In my review of Mahmood Mamdani’s new book, Neither Settler nor Native – The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities, I questioned two dichotomies used to frame his analysis of the colonial process in the United States. These were, first, the distinction between colonialism and racism and, relatedly, the distinction between the expropriation of land and the exploitation of people’s labour. I wondered what is lost when we try to separate out these practices.

Neither Settler nor Native – The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities by Mahmood Mamdani.

In particular, I did not think that we could account for the transatlantic slave trade if such dichotomies were maintained. Thus, I asked: ‘Can anyone whose labour is made exploitable, not always already be expropriated from the land?’ ‘Enslaved Africans were expropriated from land too,’ I argued, adding, that, ‘they were forcibly taken from their societies and put to work as enslaved labour by the same colonial state.’

Professor Mamdani replied to my review with a question of his own, asking: ‘Were enslaved Africans also expropriated from the land ‘by the same colonial state’?’ His answer was that, ‘On the face of it, this seems a tall claim, untenable in light of the historical research so far’. Let me clarify my argument, for I think it was misconstrued by Mamdani. My point was that the same imperial-state – the British Empire – was responsible for both the colonisation of what became its Thirteen Colonies as well as for a large portion of the transatlantic slave trade. Indeed, it was the most dominant force in the ‘evil trade’ between 1640 and 1807, when it was formally abolished. Both the expropriation of the land of those who came be categorised as ‘Indians’ (the ‘natives’ of the Thirteen Colonies) and the exploitation of the labour of enslaved people categorised as ‘Negroes’ were critical to the success of the British colonial project.

This is not because, as Mamdani argues, that, ‘after an early phase that focused on expropriating the labour of Indians, the US took a conscious decision to displace Indian with African labour’ (my emphasis). This is a teleological argument, one which reimagines a long and unpredictable history as having been predetermined. We cannot read the enslavement of Black people and the exploitation of their labour as simply part of some long-hatched plan premised on the settler colonial ‘logic of elimination’ of the Indians, as historian Patrick Wolfe argues.

In contrast to such arguments, historian Andrés Reséndez has shown that the massive loss of life of Indians across the Americas was largely a result of the harsh conditions of forced labour they endured. With their immune systems fatally weakened, they were made susceptible to diseases that were new to them. To corroborate his argument, Reséndez points out that ‘one year before Europeans began reporting smallpox [in 1509, 17 years after Christopher Columbus’s landing], Española’s Indian population had dwindled to 5% or less of what it had been in 1492’ (my emphasis). The enormous loss of life was the outcome of numerous factors, none of which were part of a preplanned ‘logic’.

Once brought together under the force of ‘blood and fire’ (as Karl Marx put it), both those people racialised as Indians and as ‘Negroes’ were classified by the British imperial-state as aliens and not as subjects of the British Crown. People in both groupings were enslaved (the proportion of enslaved Black people was far greater, however). Both were formally freed from slavery in the late 19th century. Both were excluded from the group of rights-bearing persons in the Thirteen Colonies. Both groups were infantilised and legally considered as dependents. With the independence of the US in the late 18th century from the British Empire, neither Indians nor Black people (free or enslaved) were legally regarded as US citizens.

These facts make it impossible to support the claim made by Mamdani that in the United States there are two groups of people: native Indians governed by customary law and all others governed by civil law. From the tenuous establishment of the first British colony in 1607 until the constitutional amendments of the immediate post-civil war era of the late 19th century – the Slave Codes (the first of which was enacted by the British colony of South Carolina in 1691) ensured that Black people were legally set apart from those racialised as White.

Also read: When India Proposed a Casteist Solution to South Africa’s Racist Problem

Paying attention to US immigration laws further upsets the idea that all non-Indians were governed (albeit not equally) by civil law. Following quickly on the heels of the formal emancipation of enslaved Black people in 1865 and their incorporation into US citizenship in 1868, the US enacted its first immigration law in 1875. From its independence 100 years earlier to the 1875 Page Act, entry to the US followed the imperial model of mobility controls and placed no significant restrictions on people coming in.

The Page Act constructed two new categories of people whose entry to the US was specifically barred: ‘Chinese coolies’ and ‘prostitutes’ (aimed specifically at restricting the entry of women from China). State governed mobility into the US was, from that point on, racialised.

Yet, it was still not until the 1924 US Immigration Act that the entry of people from Europe was restricted and regulated (incidentally, also the same year that Indians were made US citizens). This new immigration law did not affect all Europeans equally. Like its predecessors, the 1924 law was racist: largely concerned with restricting the entry of Southern and Eastern Europeans, along with all Jewish people regardless of where they were moving from.

Significantly, people categorised as migrants are, like Indians, governed through the plenary power doctrine. Such powers insulate the US government from constitutional challenges by migrants, who, today, are the only group legally categorised as ‘aliens’. The result was that, like ‘Indian tribes’, migrants remain under the control of Congress. Indeed, migrants are governed by a different set of laws – US citizenship and immigration laws – than are any US citizens. I will return to this issue later.

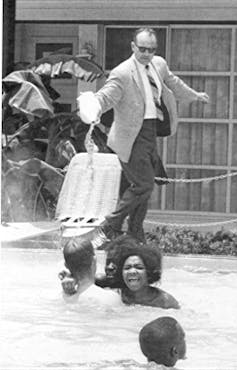

American Indian labourers, in 1906. Photo: US Reclamation Service, Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Of course, the fact that the binary of customary/civil law does not hold in the United States doesn’t fully address the issue of whether all these people can be considered to be colonised. Mamdani expressly disagrees with such a formulation. In response to my review, he asks, ‘what is the difference, historically and politically, between natives and immigrants, particularly forced immigrants (slaves, indentured servants)’? and ‘why draw a distinction between [these] two oppressed groups’? His answer is that we must draw a distinction between natives and migrants, because ‘colonisation is the conquest of land. Control over labour may or may not follow’. ‘Blacks’, he argues, ‘have been a source of labour and Indians a source of land, resulting in different governance regimes’. Black people are forced to endure White supremacy while Indians face colonialism. Thus, he argues, ‘racial oppression and colonisation are not the same thing, and neither are the solutions they call for’.

