What did one of India’s greatest poets, who is also celebrated as one of the greatest poets of the pre-modern Persian canon, have to say about engineering, a profession of choice and aspiration for so many in modern India and elsewhere?

While many topics of interest to us today went unaddressed by pre-modern literary traditions, it turns out that engineering is as old a theme as Persian and Arabic literatures themselves.

Amir Khusrow (1253-1325), poet at the courts of successive Sultans of Delhi and the best-known devotee of the Sufi saint Nizāmuddin Awliyā, made it the central topic of one of his long poems – the Āiyna-yi Iskandarī or The Alexandrine Mirror, completed in 1302 in response to Nizāmī of Ganja’s Iskandarnāma or The Alexander Book of 1202.

Nizāmī, writing for a Turkic court in what is today Azerbaijan, wrote the life of Alexander of Macedon in two parts. The first related to his imperial adventuring and conquests and the second, his humbling by God into the role of one of the prophets anticipating the prophet Muhammad.

An elephant clock painted on Ismail al-Jazari’s manuscript on engineering marvels. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In Khusrow’s re-telling, Alexander was a “divinely inspired” Sufi king, not a prophet. This poetic licence made sense because Khusrow retold Alexander’s life for a distinctly different purpose than Nizāmī: to furnish his reader, above all Sultan Alāuddīn Khalji of Delhi who had given himself the title of ‘Second Alexander’, with a model of an ethical disposition towards engineering and engineers.

It is possible he did so because, as Khusrow’s friend and fellow courtier Ziyāuddin Barani complained, the Sultan had failed to adequately patronise the many Iranian and Central Asian artisans who had taken shelter in his capital after fleeing Mongol invaders in the West.

Whatever his immediate motivation, Khusrow modulated the praise of God with which his poems conventionally opened to present God as a world-engineer and the sole real agent in a creation whose every part (as in the Qur’anic vision of creation) locked like clockwork into the other. This implied that Khusrow’s Alexander, who was more inventor and patron of engineer-inventors than just a world-conqueror, was only a medium of God’s reason. He did not need to be humbled like Nizāmi’s Alexander.

Whereas Nizāmī’s opening verse was: “Yours, O Lord, is world emperorship”, Khusrow’s was an inversion of this in the same meter: “O Emperor of the world, lordship is yours”, thus already signalling that the poem to come would be less about God’s agency and more about His human medium, Alexander as philosopher-saint-king-engineer and patron of engineers.

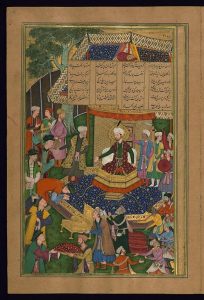

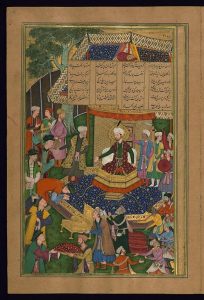

On this folio of a Khusrow manuscript, the Khaqan of China prostrates himself before Alexander. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What does all this mean for our opening question? What is Khusrow’s lesson on engineering? In a sense, his lesson is a Sufi amplification of what George Saliba, an eminent historian of science in Islamic lands, described as “an uninterrupted production of marvellous machines and toys from Hellenistic time and continuing well into Islamic times.”

In line with the earliest Arabic translations of Aristotle’s treatise Mechanica, Khusrow’s Alexander understands machines as devices by which things could be brought forth from potentiality to actuality. The Arabic word for such devices – hiyal, plural of hīla – literally means ‘tricks’, indicating as in Aristotle’s Greek, that the product was one that overcame natural resistance and executed functions contrary to natural tendency, ‘tricking’ nature.

But it also implied, as Aristotle said, that such devices had their origin in a maker outside themselves rather than within themselves like animate beings. They were simultaneously improvements on nature and dead.

Here we glimpse one of the oldest Islamic understandings of the work of literature as much as of technology: an ingenious mechanical and thus immortal imitation of an organic and thus mortal original. This is how Sa‘di’s Gulistān of 1258, the most famous work of medieval Persian prose (though mixed with verse), presents itself: a bejewelled verbal replica of a real rose-garden that would survive winters unlike the real one but only so long as it had human readers, eventually falling apart when human time ended with the Day of Judgement.

