The three-judge Supreme Court bench headed by Chief Justice of India Dipak Misra and comprising Justices Ashok Bhushan and Abdul Nazeer has heard the Babri Masjid case ten times, but is still struggling to decide if the matter should be referred to a constitution bench of five or more judges.

Article 145(3) of the constitution mandates the composition of five-judge benches for deciding any case involving a substantial question of law relating to constitutional interpretation. While the constitution benches have heard several cases in the recent past, ranging from instant triple talaq to passive euthanasia to the latest Delhi statehood case, besides finalising such benches for a number of religious matters including the Sabarimala temple entry ban case and Parsi ex-communication case, the hesitation in referring the sensitive and challenging Babri case to a larger bench is surprising. If the three-judge bench hears it, then Babri will be heard as an ordinary title dispute and constitutional questions will not be looked into.

The perils of ‘privatising’ a public dispute

To hear Babri as a title dispute is a judicial stratagem to reduce the ‘scope of the conflict’. An understandable, easy strategy, but not necessarily the correct one. Gary Jeffrey Jacobsohn, in a different context, argued that framing the “scope of conflict” in politics is determinant of the realm of justice. ‘What is justice’ depends upon what is framed as a justiciable question, and a narrow framing might qualify as justice in form but not substance. In other words, what answers you get depends on what questions you ask. Supplying the terms of reference is, therefore, one of the most consequential steps towards the satisfactory adjudication of a dispute.

Does framing Babri merely as a title dispute, resolvable by historical facts and legal titles, allow the court to ask all the relevant questions that are crucial for bringing closure to the ‘wounded psyche’ of the nation? Could such a framing capture adequately the anxieties and disagreements of the parties from the impugned judgment of the Allahabad high court and allow them the argumentative space to scrutinise its inner logic and assumptions? The constitutional court of last resort, the ‘Supreme’ Court of India after all, should have access to all administrative and constitutional powers, besides enabling managerial apparatus and paraphernalia to engage with any question and reconsider any judgment that helps conclude a long dispute comprehensively and equitably. We do not crave a Supreme Court that cannot assert its will and capability in wading through the thicket of precedents and clear the cobwebs of jurisprudence in a case that has been framed as the ‘second Partition’.

To be clear, the Allahabad high court judgment was not a finding on facts, as much as it was a comparative valuation of faith and the subsequent translation of faith into jurisprudence. However, to take faith at face value is one thing; to employ that faith in a legal framework to shape rights is quite another. It larks at the liberal-constitutional common sense that says what rights we have has little to do with our identitarian beliefs.

The Allahabad high court verdict walked all over this constitutional consensus by privileging Hindu belief about the birthplace of Ram and recognising the title of Shree Ram Lalla to the space under the once-existing dome of the Babri Masjid. In so doing, it relied on the catastrophically circular logic of adverse possession and dispensability of a mosque to the practice of Islam. Perverse, since the argument about dispossession and disuse of a mosque since 1949 was made possible in the first place by interlocutory restraining orders and the respect shown for these orders and ‘rule of law’ by Muslims. The fact is that the disputed structure was very much being used as a mosque when idols were smuggled in in 1949.

Even more tragic was the judicial insight that somehow the right to pray in mosques was not an essential feature of Islam and hence, did not enjoy constitutional protection. This was despite the widespread Muslim belief that mosques were integral to Islam, just as any religious place of worship was essential to the practice and profession of that religion. What mattered, though, was not what the community believed but the judges’ interpretation of its beliefs. The judges reasoned that Muslims could pray anywhere and were not scripturally bound to pray in a mosque only. One wonders if this wool-headedness will claim its victims in the upcoming Sabarimala temple entry case and court will play the gatekeeper of faith yet again.

However, it is particularly revealing that this skepticism turned to shraddha in 2010 when judges refused to ponder on the ‘impossible’ task of examining the Hindu belief about the birthplace of Bhagwan Ram. This was the right stance, made suspicious only by its selective application by the court. The metaphorical mandir of the Ramjanmabhoomi Andolan was erected on these two pillars of phoney thought gifted to us by the precedents in Masjid Shahid Ganj case (1940) and M. Ismail Faruqui (1994). Any sincere attempt to examine the rationale of the high court order needs to be empowered enough to take a hard look at wisdom of M. Ismail Faruqui and the relevance of Shahid Ganj to the special genealogy of the Babri dispute. But the court seems keen on entering the wrestling ring with its hands tied behind its back.

