The fossil-fuel industry is lawyering up.

To date, nine cities have sued the fossil industry for climate damages. California fisherman are going after oil companies for their role in warming the Pacific Ocean, a process that soaks the Dungeness crabs they harvest with a dangerous neurotoxin. Former acting New York state attorney general Barbara Underwood has opened an investigation into whether ExxonMobil has misled its shareholders about the risks it faces from climate change, a push current attorney general Leticia James has said she is eager to keep up.

Massachusetts attorney general Maura Healey opened an earlier investigation into whether Exxon defrauded the public by spreading disinformation about climate change, which various courts – including the Supreme Court – have refused to block despite the company’s pleas.

And in Juliana vs. US, young people have filed a suit against the government for violating their constitutional rights by pursuing policies that intensify global warming, hitting the dense ties between big oil and the state.

These are welcome attempts to hold the industry responsible for its role in warming our earth. It’s time, however, to take this series of legal proceedings to the next level: we should try fossil-fuel executives for crimes against humanity.

Guilty beyond a reasonable doubt

Just one hundred fossil fuel producers – including privately held and state-owned companies – have been responsible for 71% of the greenhouse gas emissions released since 1988, emissions that have already killed at least tens of thousands of people through climate-fueled disasters worldwide.

The Green New Deal advocates have been right to focus on the myriad ways that decarbonisation can improve the lives of working-class Americans. But an important complement to that is holding those most responsible for the crisis fully accountable. It’s the right thing to do, and it makes clear to fossil-fuel executives that they could face consequences beyond vanishing profits.

More immediately, a push to try fossil-fuel executives for crimes against humanity could channel some much-needed populist rage at the climate’s 1%, and render them persona non grata in respectable society – let alone Congress or the UN, where they today enjoy broad access. Making people like Exxon CEO Darren Woods or Shell CEO Ben van Beurden well known and widely reviled would put names and faces to a problem too often discussed in the abstract. The climate fight has clear villains. It’s long past time to name and shame them.

Left unchecked, the death toll of climate change could easily creep up into the hundreds of millions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in turn unleashing chaos and suffering that’s simply impossible to project. An independent report commissioned by 20 governments in 2012 found that climate impacts are already causing an estimated 400,000 deaths per year.

Also Read: Moving Away From Fossil Fuels Isn’t Separate From Moving Towards Social Justice

Counting a wider range of casualties attributed to burning fossil fuels – air pollution, indoor smoke, occupational hazards, and skin cancer – that figure jumps to nearly 5 million a year. By 2030, annual climate and carbon-related deaths are expected to reach nearly 6 million. That’s the rough equivalent of one Holocaust every year, which in just a few short years could surpass the total number of people killed in World War II. All caused by the fossil-fuel industry.

Knowing full well the deadly consequences of continued drilling, the individuals at the helm of fossil-fuel companies each day choose to seek out new reserves to burn as quickly as possible to keep their shareholders happy. They use every possible tool – and they have many – to sabotage regulatory action.

