on public employees. These contemporary attempts to unveil Muslim women echo British and French attempts to the same in both colonial and current times.

Medical face veils

In a recent op-ed for the Toronto Star, University of Windsor law student Tasha Stansbury pointed out that in Montréal hospitals, people are being asked to wear surgical masks. They walk in and interact with medical staff without being asked to remove their mask for identity or security purposes.

But a woman wearing a niqab walking into the same hospital would be forced by law to remove it.

A decade ago, US philosophy professor Martha Nussbaum brilliantly exposed the hypocrisy of face veil bans, in an opinion piece for the New York Times. If it is security, she asked, why can we walk into a public building bundled up against the cold with our faces covered in scarves? Why are woolly scarves not seen to hamper reciprocity and good communication between citizens in liberal democracies? She wrote:

“Moreover, many beloved, trusted professionals cover their faces all year round: surgeons, dentists, (American) football players, skiers and skaters … what inspires fear and mistrust in Europe … is not covering per se, but Muslim covering.”

A New York City police officer wears a patriotic face mask. Photo: Julian Aan/Unsplash.

Is a face mask used to help block coronavirus really that different from a niqab?

Both are garments worn for a specific purpose, in a specific place and for a specific time only. It is not worn 24/7. Once the purpose is over, the mask and niqab come off.

The calling of the sacred motivates some to wear the niqab. A highly infectious disease propels many to wear face masks.

If we all start wearing masks does it mean we have succumbed to a form of oppression? Are we submissive? Does it mean we cannot communicate with each other? If we are in Québec, will we be denied employment at a daycare? Refused a government service? Not allowed on the bus?![]()

Katherine Bullock is lecturer in Islamic Politics, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()