The Supreme Court of India. Credit: The Wire

Judicial temptation to privatise Babri to a title dispute might be a well-intentioned modus vivendi to contain passions and ramifications of the verdict. But it is destined to fail miserably in a case that has had a very public and politicised life so far. The court seems to misunderstand the nature of claims in the Babri dispute as one shaped and exhausted entirely by the minutiae of law and think that a technical, legal adjudication will illumine the trenches of social and political contestations around it. The distressing fact is that legal claims have been relentlessly reshaped by the changing facts on the ground to mirror the ascendant claims of the Hindu Right. This attempt to reduce it to a mere narrow title dispute will only privatise the psychological scars and grief of the Muslim community, while turning a blind eye to deliberate shifting of facts on the site. It will invisibilise what needs to be brought out in the open and hide away the systematic and insidious shifting of the secular ground in India.

A counter-majoritarian court is the last institutional resort for minorities in a polity which has turned dangerously domineering and communal. The constitutional duty of the court to safeguard ‘substantive secularism’ would entail the court accounting for ‘systemic discrimination’, which in turn has to start with broad framing and understanding the “socialisation of dispute”. The history of the Babri dispute hides a pre-history of administrative, political and judicial complicity at each turn.

The invisible “pre-history” of the dispute

Even when we remember that the Babri mosque was built upon the birthplace of Lord Ram, the fact that a mosque functional for four centuries was razed by hammers and spears cannot be deliberately disremembered. Since ‘judicialisation’, the dispute has travelled inexorably in direction of favouring the Hindu Right. State instrumentalities – the district magistrate, lower courts and state and Central governments – have all played their part through connivance, condonation or a ‘by-stander’ approach.

Sample this:

First, the district magistrate connived in smuggling Ram idols into the inner complex on the night of December 22, 1949, which was called as ‘chamatkar (miracle)’. The overnight smuggling led to a flow of Hindus inside a functional mosque standing for 400 years.

Second, in 1949, the Muslims stopped offering namaz in deference to authorities’ plea but the Hindu side escalated prayers gradually.

Third, the Rajiv Gandhi government opened the gates of the Babri Masjid to all Hindu pilgrims in 1986, while Muslims refrained from offering namaz showing deference to ‘due process”.

Fourth, despite written assurances from the Central and Uttar Pradesh governments to the Supreme Court, the Babri mosque was demolished on December 6, 1992. And while the mosque was reduced to dust, the Ram sevaks left behind a “makeshift temple” on the site.

Fifth, the Central government acquired the Babri complex by passing an ordinance which later became the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act. Section 7 of the Act preserved ‘status quo’ as on January 6, 1993 instead of December 6, 1992. The implication being that while prayers could continue inside the makeshift temple, the Muslims were debarred from even entering the land where the Babri mosque stood for 400 years. In effect, the state validated the act of ‘vandalism’ by not touching the makeshift temple.

Sixth, the Supreme Court inflicted further humiliation on the Muslim psyche by not only validating the ‘Acquisition Act’ but reasoning that any mosque can lose its religious significance owing to it disuse and as namaz can be offered anywhere, so a mosque is not as essential feature of Islam.

The illegality of demolition was further accentuated by excavation carried out on the site of demolition by Archaeological Survey of India, whose report was relied upon the Allahabad high court to confirm remains of the temple before 1526. Noted legal scholar late T.R. Andhyarujina observed, “It is an elementary rule of justice in courts that when a party to a litigation takes the law into its own hands and alters the existing state of affairs to its advantage (as the demolition in 1992 did in favour of the Hindu plaintiffs)….the court would not allow an act of lawlessness to benefit the party that indulged in it. This elementary rule of justice, the Allahabad HC judgment ignore(d)”. As a nation, we forgot the illegality of demolition and started exploring the possibility of building a grand Ram temple. How have we become so numb? The excavation on the site and subsequent reliance by Allahabad high court was akin to mutilating the corpse of Babri.