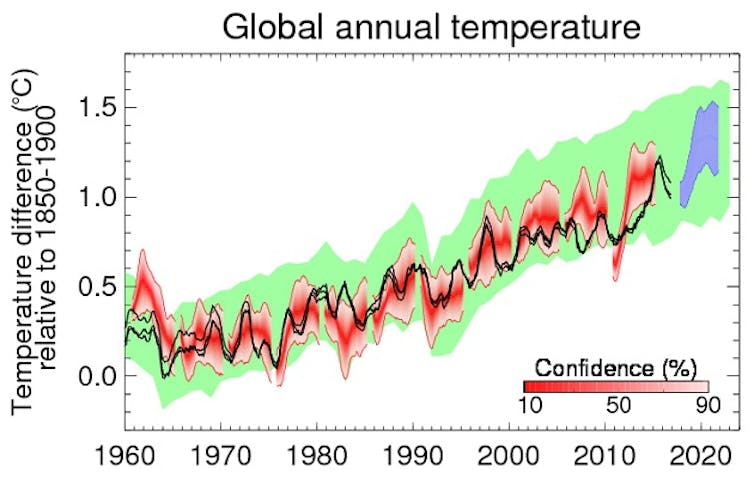

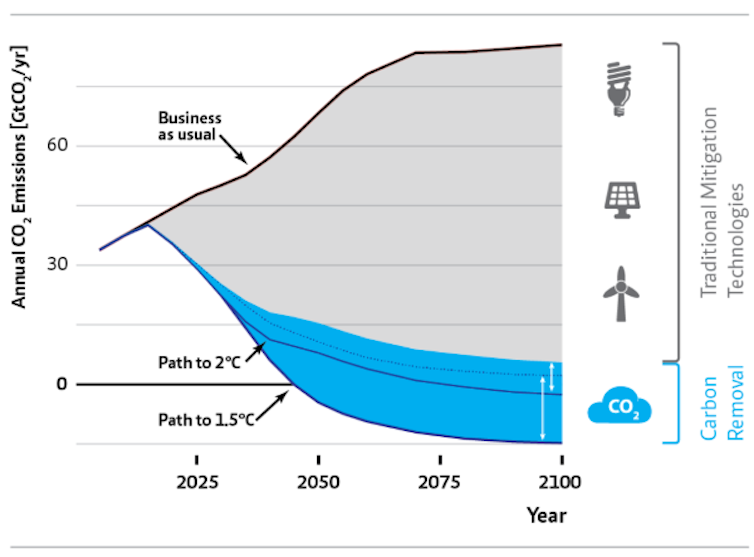

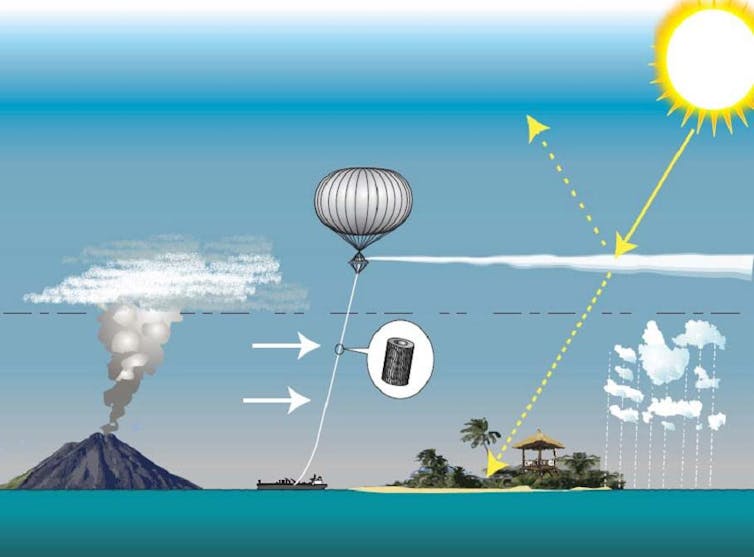

That we need to instead strip fossil fuels from the global economy isn’t up for debate. Without the increasingly distant-seeming deployment of speculative, so-called negative emissions technologies, coal usage will have to decline by 97%, oil by 87%, and gas by 74% by 2050 for us to have a halfway decent shot at keeping warming below 1.5 degrees celsius. That’s what it will take to avert pervasive, catastrophic climate impacts that will destabilise the very foundations of society. (Keeping warming to a more dangerous 2.0 degrees celsius will require decarbonisation that’s almost as abrupt.)

A recent report by Oil Change International detailing the climate costs of continued drilling lays the problem out in simple terms: either we embark on a managed decline of the fossil-fuel industry, or we face economic and ecological ruin. Simply put, the business model of the fossil-fuel industry is incompatible with the continued existence of anything we might recognise as human civilisation.

Barring a major course correction, that business model – and more specifically, the executives who have designed and executed it – will be responsible for untold suffering within many of our lifetimes, with the youngest and poorest among us bearing a disproportionate burden, along with people of color and residents of the Global South.

As recent research and reporting have documented, some of the world’s biggest polluters have known for decades about the deadly threat of global warming and the role their products play in fueling it. Some companies began research into climate change as early as the 1950s. These days, none can claim not to know the mortal danger posed by their ongoing extraction.

The logo of Exxon Mobil Corporation is shown on a monitor above the floor of the New York Stock Exchange in New York, December 30, 2015. Credits: Reuters/Lucas Jackson/File Photo

Literally a crime against humanity

Technically speaking, what fossil-fuel companies do isn’t genocide. Low-lying islands and communities around the world are and will continue to be the worst hit by climate impacts.

Still, the case against the fossil-fuel industry is not that their executives are targeting specific “national, ethnical, racial, or religious” groups for annihilation, per the Rome Statute, which enumerates the various types of human rights abuses that can be heard before the International Criminal Court. Rather, the fossil industry’s behavior constitutes a Crime Against Humanity in the classical sense: “a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack,” including murder and extermination. Unlike genocide, the UN clarifies, in the case of crimes against humanity, it is not necessary to prove that there is an overall specific intent. It suffices for there to be a simple intent to commit any of the acts listed. The perpetrator must also act with knowledge of the attack against the civilian population and that his/her action is part of that attack.

