Bitasta Das was inspired by Indian folklore when she was asked to design a humanities course for IISc’s students that brought the natural and social sciences closer.

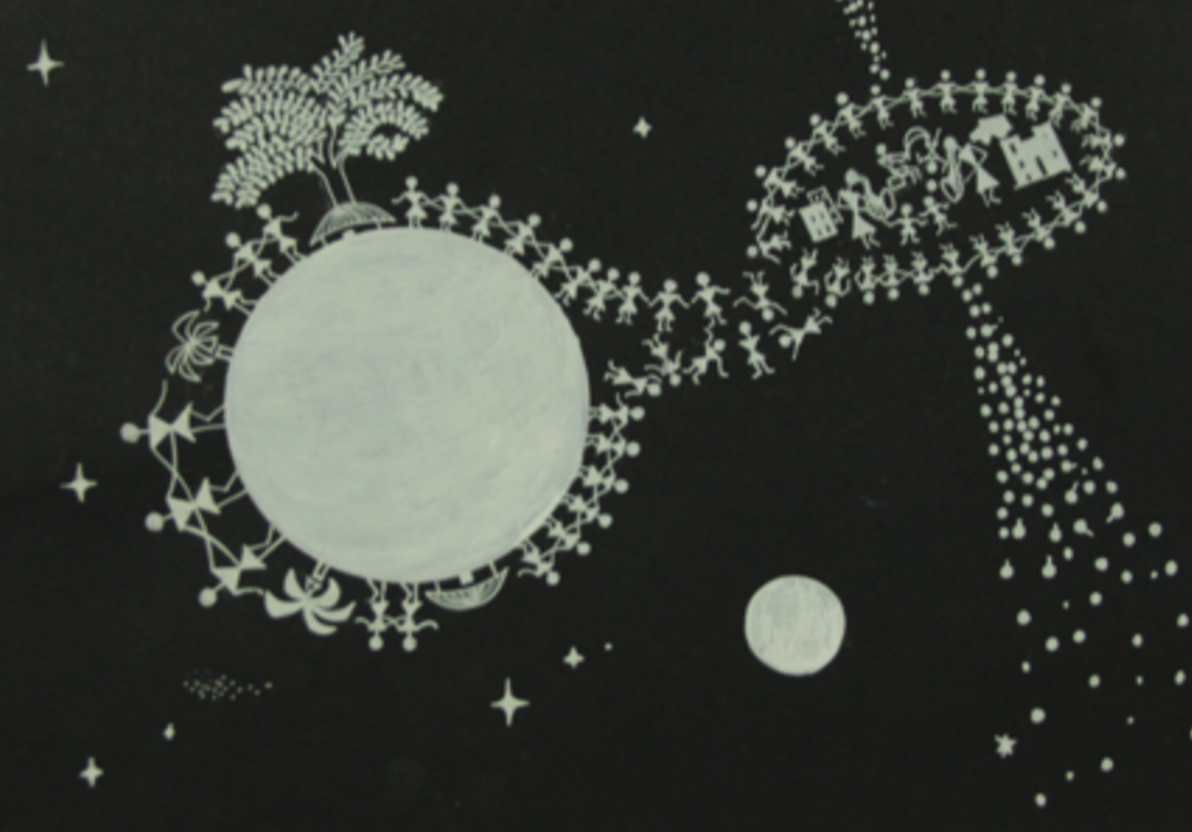

The concept of accretion depicted using an analogy of the rural population moving to cities in the Warli style. Credit: Lakshmi Supriya/IISc Press

Bengaluru: It is one thing to read that the dinosaurs became extinct because of meteors striking the earth. When you see it painted in the Sohrai style of tribal art, vivid colours on a muted red-orange, textured, imperfect background, it evokes something more than black and white text on a page can. Sohrai is usually done by the women of farming communities in Hazaribagh, Jharkhand, who decorate the mud walls of their homes with paintings of animals and plants during the autumn harvest festival. But they did not paint this scene; it was the work of science students at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), Bengaluru.

The students stayed true to the character of a typical Sohrai painting. “To emulate this, we created the base of the painting with plaster of Paris to create a texture of the mud walls and showed dinosaurs running away from blazing meteorites and volcanoes erupting in the background,” says Kartik Akhoon in an email, who was part of a group of students who painted this scene. This painting is one of several that were created by the undergraduate students of the class of 2016, as part of a course in their core curriculum. “The aim behind giving them this assignment was to see how they can express science beyond the convention,” says Bitasta Das, a research associate at the Centre for Contemporary Studies at IISc, who designed the course.

Extinction of dinosaurs by meteorites, painted in the Sohrai style of tribal art. Credit: Bitasta Das/IISc Press

Das, who has an undergraduate degree in botany and post-graduate degrees in cultural studies, was inspired by Indian folklore when she was asked to design a humanities course for IISc’s students that would bring the natural and social sciences closer. The stark divide between the arts and literature and the natural sciences occurred only in the 19th century. In the medieval ages, art and music were as much parts of education as were arithmetic and astronomy. Leonardo Da Vinci is perhaps one of the finest examples of a scientist and artist rolled into one. But, through the ages, with the sciences and arts moving away from each other, most scientists in the 20th and 21st centuries do not tend to think of art as a medium through which to disseminate scientific information.

The students echoed these sentiments when they had to make a painting using Indian folk art forms to depict scientific concepts. “Frankly, most of us were a bit skeptical about the assignment initially, and the reason for that is fairly straightforward. We were science students and knew very little about art,” says Kishalay De, another student of the course.

Such views are gradually changing. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, Massachusetts established a Center for Art, and Science and Technology in 2012 with the aim of integrating the arts with science and engineering research. MIT has for a long time now recognised the role that the arts play in science and technology education, and in cultivating a creative atmosphere, often leaving profound impressions on the students when they work in close contact with master artists.