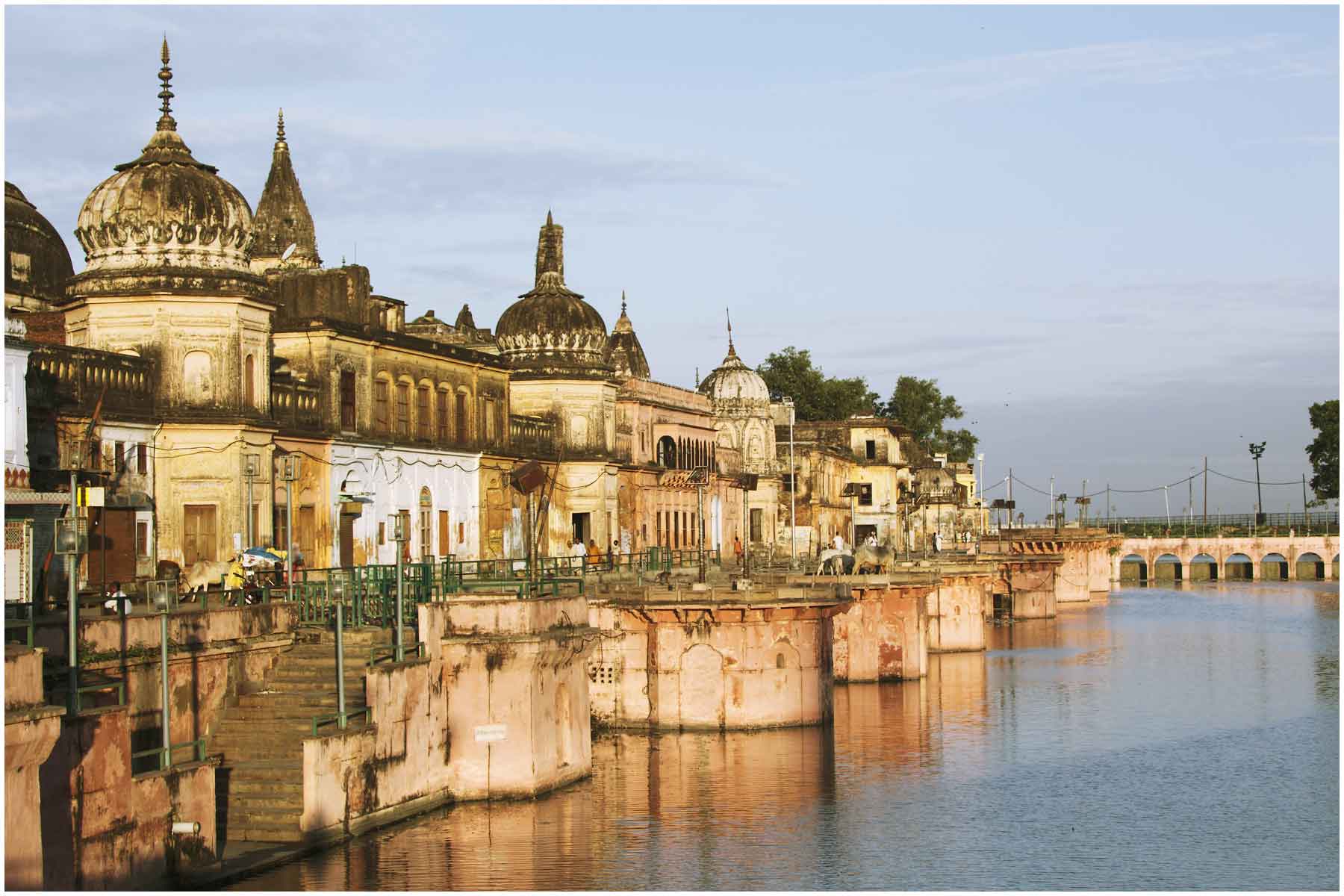

Ram Paidi ghat, Ayodhya. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In addition to the title of the land, constitutional confusions on the mosque forming an essential practice of Islam or a mosque losing its religious significance due to adverse possession needs to be authoritatively addressed. This is the last chance for the top court to exorcise the ghosts of Ismail Faruqui before it contaminates the body politic irreversibly. In Faruqui, the court placed reliance on a 1940 privy council case, Masjid Shahid Ganj vs Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee, Amritsar where “it was held that where a mosque has been adversely possessed by non-Muslims, it lost its sacred character as mosque. Hence, the view that once a consecrated mosque, it remains always a place of worship as a mosque was not the Mahomedan Law of India as approved by Indian Courts.” A final blow was dealt by Faruqui in para 80 by holding that “…a mosque is not an essential part of the practice of the religion of Islam and Namaz. (prayer) by Muslims can be offered anywhere, even in open. Accordingly, its acquisition is not prohibited by the provisions in the Constitution of India.”