Fossil-fuel executives may not have intended to destroy the world as we know it. And climate change may not look like the kinds of attacks we’re used to. But they’ve known what their industry is doing to the planet for a long time, and the effects are likely to be still more brutal if the causes are allowed to continue.

The evidence stacks up

In September 2015 InsideClimate News broke the story that Exxon scientists first started looking into climate change in the mid-1970s. It didn’t take them long to find out both that it was a real problem and that their bread and butter was a chief cause. When the rest of the US learned of these dangers – thanks in part to James Hansen’s testimony before Congress in 1988 – Exxon and friends began pouring millions of dollars into elaborate disinformation campaigns casting doubt on findings their own scientists had validated.

Dutch journalist Jelmer Mommers has unearthed many incriminating documents about similar actions taken by Shell, including a 1988 report showing that their executives were fully aware of the danger that climate change posed and the company’s own role in it.

The report’s authors found that their own products accounted for an estimated 4% of the world’s carbon emissions in 1984. “With very long time scales involved,” company scientists recommended, “it would be tempting for society to wait until then to begin doing anything. The potential implications for the world are, however, so large, that policy options need to be considered much earlier. And the energy industry needs to consider how it should play its part.” In response to the documents revealed in Mommers’s article, Friends of the Earth Netherlands has announced it will bring a suit against Shell to rapidly begin winding down its oil and gas production.

Industry-funded disinformation campaigns would shape the US’s national conversation on climate politics for the decades after Hansen’s testimony, and still do. But sensing a change in the political weather, fossil-fuel companies have taken on a new double identity. With one hand – or maybe just a few fingers – they espouse their commitment to climate action and even documents like the Paris Agreement. With the other they continually hunt for new markets and planet-wrecking reserves, sending legions of lobbyists into Washington to beef up subsidies and tear up regulations, and fighting even modest policies to rein in their actions.

Despite clear culpability, the industry’s attempts to present itself as a good-faith actor in the climate fight are largely succeeding. Industry shills stalk the halls of the UN’s annual climate talks, appearing at side events alongside respected environmental NGOs and UNFCCC officials, and chatting freely with national delegations.

At COP 24 last year in Poland, GasNaturally co-hosted a cocktail hour with the European Union, and Shell bragged about its influence in grafting a whole section onto the Paris Agreement. The Polish coal sector was a main sponsor of the whole event.

Also Read: COP24 Summit Shows Global Warming Treaties Can Survive Anti-Climate ‘Strongmen’

Stateside, advocates of certain forms of carbon pricing – like one plan drafted up by former Bush and Reagan cabinet officials – have boasted of garnering support and funding from the likes of Exxon and BP, apparently a marker of their respectability. When one such policy actually came up for a vote in Washington State last year, though, BP and other oil producers spent tens of millions of dollars to crush it. We’ve let them get away with it for too long.

The Nuremberg Precedent

Let’s call this what it is: an atmosphere of impunity for atrocity. At the very least, the fossil-fuel industry should be barred from international climate negotiations and any national-level climate policy making discussions, just like the tobacco industry and its emissaries are barred from World Health Organisation talks. In the US, that ban should include the congress people on both sides of the aisle that the industry deputises to act on their behalf with hefty campaign contributions. There were more than a few good reasons, after all, that the Allies didn’t invite Hitler to weigh in on their strategy for crushing the Nazis.

After the war, though, the ensuing Nuremberg Trials of Nazi war criminals wrote an important precedent into international law, establishing that “crimes against international law are committed by men, not by abstract entities, and only by punishing individuals who commit such crimes can the provisions of international law be enforced.” At that point, there was no legal framework to understand violence on the scale of those that Hitler’s regime had just carried out, let alone to punish it. To remedy that the international community came together to create and implement one.

On climate, the precedent set in Nuremberg offers other lessons as well. It’s hard to think of a problem more widely attributed to “abstract entities” than global warming, allegedly the product of some unquenchable, ubiquitous human thirst for new stuff. That old Pogo cartoon still holds sway in the popular imagination: “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

There’s some truth to that – we do all create demand for fossil fuels, after all. But supply creates demand. And while free market dogmatists may think otherwise, there’s no reason why the popularity of a product means it should exist in perpetuity when the risks are so colossal and there are alternatives at the ready.