Is colonialism, however, only the conquest of land? Imperial states take control over as much land as they can in an effort to expand imperial territories and establish the sort of social relations necessary for the accumulation of wealth and power. After all, turning land into territory, as geographer Robert Sack usefully notes, is a ‘strategy for influence or controls’. Capture of territory allows imperial states to control people. In particular, colonial projects require people whose labour be exploited. Land and labour, together, are the necessary components for any colonial project.

Also read: Bringing Down Statues Doesn’t Erase History, It Makes Us See It More Clearly

Christopher Columbus knew this when he recognised that “the Indians of Española [on which he made land in 1492) were and are the greatest wealth of the island, because they are the ones who dig, and harvest, and collect the bread and other supplies, and gather the gold from the mines, and do all the work of men and beasts alike” (quoted in Reséndez 2016, 28).

Thus, rather than continuing to see people categorised as Indians, Blacks, and migrants as separate groupings, each with their own incommensurable experiences, I believe it is more historically accurate – and politically transformative – to understand that they came into being within a single field of imperial power. People in these groups continue to co-exist together in a single field of power I call the Postcolonial New World Order, a world of nation-states and ever-expanding capitalist social relations.

In this regard, we must also take into account Whiteness. In the initial period of colonising what is now the United States, the idea that workers from Europe were White would have been nonsensical. Indeed, as historians Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker discuss in their 2012 book, The Many Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic, all workers, including those from Europe, understood that ‘the “white people” were, in code or cant, the rich, the people with money, not simply the ones with a particular phenotype of skin color’. It was in the late 17th century when workers from Europe were decisively elevated above all others by colonial laws that invented the ‘White race’.

This broadening of the racialised definition of Whiteness was a critical aspect of containing solidarity amongst the subjugated. It was also crucial to the rulers’ strategy of ‘divide and conquer’, both within any particular colony as well as across the broader field of empire. The power of states – and of capital – grew in direct proportion to the consolidation of a White identity. Arguably, the success of strategies used to Whiten workers was an early moment in the imperial turn to biopower. Convincing (most) White workers that they were inherently superior to all others – and must be given preferential treatment, or else – was a key part of the process of making White settler colonies.

I am, of course, not saying anything that Mamdani has not already stated throughout his large and important body of work. Indeed, my own thinking of these matters owes a great debt to his. In his work on Uganda, Rwanda, Darfur and elsewhere, he brilliantly analyses just how much advantage imperial rulers gained by making distinctions between colonised people – and how these continue in today’s nation-states. Divided from one another through the law and its identitarian affects, people’s ability to resist ruling relations was – and remains – profoundly weakened. Again, as Mamdani has shown, the differentiation between native and migrant (and native and settler) have been particularly useful.

However, it is important to add that it is crucial that we not continue to see the world through an autochthonous lens (‘autochthons’ or ‘the indigenous’ being those who are regarded as the people of a place and, as such, the only ones with the legitimate right to govern). The world is not actually comprised of discrete, disconnected territories, each belonging to those people whom states define as its natives. People categorised as natives and non-natives are not wholly discrete people whose concerns are incommensurate. Rather, since at least 1492, all of us have been brought together through the shared space of empire(s). In this sense, colonialism is not only the conquest of land, it is not only the exploitation of labour, it is not only the denigration and oppression of the colonized: it is all these things all at once.

Also read: Kashmir Is the Test Bed for a New Model of Internal Colonialism

Imperial space was comprised of multiple colonies as well as multiple trading routes capturing and moving the workers necessary for the accumulation of wealth and power. In its early stages, it was forged by what historian Marcus Rediker calls the “four violences”: the expropriation of the commons both in Europe and in the Americas; African slavery and the middle passage; exploitation and the institution of wage labour; and the repression organised through prisons and the criminal justice system. Feminist philosopher Silvia Federici adds to our understanding of these shared experiences by showing that the persecution of women and the containment of their liberty were crucial elements in the globalising capitalist project of imperialism.

Thinking about colonialism as a set of practices carried out within an imperial space that encompassed many people across vast areas of the globe, is not about ‘seeking to expand and virtualise the notion of the native’, as Mamdani claims I wish to do. Neither is it to turn colonialism into ‘a metaphor which can incorporate all other forms of dispossession’. I understand colonialism to be about the expropriation of land, its transformation into sovereign/state territory, the exploitation of labour, and the denigration of the colonised. These are violent acts that most people in the world have experienced.

Colonialism expanded and accelerated after the formation of various European empires from the late 15th century onward, and particularly after the formation of the British Empire, which was the first to globalise capitalist ruling relations. However, as many scholars are showing us, these practices took place prior to the formation of European empires and, continue to be practiced in the so-called national liberation states.

Answering ‘the hard question of historical injustice’, as I believe both Mamdani and I wish to do, can be done – is better done, I would argue – by reorienting ourselves with a view afforded to us by the world that we’ve inherited, a world borne of – and still wrought by – violent strife and deep inequality but a single, shared world, nonetheless. The project of decolonisation – the project of freedom writ large – is and always has been, by necessity, a shared one.

Nandita Sharma is professor of sociology, University of Hawaii at Manoa and author of Home Rule: National Sovereignty and the Separation of Natives and Migrants (Duke University Press, 2020).