Senior advocate Rajeev Dhavan has consistently argued before the current bench that this comparison on status of a mosque is a “cross on chest” and needs to be re-looked. Senior counsel K. Parasaran representing the Ram Lalla on May 17 argued that Ayodhya is of “particular significance” to Hindus as a place of pilgrimage, just as Mecca and Medina are for Muslim pilgrims. A deft argument to hint at greater comparative significance of Ayodhya vis-à-vis Babri. The court should be wary of taking the bait here and playing the referee between religious beliefs. Either the beliefs have to be taken at face value or they have to assessed against a shared standard like constitutionalism. The kind of amateur theology masquerading as judicial reason that assesses different faiths against each other will take us down the road to ruin.

Instead, the court should frame the issue as one of the extent to which religious faith matters in shaping legal claims. It would be too naïve to not remember the permanent poisoning of public discourse by the casual observations of former Chief Justice J.S. Verma in 1996 about Hinduism as a “way of life”. There too, the framing of the dispute was of the essence. Instead of asking if Hinduism was a religion or a way of life, the court could have asked why should it matter to secularism if a religion is also, and unsurprisingly, a ‘way of life’? Should religious appeals in electoral speeches be condoned only because they are ways of living? Public discourse on the Babri dispute is already being shaped by observations about disuse, dispensability and adverse possession made in the five-judge bench of M. Ismail Faruqui. Evading the scrutiny of Faruqui’s logic citing rules of res judicata would be tantamount to judicial abdication. It would also amount to mocking the cumulative grievance of one community and shying away from its responsibility as a ‘court of last resort’ to make politics accountable to constitutional values.

A test case for “counter-majoritarian” and “rule of law” court

The successful adjudication of the title dispute in Babri and the cooling down of communal passions will depend largely on the torch of reason brought to bear by the court in this case. The Supreme Court is the natural site of negotiation for a case that has evaded social and political settlement so far only because the court still evinces credibility and respect. Its recent ruling in the Delhi statehood case will only shore up its credentials as an institution committed to authoritative and fair resolution of disputes on the benchmark of constitutional morality.

Whichever way one sees it, the Babri case is a test case of constitutionalism and rule of law. Beyond the philosophical paradigms and phraseology, what do they concretely mean for the citizens? Does state complicity, the slow wheel of judicial process, judicial condonation and systematic humiliation of one community at the hands of the majority count as violations of the ‘rule of law’? If law has condoned the transgressions of a majoritarian mob, legitimised the criminality of demolition by excavating the ground beneath, swung unevenly on the question of faith and punished the minority community for keeping faith in due process, what does it portend for the rule of law? It means that sovereignty of law is impinged by numbers on the ground. The Supreme Court has to remind itself that the rule of law requires no one to benefit from their own wrongs. The competing claims to the disputed site cannot be heard while forgetting that there once was a mosque. The presence of Babri’s absence, to borrow Mahmoud Darwish’s evocative phrase, must chastise the court at all times from creating a new ‘normal’.

While the court cannot distil the sticky quagmire of ancient beliefs, it can go some distance in making those beliefs irrelevant to the question of citizenship. The verdict should have a ‘notwithstanding’ quality to it so that it is not assailed on ancient biases and basic instincts. It cannot do the work of politics, but it can take account of how social and political claims affect the law and get affected by it to reason its way out of the labyrinth. The astuteness and sensitivity of the court’s approach in dealing with these claims will determine the respect for the verdict. Just as Babri presents an opportunity to assert the sovereignty of law, it also lends a context to meditate on the self-imposed limits of the law.

The Places of Public Worship Act 1991 draws August 15, 1947 as the date from which status quo of all religious places of worship would be preserved. What does this mean for the constitution’s relationship with the pre-constitutional, even medieval past? It means that our politics resolved to build itself as a unique community of principle from 1947 and eschew a certain endlessness in its proceedings. It breaks from the past to escape its tyrannous hold over our imaginations of the self and society in the future. All of these hopes and anxieties will register themselves in the imprint of the Babri verdict. If there is a case which screams content-filling to the rhetoric of rule of law, it is this case. However, it would require a sensitive and sure-footed court to make it a ‘rule of law’ question and not dress over the million cuts on the Muslim psyche by framing it as a mere title dispute. The court has to ensure that the tremors of Babri do not subdue the sinews, nor submerge the sub-structures of constitutional faith.

Satya Prasoon is a lawyer working with Centre for Law and Policy Research where he is associated with Supreme Court Observer Project. He tweets at @SatyaPrasoon. Views are personal.