Closer home, the Yashpal committee report on higher education in 2009 recognised the compartmentalisation of higher studies in India, and stressed that it is important that “the walls of discipline are porous enough to let other voices be heard.” At IISc, after more than a century of educating scientists, courses in the social sciences were included in the undergraduate core curriculum in 2012. And when designing a course for this first batch of undergraduates, Das decided that the students would find a course with a large practical component more interesting than something rooted in theory. Since science students are used to drawing diagrams, the use of paintings as a medium would be easier, and using folk arts would add another layer to their learning. “Folk genre of the country is so rich, and giving a science dimension would add up to the already rich treasure of folklore that we have,” says Das.

Nevertheless, the students were initially bewildered with the idea of using folk styles, but picked up on their unique characteristics soon enough. They were split into groups and had the freedom to choose the topic and the style of painting. De’s previous study on accretion disks led to his group’s painting. Accretion disks are formed by matter rotating around a massive central body, resulting in a spiralling-in of the orbiting matter into the centre because of gravity. The group used the Warli style of painting practiced by tribes in Maharashtra and along the border with Gujarat. A simple form of painting on the mud walls of houses during celebrations, it uses only circles, squares, triangles and whites. Depicting the massive central object as large cities, the villages around them as the orbiting matter, and the movement of people from the villages to the cities, the group portrayed the concept of accretion disks. “We thought it was a fairly good piece of work, particularly because we brought out an astonishingly clear similarity between a well known physical concept in astrophysics to a trend in the society,” says De.

Another group chose the style of painting that originated near the Kalighat temple in Kolkata in West Bengal in the early 19th century. Made in the style used by Jamini Roy, heavily influenced by the Kalighat form, the painting depicts the invention of zero by the Indians and centuries later its popularisation by the Arabians. The two disparate places are connected by a wormhole. Other paintings show varied concepts such as human evolution and the metamorphosis of a caterpillar into a butterfly (painted on glass in the church art style).

The invention of zero by Indians and its popularisation by the Arabians, the two different times and places connected by a wormhole. Painted in the style of Jamini Roy. Credit: Lakshmi Supriya/IISc Press

In another corner of the IISc campus, more than a year after these paintings were done, a blank wall outside a laboratory and the artistic talents of one lab member converged. Tejeswini Padma was working in Sandhya Visweswariah’s lab at IISc as a researcher and happened to present Visweswariah with a painting. Struck by Padma’s artistic capability, she asked her to paint something for the blank wall outside the lab.

Padma has an undergraduate degree in biotechnology and an interest in art. She says that if she had had the courage, she might have pursued a course in the arts rather than in engineering. Visweswariah gave her complete freedom to paint, with the only proviso that the she represent the science being done in the lab. “Just for the sake of this art, I read up so much. But if it was just ‘read this much,’ I wouldn’t have. It wouldn’t have motivated me that much,” says Padma.

Depicting the scientific work in the form of paintings required a deep understanding of the complex science and a liberal dose of imagination. One of the themes the lab is studying, using the mouse as a model, are the reactions produced when a particular receptor in the stomach binds to a ligand, which maintains the salt balance in the stomach to prevent diarrhoea. Pathogens such as Escherichia coli produce a toxin that is similar to the ligand but has a more intense reaction, causing a bloated stomach and traveller’s diarrhoea. Her first painting has a mouse with a bloated stomach that occupies the centre, ligands, finger-like receptors and the toxins produced, all rendered artistically. A Viking boat represents a connection with Norway, where a genetic mutation has been discovered in a family of 32 who have congenital diarrhoea. A patch of cell-like structures represents the cells cultured in the lab and how they look under the microscope.

Another painting with a bright red background represents studies on bacterial enzymes that affect the lungs. The painting shows a chest X-ray, the bacterial colonies grown on culture plates and a representation of a single bacterium. A bicycle stands in for an enzyme called adenyl cyclase that produces ATP, with the spokes representing the 16 types that are produced. The ATP is broken down in slow growing bacteria, represented by the tortoise holding a wrench, which can modify the cell wall.

A trailer of one of the themes being studied in Sandhya Visweswariah’s lab at IISc. Credit: Tejeswini Padma

Compared to the artwork produced by the students, these paintings are much more complex and represent several ideas in one frame. Made on canvas with acrylic paint, they are also large. “What I have done here is like a trailer to a film,” says Padma. On the paintings made by the students, she says that such ideas can make it easier for understanding one particular concept. Curiously, neither Das nor Padma were aware of each other’s efforts until recently.

IISc is now actively promoting the art in science – in what may be the first of its kind in India. Padma is now working on scientific paintings full time and has several works commissioned by IISc. Das has compiled the paintings created by students and the IISc press published them as an ebook called Arting Science in June 2016. The institute is showcasing all these paintings on its website, with plans for using such artwork in various in-house publications. The students, although unsure in the beginning, came to enjoy the work in the end. Some expressed that the course broadened their worldview and abated their indifference toward the arts, forcing them to think about their science from a completely different perspective. “Contemporary science and engineering students have a very narrow scope of vision and it wouldn’t hurt us to have an additional artistic knowledge,” says Akhoon. For Tanmoy Pal, another student, it took him on a personal journey that enabled him to discover the artist in himself.

Visweswariah has similar feelings. “The best scientists usually are great musicians or painters or great readers. Truly great achievements in any discipline require a person to be aware and excited about other spheres of human activity,” she says. With the efforts put in by IISc in showcasing these artworks, Visweswariah believes that it will get more people to think about such things. And scientists will perhaps think of spanning the science-arts divide more colourfully.

Lakshmi Supriya is a scientist and a freelance writer. She lives in Bengaluru.