One of the best parallels for trying corporate executives for crimes against humanity might be the so-called IG Farben Trials, in which executives of the IG Farben Company – which worked with the Nazis to produce Zyklon B gas, a pesticide used extensively to kill Jews in the Holocaust – were tried before US Military Courts in Nuremberg. The company also developed several processes that aided in the Nazi war effort, like synthesizing rubber and oil out of coal. They employed slave labour provided by the Nazis, even constructing a factory just outside of Auschwitz so they could put prisoners to work.

Farben executives and plant managers were tried on these and other charges. Just thirteen of the twenty-four indicted were found guilty, and the longest sentence anyone of them served was eight years, including time served. After prison, several went on to lucrative consulting gigs and board positions for German chemicals companies, including former subsidiaries of the now-disbanded IG Farben, and companies like Dow Chemical. After serving his four-year prison term for the “plundering and spoliation of occupied territories,” IG Farben CEO Hermann Schmitz went on to take a senior post at Deutsche Bank.

The head of the company that would become the war’s largest distributor of Zyklon-B – Bruno Tesch – fared less well. He was tried separately before a British military tribunal and executed, alongside his second-in-command. Court documents detailed precisely how much money he and his main business partners had made from selling the agent to the Nazis.

Defendants in the dock at the Nuremberg trials. The main target of the prosecution was Hermann Göring (at the left edge on the first row of benches). Credit: Work of the United States Government, Public Domain

Start with Tillerson

In the case of the climate crisis, it’s the industry itself that is driving crimes against humanity, and states that are complicit in issuing everything from drilling and infrastructure permits to generous subsidies – $20 billion per year in the United States alone. There are plenty of people in C-suites to hold responsible, with roles that more closely parallel those of Hermann Göring than Hermann Schmitz.

But to narrow the field of potential indictments, we might start with Rex Tillerson and other ExxonMobil executives – particularly good targets given that there’s been extensive documentation proving that the company’s top brass both knew about and then covered up the existence of climate change, even as they fortified their supply chains against climate impacts.

Of course, the legal hurdles to making such trials happen would be substantial. If the Nuremberg Trials were outside the box for international law at the time, trying fossil-fuel executives for crimes against humanity might well be in the stratosphere. For one, the US is not a party to the Rome Statute, so unless the UN Security Council were to grant a US court jurisdiction over the matter – which hardly seems likely – a case would have to happen in a country that is for anything to go before the ICC. And the legal doctrines that the ICC operates under were designed principally to go after states, not multinational corporations.

But if we were able to overcome those considerable constraints, what might trying fossil-fuel executives for crimes against humanity actually look like? Royal Dutch Shell, for instance, is based in the Netherlands – in the Hague, in fact – and is a party to the Rome Statute. In order for their executives to be tried for crimes against humanity, the ICC prosecutor would need to open an investigation to determine whether domestic courts in the Netherlands had not done enough to hold the offending parties accountable. The prosecutor could then use their proprio motu power to bring an indictment before the ICC, which would then hear the case.

Also Read: What Trump’s Decision to Pull the US Out of the Paris Climate Deal Means

Alternately, the Dutch government could refer the case to the court itself. Plenty of countries have crimes against humanity statutes, however, so a trial wouldn’t necessarily have to happen under the auspices of the ICC. And because companies like Exxon have operations all over the world, they could theoretically be tried in any country that has such statutes on the books, or that is a party to the Rome Statute. Options abound.

U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson takes part in a news conference with Canada’s Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland (not shown) on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, December 19, 2017. REUTERS/Blair Gable/File Photo

But none of these lengthy bureaucratic processes will kick off without massive public pressure, which in itself could bear fruit beyond indictments. Exciting as these trials might be, the most pressing work ahead is to decarbonise the global economy.

One obvious implication of calling people like Tillerson mass murderers is that their ilk should probably not be in charge of the world’s most powerful corporations; every piece of evidence we have suggests they’ll just keep killing. If we are going to embark on the managed and just transition off of fossil fuels that science is telling us we need, fossil-fuel executives simply can’t be trusted to oversee it.

So if in the long run we hope to bring fossil-fuel executives to court, the road there should make sure that their destructive companies are taken out of private hands and run in the public interest – that is, wound down as quickly as possible, with the first priority being to ensure a dignified quality of life for those workers who stand to be most affected.

While there are plenty of barriers to getting a conviction or even opening a case, the Nuremberg trials were themselves a kind of experimentation, wherein Allied forces effectively tested a new legal doctrine crafted to fit the specific atrocities committed by Axis forces, for which there wasn’t – to that point – an established legal framework for punishing. Confronting climate change – the greatest existential threat the world has ever known – demands thinking no less creative.