All artifice, for Aristotle’s Arabic-Persian interpreters, unfolded against such an eschatological horizon: prodigies of creaturely reason valuable only within the limited time humans were allotted. The ideal engineer was therefore civic-minded and god-fearing in the exercise of the intellect. Hence the memento mori of the concluding scene of Khusrow’s poem in which Alexander prepares for his own death by willing his corpse to be borne aloft that people may see that even he, world-conqueror, had died; and to be buried coffin-less in the dust of which all humans are made.

In this Mughal miniature attributed to Basawan of Lahore, Alexander is shown paying a visit to Plato. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Hence, too, Khusrow’s Plato who emerges from the sea to live in a cave, subsisting on seaweed, his emaciated body “purified by fasting”, showing its veins “like threads in amber” and refusing Alexander’s invitation to court but grudgingly dispensing valuable advice to the emperor. This was a Plato identical to the Socrates of Xenophon rather than the historical Plato himself; a Plato who tore himself away from the contemplation of nature to finally concede the importance of ethics and the ethical training of non-philosophers and thus towards the city, site of ethical cohabitation. It was the Plato of the earliest Islamic philosophers – al-Kindi (Baghdad, ca. d.866), Abu Bakr al-Rāzi (Rayy/Tehran, d.925) and al-Fārābi (Aleppo, d.950) – who saw Socrates as an exemplum of ethical transformation from severe asceticism to abstemious worldliness.

Not only did Khusrow belong to this Islamic reception of Aristotle, he may also have known, given his admiration for Sanskrit intellectual traditions, that the Sanskrit literature of western India around 1000 CE also absorbed something of the Abbasid Caliphate’s interest in marvellous machines. An example is the frame tale of Bhoja’s Śringāramañjarikathā or Stories for Śringāramañjari being told by a mechanical doll. But Khusrow subtly differentiated his lesson on engineering from that of his Islamic contemporaries and predecessors. The central mechanical

A manuscript, thought to belong to Nizami, shows Alexander building a wall against the people of Gog and Magog. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

device in The Alexandrian Mirror is a circular mirror Alexander has mounted on a watchtower in response to a complaint against Frankish pirates by seafaring merchants. The mirror discloses the location of the Frankish ships, allowing Alexander’s fleet to pursue them, clearing the waters for trade. The mirror episode itself appears right after a painting competition between the Greeks and the Chinese.

Khusrow re-tells a painting competition told earlier by Nizāmī and Rumi. In all three accounts, the winning side polishes the wall to mirror-brightness so that it only reflects what the other side has actually painted. In Khusrow’s version it is the Chinese who win, symbolising the superiority of Chinese engineering to Greek philosophy because the mirror, says Khusrow, was a Chinese invention to start with. In his pirate-disclosing mirror, Khusrow’s Alexander fuses together the functions of Jamshid’s world-disclosing goblet, the Chinese mirror and his teacher Aristotle’s astrolabe to produce a bricolage that valourised the artisanal multiculturalism of Sultanate Delhi.

In this, he echoed a foundational work of akhlāq or Aristotelian Islamic ethics, Nāsiruddīn Tūsī’s Akhlāq-i Nāsirī or The Nasirean Ethics of around 1235. Tūsī says the founder of a craft is superior to someone who knows it only slightly; and far superior to someone who lacks all capacity for invention and simply follows a master’s rules till he completes a task. He esteems invention most highly and then intelligent innovation on given inventions. This is the paradigm for Alexander’s bricolage in Khusrow.

But where Tūsī’s Nasirean Ethics teleologically submits its statements on craft to an overarching Aristotelian concern with individual and group perfection in the virtuous city where everyone tries to become more God-like, Khusrow’s poem is less interested in such civic progress. It instead concerns itself with the accomplishments of the engineer best exemplified in Alexander and Khusrow himself, but standing in principle for all humans.

Also read: What a Sufi Image of Cow Slaughter Tells Us About the Brahman in Classical Persian Literature

But it was precisely this profane valorisation of applications of the mind to machine-making that laid open Khusrow’s vision of technology to the risk of implying the sufficiency of the intellect. This was why he invoked a character already well known in earliest Islamic theology for asserting the sufficiency of the intellect – the Brahman.

