New Delhi: Only around 30% of faculty vacancies under the reserved category were filled at the Indian Institutes of Technology and Central Universities despite a year-long recruitment to fill these posts, the education ministry has told parliament.

Between September 5, 2021, and September 5, 2022, 1,439 vacancies were identified, against which only 449 faculty members were recruited, it said.

The dismal numbers come against the backdrop of the year-long ‘recruitment drive’, which began in September 2021, to hire faculty belonging to Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Other Backward Classes in elite universities, the Hindu reported.

The data was revealed after S. Venkatesan of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) asked this question in the Lok Sabha, when the minister of state for education, Annapurna Devi, was presenting data on this ‘recruitment drive’.

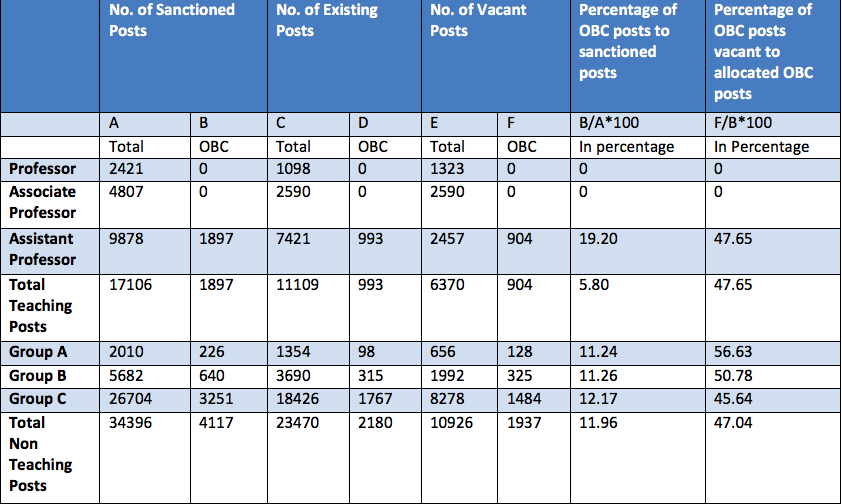

The Union government had directed 23 IITs and 45 Central Universities across the country to fill up vacancies in teaching positions under these reserved categories.

However, after more than a year, only 10 IITs were able to identify 342 vacancies in these categories for the positions of professors, associate professors and assistant professors. A total of 237 positions in these categories were filled at 19 IITs.

The newspaper quoted a data analysis done by the Ambedkar Periyar Phule Study Circle (APPSC) of IIT Bombay, which said that 13 IITs were unable to identify vacancies to be filled in this recruitment drive because they follow a “flexible cadre structure for faculty positions”.

The analysis further showed that 358 vacancies remained at 14 IITs at the end of this recruitment exercise.

The APPSC also found that no ST candidates were recruited at IIT Kharagpur, IIT Roorkee, IIT ISM Dhanbad, IIT Tirupati, IIT Goa and IIT Dharwad, during the one-year period. No SC candidate was recruited in IIT Roorkee.

It also found that most IITs did not recruit SC/ST/OBC candidates at the professor and associate professor levels.

What about Central Universities?

Government data showed that only 33 out of the 45 Central Universities had identified a total of 1,097 vacancies in reserved categories, of which only 212 were filled.

Among these 33 universities, 18 of them had recruited no SC/ST/OBC teaching faculty at all, the daily reported, citing the data.

The data also revealed that among these 18 Central Universities, the Jawaharlal Nehru University had identified 75 vacancies, the Banaras Hindu University identified 114 vacancies, and the Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University identified seven vacancies. None of the identified vacancies were filled in any of these universities.

At least 12 Central Universities did not recruit any faculty during this drive, saying that they had no backlog and could not identify any vacancies in these categories, the report added.

As of September this year, government data showed that Central Universities had a combined backlog of over 920 positions in the SC/ST/OBC categories for teaching faculty.

Violation of reservation policy

According to the Press Trust of India, the Supreme Court has recently directed the Union government to follow the reservation policy for the recruitment of faculty members at IITs as provided under the Central Educational Institutions (Reservation in Teachers’ Cadre) Act, 2019.

The Act provides quotas in teaching positions in central institutions for persons belonging to SC, ST, socially and educationally backward classes, and those from economically weaker sections.

The petition alleged that IITs are not following the guidelines of reservation as per the constitutional mandate.

It claimed the IITs were not following a transparent process of recruiting faculty members, which opened up a window for non-deserving candidates to enter the prestigious institutions through connections that increased the chances of corruption, favouritism and discrimination.

The plea also sought to cancel the recruitment of non-performing faculty due to a violation of reservation norms.

The Wire had in August reported, citing responses based on a Right to Information (RTI) query, that IITs are flouting reservation policy in faculty recruitment.

The authors of this report analysed the data, and said that “it appears as though the IITs are exclusively employing ‘upper-caste’ teachers.”