Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke to Times Now, his first TV interview since taking office, on 27 June 2016. As with his Wall Street Journal interview the month before (critiqued here), Modi covered a lot of ground, from economic reform to domestic politics to foreign policy. Here we specifically examine some of his claims regarding his ambitious development agenda.

Modi has developed a flair for presenting evolutionary policy steps built on his predecessors’ work as revolutionary and original contributions to national development. Take his repeated claim regarding the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY):

It’s not in words but in actual achievement. I had said that within a given time frame, we will open bank accounts for the poor. For something that had not been done for 60 years, setting a time frame for it was in itself a risk.

The Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojna is not only about opening bank accounts for the poor. Because of this the poor are feeling that they are becoming a part of the country’s economic system. The bank that he was seeing from afar, now he is able to enter that bank. This brings about a psychological transformation.

Very moving, but it’s a bit much for Modi to hog the credit. It is true that the PMJDY has accelerated the spread of basic savings bank deposit accounts (BSBDA), and increased their usefulness by adding life and accident insurance. But the entire architecture of financial inclusion (BSBDAs, Aadhaar, electronic payments, RuPay cards) was created and implemented long before Modi took office.

In the two years before Modi, the UPA opened 44 and 61 million BSBDAs respectively, which under Modi jumped to 147 million in 2014-15 and 67 million in 2015-16 (see table below). Assuming conservatively that another government would have opened 61 million BSBDAs per year (as the UPA did in 2013-14), the Modi effect looks something like this:

A solid step forward? But with 243 million bank accounts already in place before he was sworn in, the only thing we are seeing for the first time is such self-congratulation.

We have taken up construction of toilets. I had gone to Chhattisgarh and had the opportunity to get the blessings of one mother. An adivasi mother heard about the scheme for building toilets. She sold her four goats and built a toilet. That 90 old mother uses a walking stick and goes around the cluster of 30 or 40 houses in the tribal village and has been spreading the message to build toilets. This change is becoming the reason for the change in the quality of life.

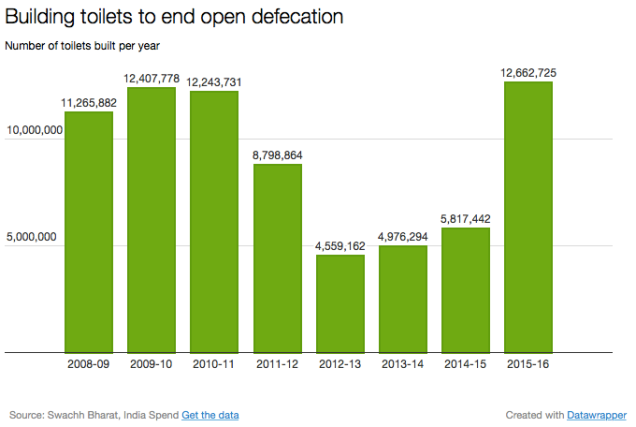

Encouraging yes, but hardly novel. There is little doubt that open defecation is a public health hazard that contributes to the spread of diarrhoea, intestinal worm infections and other diseases that cause stunting, malnutrition and even death among young children. Which is why the government has for decades sought to furiously build toilets throughout rural India — with a discernible bump in Modi’s second year:

To be fair, Modi isn’t claiming exclusive credit here, and he is right to highlight the importance of behavioural change in his adivasi mother example. Open defecation in rural India has dropped much more slowly than in, say rural Bangladesh, partly because Bangladesh has targeted social norms in addition to building toilets. The UPA’s Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan (launched in 2012-13) and the current Swachh Bharat Abhiyan both recognised this reality, and Modi’s vocal advocacy could play an important role here.

That said, reports still suggest that behaviour change is lagging behind (here, here and here). The important point is that toilet construction is necessary but insufficient by itself to reduce open defecation.

You must have seen that the maximum electricity generation since Independence has occurred this year. The maximum amount of coal mined has been in this year. The maximum length of roads being constructed daily is happening in this year. The fastest loading and unloading of steamers at sea ports is happening now.

As previously explained in Modi’s autopilot achievements, there is always a good chance in a rapidly growing economy that every year will see one or the other record broken. Maximum electricity generation since independence? True for every year since 1975-76. Maximum coal mined? True for every year since 1980-81 (except 1998-99). Maximum length of roads being constructed? Probably true (but look here for context). Fastest loading and unloading of ships? True for every year since 2012-13. These claims work well on Twitter and Facebook, but are mostly meaningless in the Indian context.

After independence, for the first time, we have brought in Pradhan Mantri Fasal Beema Yojana which can cover maximum number of farmers. The farmer will have to pay only 2%, the government will take care of the rest.

Yes, Mr Prime Minister, if we pretend that the following two never happened: the NDA’s 1999 National Agricultural Insurance Scheme (NAIS) and the UPA’s 2013 National Crop Insurance Scheme (NCIS — which clubbed the 2010 modified NAIS, the 2007 Weather Based Crop Insurance Scheme and the 2009 Coconut Palm Insurance Scheme). And the NCIS’ Hindi name has a familiar ring to it: the Rashtriya Fasal Bima Karyakram. The one time the UPA manages to instituted a programme without a Gandhi name attached to it, Modi replaces “national” with “prime minister”.

The new insurance scheme is certainly an evolution over its predecessors: premium rates are lower (with the government subsidy and contingent liabilities correspondingly higher), and harvested crops are now covered nationally (earlier this only applied to coastal regions). First time after independence? I don’t think so.

We have brought in Soil Health Card. We have a Soil Health Abhiyan. The farmer will know the fertility of the land through it. Whether a fertilizer needs to be used or not, the farmer will understand. On an average, a farmer with 1 hectare of land will be able to save Rs 15000-20000. So we have brought in scientific methods.

Another unfortunate exaggeration. Soil health cards have been in use since 2003, and even the UPA issued around 2.8 crore cards in its final three years, bringing the total in circulation to around 6.8 crore (source here). Modi relaunched the scheme on 19 February 2015, promising to issue 14 crore cards over the next three years, but progress has been slower than expected. The number of cards issued as on 28 June 2016 is 2.1 crore, short of the required pace albeit faster than what the UPA achieved.

But before you break out your gau-champagne, one reason is that farms were earlier being individually tested. Soil samples are now being taken from 10-hectare (in rain-fed areas) or 2.5-hectare (in irrigated areas) zones, which in effect clubs several farms together. This has speeded up the process of issuing soil health cards, but has made the results potentially less relevant to individual farmers.

Now like the initiative we have taken, we have started the Mudra Yojna. More than three crore people in the country comprise washermen, barbers, milkman, newspaper vendors, cart vendors. We have given them nearly 1.25 lakh crore rupees without any guarantee.

The Micro Units Development and Refinance Agency (MUDRA) Bank certainly sounds like a good idea. But there are literally dozens of financing schemes for micro-, small- and medium-sized entrepreneurs. The MUDRA Bank, currently a unit of the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI), appears to be a supercharged version of SIDBI’s Credit Guarantee Scheme that over about a decade until 2014 had given Rs 76,650 crore in guarantees to 1.6 million small entrepreneurs (as this Business Standard article points out). And the wisdom of dishing credit out via “mega credit campaigns“, which used to be called “loan melas” in an earlier era, will only be known over time.

The bottomline: Modi is overseeing a range of policy initiatives, many of which could well bear fruit. But as his good friend Barack once said: “You didn’t build that.”

Amitabh Dubey analyses politics and government policy. He also blogs at chunauti.org, where this article originally appeared. Read the original article.