Early in the poem, Khusrow tells a striking tale whose broad plot was completely derived from what were most probably oral versions of the written versions of the Advaitic treatise, Yoga-Vāsiṣṭha. It concerns a man near Damascus who doubted the literal possibility of Prophet Muhammad’s lightning-fast night journey to God’s throne and is humbled for it.

In this folio from a quintet by Amir Khusrow, a Muslim pilgrim learns a lesson in piety from a Brahman. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

On grounds of rational probability, the man suspects that the prophet’s ascension could only have been mental rather than actual. But when, one morning, he dips himself in the river he goes to bathe in he sees himself transformed into a woman in a distant land. The woman he has become gets married and, over 17 years, bears her husband seven children.

Then, one morning, the woman goes to the same river to bathe and, dipping herself in the water, sees herself re-transformed into the man she had been, his clothes left just where he had left them on that very dawn when he had immersed himself in the river. He instantly feels ashamed at having doubted the literal nature of the prophet’s ascension and grasps that God could suspend the laws of time and space.

And yet, it’s a strangely ambivalent tale because it is by insisting on the reality of the man’s rebirth – rebirth being doctrinally unacceptable in mainstream Sunni Muslim theology – that Khusrow insists, remarkably, on the reality of the prophet’s ascension. Whatever we make of this ambivalence, on the face of it The Alexandrine Mirror does humble the Syrian Brahman into submitting to Islam. Khusrow clarifies what this submission means in the context of this poem when he upholds this chastened Brahman as exemplary: it means restraining your intellect lest it harm your heart and faith.

But why choose an Indic tale to imply that the technological feats of Alexander’s life as Khusrow celebrated them, in fact, contained a warning against the excesses of the intellect?

Briefly, the answer lies in the earliest encounters, dating to around the ninth century CE, of Muslim and Jewish theologians with Brahman philosophers. “Early Islamic heresiographic traditions”, Sara Stroumsa argues, “attribute to the Barāhima the rejection of all prophets, on account of the supremacy and sufficiency of the human intellect”; and on account of the alleged impossibility that God might abrogate the laws of His creation and of the human nature He had created, laws He would have taught sufficiently to the first and last prophet, Adam.

Rendering the succession of prophets after Adam redundant or nonsensical, the Brahmans served as the straw men of Arabic rational theology against whom arguments continued to be made for the necessity and continuity of prophecy – Old Testament prophecy for Jews and Muhammad’s for Muslims.

But there was something else to this Brahman that was distinctive to Khusrow. Across his poetic corpus Khusrow sets up military and theological oppositions between the Hindu and Turk only to erotically dissolve them, this dissolution being one of the excitements of reading him as you realise that Khusrow has identified himself with his Brahman beloved as a Turkic Brahman or Brahman Turk. One of his 20 odd ghazals where the Brahman makes an appearance blends attributes of the Persian and Indian beloveds: the beloved as worthier than Somnath’s idol, as fire-worshipper and idolater too, his body as Jamshid’s world-disclosing goblet.

Also read: Rediscovering Forgotten Indo-Persian Works on Hindu-Muslim Encounters

The ghazal ends by identifying the beloved with Khusrow’s own writing, both the blackness of Khusrow’s Hindu or Indian slate and the chalk whiteness of his writing upon that blackness. It was arguably this kind of interchangeability of self and other that allowed the Brahman to so easily serve as an exemplum for Khusrow’s lesson in an ideally pious Muslim disposition towards technology.

Khusrow celebrated India in his poem Nine Skies for its distinctiveness in the Islamic world: not only was it distinguished by artisans from every corner of the Islamic world, it also boasted Brahman philosophers who put Aristotle to shame and the Sanskrit language he admired enough to try and learn. But he was also anxiously aware of the importance of technology in Sultan Alāuddin Khalji’s battles against Mongol incursions into the Punjab.

In the final analysis, his lesson on engineering assumed a disposition towards the ambient world that only diverted some of it towards human ends. It was a pre-capitalist artisanal ethic of engineering for civic benefit that worked on scales vastly smaller than scorched-earth capitalist approaches; and that was shot through with the Sufi awareness that the world, even when intellectually mastered with machines, brimmed with signs of what passed beyond the intellect and with reminders of human mortality.

Prashant Keshavmurthy is associate professor of Persian-Iranian Studies at the Institute of Islamic Studies, McGill University.