A recent decision of the Supreme Court of India laid down guidelines for the chief justices of high courts to invoke Article 224A of the constitution to appoint retired high court judges on an ad-hoc basis. While many may breathe a sigh of relief in the backdrop of a high number of vacancies, delayed appointments and mounting arrears owing to limited functioning during the pandemic, it is critical to first understand the change that is likely to result from this judgment in practice.

There are two steps to be fulfilled for high courts to make use of this provision.

Step one, the high court concerned should have made recommendations for more than 20% of its vacancies, without which Article 224A cannot be invoked. The judgment states that the reason for this requirement is to ensure that Article 224A is not resorted to as an easy alternative to judicial appointments made through the regular process.

Also read: Why Is it So Hard to Fill up the Judicial Vacancies in Our Courts?

Step two, the judgment states that there can be multiple trigger points for appointing ad-hoc retired judges and lists the below five events as triggers (it is important to note here however that the judgment does not state that this an exhaustive list):

1) If a high court has vacancies that are more than 20% of its sanctioned strength

2) If cases of a specific category are pending for more than five years

3) If over 10% of the high court’s cases are pending for more than five years

4) If the rate of disposal of cases is lower than the rate of institution of cases (‘case clearance rate’)

5) Even if the number of old cases is low, it is likely there will be a situation of mounting arrears due to a consistently low case clearance rate for a year or more

Therefore high courts that pass step one and fit within one of the five criteria mentioned above can begin the process for appointing retired judges to act as high court judges on an ad-hoc basis. The number of vacancies that each high court must have made recommendations for in order to pass step one can be seen in Figure 1.

Source: Authors workings derived from (i) sanctioned strength as available in the Supreme Court’s latest annual report, i.e. of 2018-19, and (ii) current judge strength as shown on the website of each high court as on April 22, 2021.

While there are four high courts (Manipur, Meghalaya, Sikkim, and Tripura) that currently have no vacancies, the high court of Allahabad, which has the highest sanctioned and working strength, also has the highest number of vacancies. It needs to have recommended the most number of names before it can invoke Article 224A.

Some high courts need to have recommended as low as one name for appointment in order to invoke Article 224A. Assuming the remaining 21 high courts (all except the four with no vacancies) have made the required number of recommendations to invoke Article 224A, how many of them satisfy any of the five events in step two?

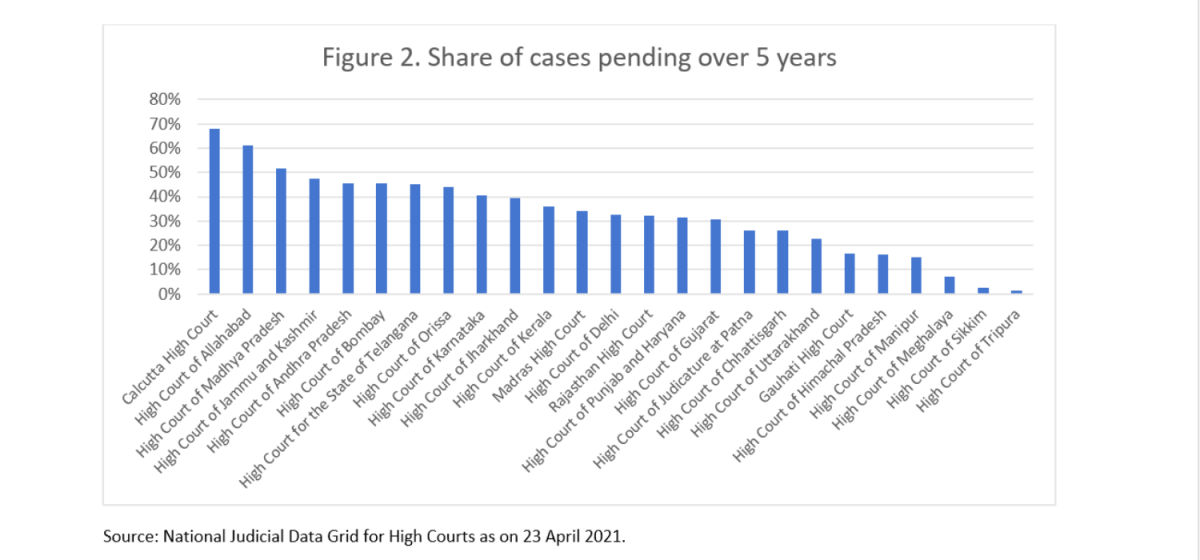

Let us look at the third event (where data is easily accessible) – high courts that have more than 10% of their pending cases being over five years old – as per the National Judicial Data Grid, all of the remaining 21 high courts have over 10% of their cases pending for more than five years.

We therefore now know every high court with vacancies can invoke Article 224A if they have made recommendations for the required number of vacancies in step one.

But before we think this will make a substantive difference to the current functioning of these courts, it must be borne in mind that the judgment of the Supreme Court also specifies that the number of ad-hoc judges in each high court should be between two and five.

To put this number in perspective, let us compare two courts with a similar number of pending cases but varied working judge strength, the high court of Bombay and the high court of Rajasthan. As of April 23, 2021, the high court of Bombay had 5,51,494 pending cases and 62 judges, while the high court of Rajasthan had 5,41,613 pending cases and 23 judges.

Also read: What Is Stopping Our Justice System From Tackling the Cases Pending Before Courts?

Even if the recent judgment enables the high court of Rajasthan to appoint five judges on an ad-hoc basis, I would be cautious in hoping for a definitive improvement when the high court of Bombay would have over double its strength and still a similar number of pending cases.

Sure, a few more cases would be heard and possibly disposed of in the immediate future, but a marked systemic improvement is unlikely and it is imperative that the judiciary look to address systemic problems if we are to make any headway in improving access to justice.

A study of select district courts published by Surya Prakash B.S. and Siddharth Mandrekar Rao in DAKSH’s Justice Frustrated: The Systemic Impact of Delays in Indian Courts showed that increasing the number of judges does not necessarily lead to better court performance.

Their study indicated that new courts and transfer courts (from where cases were transferred to the new courts) were actually worse off when compared to courts that experienced no change.

This points to the fact that there are other factors at play and a mere increase in judge strength does not necessarily translate to speedy justice. There is a need to address larger systemic inefficiencies in areas such as listing, ensuring effective hearings, implementing case flow management and putting in place an effective administrative structure so that judges can maximise their time and effectively focus on adjudication.

With the pandemic continuing to worsen, it is an understandable reaction to laud even placing a bandaid on a gaping wound, but we must equally invest in a proper diagnosis and surgery if we are to enable our justice system to flourish.

Shruthi Naik is a senior research fellow at DAKSH, Bengaluru.